The Grand is the longest river entirely in southern Ontario. It’s not a great continental waterway like the St. Lawrence, but it’s a lot bigger than jumped-up creeks like the Humber or Don (sorry, Toronto!) At about 300 km, it’s a fair bit longer than both the River Ouse in Yorkshire, England and the Mohawk River in upstate New York, two rivers with which it has been historically associated.

The Grand’s watershed – the area of land drained by it and its many tributaries – is an extensive 6,800 sq. km. However, the great population centres of southern Ontario, namely the Golden Horseshoe/Greater Toronto-Hamilton Area, sit outside this drainage basin. Perhaps this is why the Grand’s profile remains relatively low, even in its own province.

The Grand runs along the eastern periphery of the twin cities of Waterloo (pop. 121,000) and Kitchener (257,000) and flows through the centre of Cambridge (138,000) and Brantford (105,000). Otherwise it connects a series of small towns, three of which are among the most attractive in Ontario: Fergus (20,000), Elora (8,000), and Paris (15,000). It has had a long and close relationship with the Six Nations Reserve downstream from Brantford.

The Grand has a handful of major tributaries. From north to south these are: the Conestogo, which joins the Grand north of Waterloo; the Speed and its own tributary the Eramosa, which join the Grand at Cambridge; and the Nith, which joins the Grand at Paris.

The Grand’s origin on the Dundalk Plateau is a mere 40 km from Georgian Bay (Lake Huron) and in its course it approaches within 40 km of Lake Ontario. But instead of debouching into either of these nearby Great Lakes, the Grand takes a long southeasterly route, entering distant Lake Erie at Port Maitland.

(Top) A 1755 map of the Great Lakes by French cartographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellin.

(Bottom) A detail from the above. At left centre is marked the course of “R[ivière] d’Urse ou La Grande Rivière” (“Bear River* or The Big River”) from highlands west of Lake Ontario southeast into Lake Erie. So, the origin of the Grand River’s name was French and why it was so called is plain: the Grand is a big river!

We can infer from the maps above that the northern half of the Grand was unexplored by settlers. That’s because the mapmaker has apparently confused the Grand’s headwaters with those of a “Rivière Inconnue” (an “unknown river,” now the Thames) that flows into Lake St. Clair.

In the maps, a dotted line representing a First Nations portage trail goes between the Grand River near what is now Brantford to the navigable head of Lake Ontario, probably present-day Dundas. About halfway between these points is marked the Seneca village of Quinaouatoua (a.k.a. Tinawatawa), thought to have been located in present-day Ancaster or West Flamborough district. The need for a portage route between Lakes Erie and Ontario is obvious when you recall that the Niagara River directly connecting the two lakes is unnavigable thanks to the world-famous Falls (“Sault de Niagara” on the map).

*Bears have been a very rare sight along the Grand for a long time, so it’s not surprising that this name never caught on.

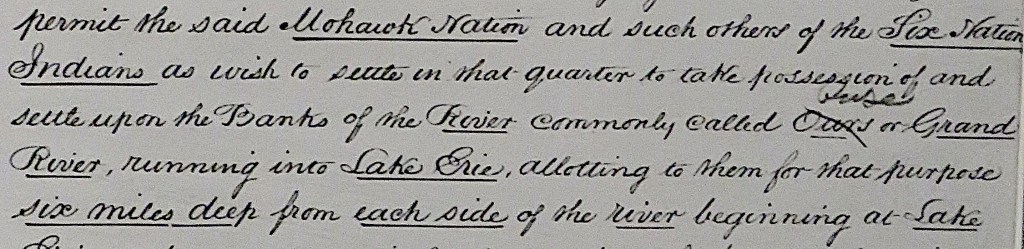

In the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784 – we’ll hear much more about this in due course – our River is referred to as the “Ours or Grand.” But the word “Ours” (the standard spelling of the French word for “bear”) has been struck through and “Ouse” written above. That’s because in 1793 Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, who liked to anglicize place names in Upper Canada but who evidently had a tin ear, decided to rename the Grand the “Ouse” after the river in Yorkshire, England. But “Ouse,” which sounds exactly like “ooze,” is an unflattering name to say the least, and it was “Grand” that stuck. And quite rightly too. The Grand River is … grand!

In this photoblog, I follow the Grand from source to mouth, capturing it in images and text at every season of the year. Unlike my previous photoblogs, this one won’t document a continuous series of hikes. That’s because long stretches of the Grand are on private land and off limits to visitors. I’ll hike sections of riverside trail whenever possible. But where the riverbank is inaccessible, you’ll find me on bridges and at public viewpoints. And as I follow the Grand downstream, I’ll explore the fascinating history of this river and its surrounding settlements.

There is a Grand Valley Trail (GVT), and an official Guidebook to it (above left: 8th edition 2022 depicted) produced by the Grand Valley Trails Association (GVTA). Maps of the GVT are also available as (currently free) apps on Ondago. However, the GVT starts at Belwood, a long way south of the river’s source, and a lot of it is on roads. If completion of the GVT is your goal, plan to do it by combining bike and car rather than on foot. Parking places are identified in the maps in the Guidebook and on the app.

There’s also a guide, Canoeing on the Grand River (above right; 1995 edition depicted) published by the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA). Canoeing and kayaking on the Grand also begin at Belwood. You should note that while stretches of the Grand are ideally suited for boating, paddling, or floating during clement months of the year, there are many dams and weirs, not all of them easily visible or provided with advance warning signs, that must be portaged around. Also, heavy rainstorms can quickly transform the languid summer Grand into a torrent. Seriously: three people were drowned on the Grand in one week in July 2024. The Grand is a big river and should be treated with respect. There’s a list of official safe access points for watercraft on the GVCA website.

“The source of the White Nile, even after centuries of exploration, remains in dispute” (Wikipedia)

So, I’ll start at the source of the Grand. Where is that, exactly?

Google Maps and Google Earth confidently flag the source of the Grand River in a farmer’s field about 370 m northeast of Ontario Highway 10 and about 1.2 km southeast of Dufferin County Road 9 in Melancthon Township, not far from the town of Dundalk.

Wikipedia is vaguer: it gives the Grand’s source as “near Wareham,” a hamlet about 12 km north of Dundalk.

The Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA), which should know, notes merely that “The Grand River starts in the Dufferin Highlands at an elevation of 525 metres (1,722 feet) above sea level.”

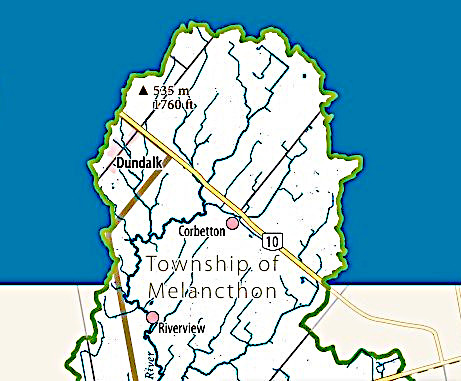

The GVCA provides a detailed online map of the Grand River watershed. The image above is an expanded detail of its northernmost section. It shows that there is no single source of the Grand. Rather a number of rivulets combine until, south of Highway 10, a dominant waterway emerges. Many of these rivulets will be dry much of the year, but will fill during spring thaw or after heavy rainfall.

We humans like clear quantified facts, but Nature isn’t so obliging. Major rivers do not spring into being on one spot, but evolve from multiple factors. So: a river’s “source” and its “length” are always variable and ultimately indeterminable.

Still, I’m determined to capture an image that will serve as my starting point. So I head to Dundalk (pop. 2,800), a small town in Southgate Township in the southeast corner of Grey County, about 125 km by road northeast of Toronto. Dundalk was founded as McDowell’s Corners, then renamed in 1874 for the Irish home town of a prominent resident. Dundalk’s main claim to fame today is that it is the town at the highest elevation above sea level – 526 m/1,726 ft – in southern Ontario …

… not that this dizzying height is at all obvious on the ground. This view of Dundalk across fields makes you think more of flat prairie than of rugged highlands. Nevertheless, Dundalk is on a high plateau on which several rivers originate. These include the Saugeen, Beaver, and Mad Rivers, all of which flow a relatively short distance north into Georgian Bay.

The Grand, however, flows south.

“So this is where the Grand begins. When more drops are added and more threads of water, it flows a bit faster among the plant stems, visible only to the small creatures that live there. These are its first syllables of its dialogue with the land. Very soon the stream begins to make a riverbed, to acquire banks. It grows into a creek big enough so that at its intersection with a road there is a culvert. Other creeks merge with it: it is now part of a watershed” – Marianne Brandis, The Grand River: Dundalk to Lake Erie (2015).

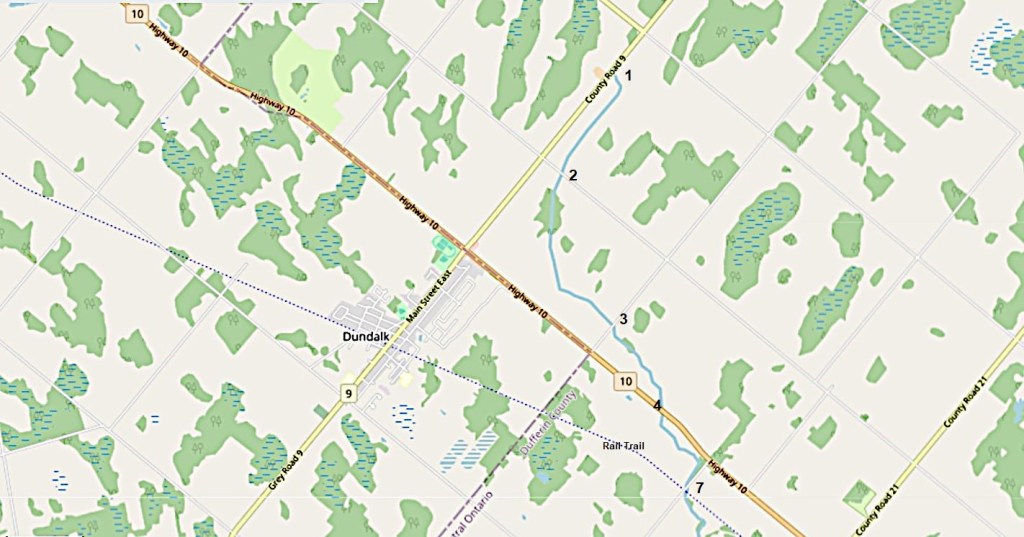

Map 1.

The maps I provide in this photoblog are all reproduced courtesy of OpenStreetMap and its contributors. Numbers along the Grand River on these maps refer to subsequent blog entries with the same numbers.

Unlike Google, OpenStreetMap doesn’t flag “the” source of the Grand. But it does indicate by a blue line that a watercourse it soon identifies as the Grand River starts on the east side of Dufferin County Road 9 about 4.5 km northeast of Dundalk. (East of Highway 10, you’re in Dufferin County.)

1. I didn’t have to trespass on private land to photograph this scene. I merely stopped the car on the east shoulder of County Road 9.

It’s mid-August, and a marshy channel snakes slightly downhill through a cornfield. Its course is defined by cattails and goldenrod, but no water is visible. There’s no culvert under CR 9, nor is there any corresponding channel on the other side of the road. This is my “Source of the Grand River” picture, then. You have to start somewhere!

2. As all the surrounding area is private farmland, I could only follow the course of the embryonic Grand by marking where it crosses public roads. Now I’m on Second Line NE looking northeast (top) and southwest (bottom). The latter image shows a first culvert under the road, but there’s no water visible yet in either direction.

3. Next stop is on 240 Sideroad. There’s a large culvert under this gravel road. This spot is 450 m northwest of its junction with Hwy 10, we’re looking south, and that’s Dundalk on the horizon at left. There’s still no water visible in the marshy course of the riverbed, but there’s plenty of Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum) in bloom. This moisture-loving purple flower came to define for me the earliest stages of the Grand in midsummer.

4. The Grand then goes under the first bridge of the more than 600 in its watershed, the one carrying Highway 10 southeast toward Toronto. Lo and behold, the view north (top) gives us a glimpse of running water in an already well-defined channel. The Grand River is born!

The view south from the other side of Hwy 10 (bottom) shows water flowing toward the next culvert under 250 Sideroad. The course of the stream or brook destined to become the Grand River is now pronounced, with purple Joe-Pye weed and not-quite-in-bloom goldenrod lining its banks.

5. This is a peaceful agricultural area, the silence broken only by a harvesting operation.

6. In the distance, the windmills of Melancthon. There are 167 wind turbines in the Township, each 80 m tall and together generating over 200 megawatts of electricity.

7. A rusty old railway bridge crosses the infant Grand at right angles to 250 Sideroad …

… a bridge that used to carry the Toronto, Grey and Bruce (TG&B) Railway from Toronto via Dundalk to Owen Sound. The line was completed in 1873, and its existence explains why Dundalk is near, but not on, Highway 10. The village of McDowell’s Corners was literally moved closer to the new station that served it, then it was renamed Dundalk. The TG&B was taken over by Canadian Pacific in 1883, and service was discontinued in 1970. Much of the line’s northern section survives as a rail trail. North of Dundalk it’s called the Grey County CP Rail Trail, running 77 km to Owen Sound. South of Dundalk, it’s the Dufferin Rail Trail, and runs 38 km to Shelburne.

The view northeast from the former railroad bridge. That truck is going southwest along 250 Sideroad. The Grand is now a well-established creek with the brownish colour that it’ll retain even when it has become a mature river.

Map 2.

8. Two views from the bridge on 250 Sideroad: looking west (top) and east (bottom). We’re in Melancthon Township, one of the most rural and thinly populated municipalities in southern Ontario. The Township was named for the German Protestant theologian Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), presumably for a similar reason that the nearby Luther Marsh was named: to commemorate the two leading figures of the Lutheran Reformation. Phil’s surname is spelled with only one “h” hereabouts and is pronounced Mel-ank-ton.

And yes, that’s a vast, neatly mowed lawn sweeping down to the bank of the baby Grand in the top image.

9. From the bridge on Second Line SW, I catch another riverside lawn in the act of being mown. The North American lawn fetish, and its accomplice the riding mower, has infected even this deeply rural area, miles from any suburb.

10. The view from the bridge on Fourth Line SW, looking northeast (top) and southwest (bottom). The baby Grand sometimes broadens briefly as it passes under bridges. That’s probably because bridge abutments break up and disperse its flow during times of high water, widening its banks.

11. We enter the hamlet of Riverview, “Where the Grand becomes a River,” on 260 Sideroad.

12. Welcome to Riverview!

13. The Grand viewed from the bridge on 260 Sideroad in Riverview. Has it really now graduated to River status or is it still a wet-behind-the-ears creek? It seems to me that, where there’s no bridge, you wade, or use stepping stones, or funambulate along a fallen tree trunk to cross a creek. To cross a river, you have to swim. Here, thanks to that strip of concrete, you don’t even have to get your feet wet.

14. Great clumps of purple knapweed adorn the banks of the Grand in Riverview. It’s considered an invasive, highly undesirable plant in cropped fields, but here at the heart of this tiny community it’s rather pretty.

15. It may still be only a creek, but here in Riverview the Grand already exhibits the qualities that make a waterway resemble a living thing, perpetually changing, reflecting the unceasing unidirectional flow of time.

In Plato’s dialogue Cratylus, Sophocles refers to the central idea of an earlier Greek philosopher: “Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice into the same river.”

You can’t photograph the same river twice, either. I took the above two images a few seconds apart from exactly the same spot in Riverview.