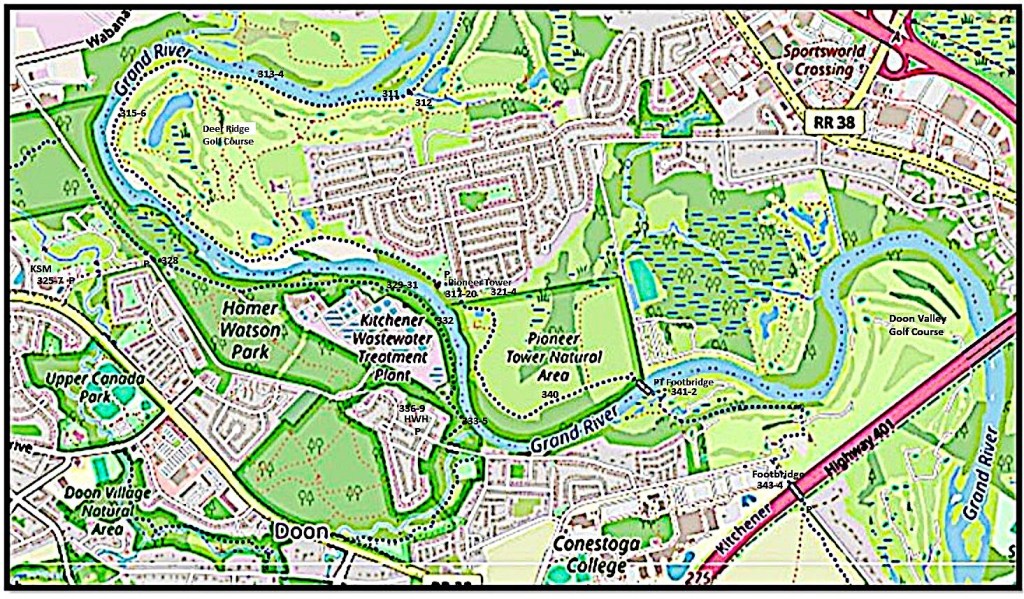

Map 26. On the east bank: the Walter Bean Grand River Trail (blue dots) from Deer Ridge Golf Course via the Pioneer Tower and the Pioneer Footbridge (PF) over the Grand as far as the Kitchener City limit at the footbridge over Highway 401.

On the west bank: the Trans-Canada Trail (blue dots) from the Ken Seiling Museum (KSM) via Homer Watson Park and Homer Watson House and Gallery (HWH) to Schneider Creek.

The southbound trails merge at the Highway 401 footbridge, after which the combined trail continues on the west bank.

311. It’s a beautiful fall day on the Walter Bean Grand River Trail (WBGRT) near Grand View Woods as I prepare to round the inner bank of the oxbow that’s occupied chiefly by …

312. … the idyllic expanse of Deer Ridge Golf Course. That’s the 16th hole in the foreground. Weird that there isn’t a golfer in sight on such a fine day.

313. My eye is caught by movement on the opposite shore …

314. … it’s a turkey vulture picking over the remains of a large fish, probably a salmon.

315. Today is as close to peak fall colour as it ever gets …

316. … and reflecting those colours, the Grand does its best Monet impression.

317. The Waterloo Pioneers Memorial Tower. P at Kuntz Park.

The Tower, 18.9 m tall, is built of random-coursed fieldstone and was dedicated on 23 August 1926. It commemorates not just Joseph Schörg and Samuel Betzner (see #319 below), but the many later Mennonite arrivals from Pennsylvania, and all the German-speaking immigrants who settled in this area later still and helped to develop it. The erection of the Tower after WWI was intended to heal the wounds of anti-German feeling, and affirm the self-worth of the large local German-speaking community and its loyalty to Canada. The Tower’s architect was William A. Langton of Toronto, who designed its Swiss-style copper spire over a hexagonal platform. “If … you stand on the platform directly over the portal with your back square to the opposite angle of the hexagon [there’s a] true air line direct from this tower to Franklin County, Pennsylvania” (Liebbrandt, Little Paradise 211).

As for climbing the Tower, from 2015 you had to apply to Parks Canada to have it specially opened for you. Currently the Parks Canada website states bluntly: “Waterloo Pioneers Memorial Tower is not open for visitation at this time.” A pity. I bet the view is tremendous.

318. The Pioneer Tower stands on the “historical ridge” in the vicinity of which the first three Pennsylvania Mennonites in the area settled. This aged plaque affixed to the side of the Tower names them. But why did they come here?

The Mennonites were persecuted, often severely, in their Swiss, German, and Dutch homelands for their beliefs in adult baptism, pacifism, refusal to swear oaths, and non-resistance. Many of them eventually fled to North America, where as accomplished farmers they found ample tracts of arable land. The first group of them had landed at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1683 and founded Germantown, now a suburb of that city. Pennsylvania itself had been founded by William Penn, a Quaker, only one year earlier as a colony where, very unusually for that time, religious toleration was practiced.

By 1709 hordes of German-speaking Protestant refugees from persecution, war, and famine in their European homelands had arrived in London, England. Queen Anne encouraged 3,000 of them to emigrate to Pennsylvania, where they would enjoy freedom of worship. But later that century, as revolutionary fervour gripped the American colonies, the Mennonites, always keen to avoid violence, realized that if they stayed put they’d be liable for military service. So many of them chose the British Crown – then worn by Hanoverians, a German dynasty – over the new American Republic, and this meant removing themselves to British North America. Upper Canada (now Ontario) was very thinly settled, and they quickly recognized the agricultural possibilities of the Grand River valley in the Waterloo Region.*

*For how the Mennonites acquired land in Block 2 of the Haldimand Tract, please see #250 above.

319. The Tower’s weather vane in the form of a Conestoga wagon celebrates the vehicles the Mennonites used to make the long trek from Pennsylvania. How did the first two get here at a time when there were no good roads at all in Upper Canada? The answer is ultimately speculative, though the variables are limited.

Joseph Schörg (later Sherk), Samuel Betzner, Jr. and their families left their farms near Chambersburg, Franklin County, in southern Pennsylvania in the fall of 1799. “Their route, very probably, was to Harrisburg, up the Susquehanna to Northumberland, then, by the west fork, on to Williamsport, from where an old road is shown on the maps leading northerly across the [Allegheny] mountains to Elmira or Bath” (Breithaupt). From there they would have had to run the gauntlet of upstate New Yorkers who had almost certainly heard that these Mennonite Americans were planning to move to British North America. The New Yorkers would have considered them traitors, like their predecessor Empire Loyalists who had left the USA during and immediately after the Revolutionary War.

The Mennonites would have crossed the Niagara River by the flat-bottomed scow ferry at Black Rock north of Buffalo, and wintered in the Niagara Peninsula. There was already a small community of Mennonites settled at “The Twenty,” namely Twenty Mile Creek near Vineland, west of what is now St. Catherines.

In the spring of 1800 Schörg and Betzner probably first took the Iroquois Trail along the lakeshore to the head of Lake Ontario at Cootes Paradise (now Dundas). Their wagons are likely to have been pulled by oxen over this leg, as these animals are stronger than horses and more suited to very rough terrain. From there they would have taken the new but still rough Dundas Street – a.k.a. the Governor’s Road, opened 1793 – east to the Grand River at what is now Paris. Then they would have followed First Nations trails on the east bank upstream. This journey of over 650 km / 400 miles would have taken about five weeks’ travel time, not including stops.

Later immigrants would take the more direct Beverly Road from Dundas – now Highway 8 – towards Waterloo, though this involved negotiating the notorious Beverly Swamp. In these early days this route was only passable by heavy wagons in winter, when the Swamp was frozen over.

320. A child’s gravestone in the Doon Pioneer Cemetery near the foot of the Tower. Here’s a translation of the inscription: “Maria Schörg died on 8 December 1836. Her age was 3 years 6 months 14 days.”

According to the genealogical site Waterloo Regional Generations, 3½-year-old Mary Shirk [sic] died of scarlet fever. Her 5-year-old sister and 2-year-old brother had died of the same ailment four days earlier. They were the second, third, and fourth children of Rev. David and Elizabeth (née Betzner) Sherk, who would have 14 children in all. Rev. David was the fifth son of the pioneers Joseph and Elizabeth Schoerg (see #321 below). Both Mary’s parents lived into their 80s and most of their children survived into adulthood.

The language of the Mennonite settlers, here inscribed on the gravestone, is commonly known as “Pennsylvania Dutch.” This is misleading: “Dutch” in this context does not refer to the Netherlands, but is an anglicization of “Deitsch,” that is, the word in the settlers’ language that means “German” and is equivalent to modern standard German Deutsch. Pennsylvania Dutch, which is still spoken in the USA and Canada by about 300,000 people, is a descendant of the combination of the various German dialects spoken by late 17th and early 18th century immigrants to North America from German-speaking Europe.

321. Joseph Schoerg Crescent is the name of the road just east of the Pioneer Tower. Here the City of Kitchener has made a reasonable attempt to commemorate that this land was once occupied by two of the first three white settler families in the interior of Upper Canada.

Joseph Schörg (1769-1855) and his wife Elizabeth (née Betzner, b. 1773), had five children when they arrived here in 1800. They will have camped here on top of the high east bank of the Grand and built their log cabin out of timber they hewed on the spot. Their sixth child, David, was born the following year, the first non-indigenous child born in Waterloo County. (They would have 10 children in all.)

However, the Schörg farmstead, at 200 Joseph Schoerg Crescent, was fenced off and under major reconstruction when I visited. So it’s the already reconstructed buildings on the adjacent Betzner lot that command attention. This lot was first occupied by Samuel Betzner senior (1738-1813), the third settler in the area. Father-in-law to Joseph Schörg, Betzner Sr. came here later in 1800 to be close to his son Samuel Jr., whose homestead was three miles south of here on the west bank of the Grand.

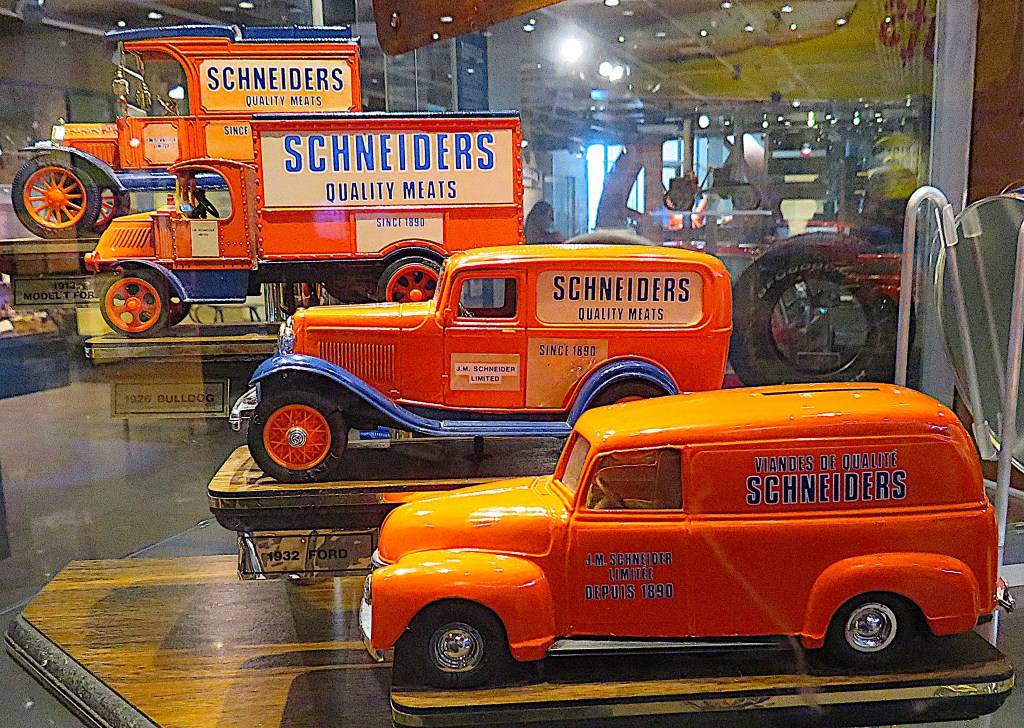

Above is the foundation of the Betzner bank barn,* built ca. 1830, destroyed by fire, then rebuilt over this fieldstone foundation with corners strengthened by limestone blocks, in 1910.

*A bank barn is built on the side of a slope, so that there are entrances at at least two different levels.

322. The interior of the barn foundation. The contemporary world intrudes in the shape of new housing in the large, affluent Pioneer Tower West subdivision of Kitchener that occupies much of this part of the east bank of the Grand.

323. No. 300, on the south side of Joseph Schoerg Crescent, is a classic Mennonite Georgian-style former farmhouse, originally built by John Betzner (1783-1852), son of Samuel Sr., in about 1830, though it’s been much updated recently. Simple and classic in its proportions, it puts the recent domestic architecture around it to shame. It was recently sold for around $3.5 million.

324. Next to it is the Betzner Driveshed, an outbuilding originally used to shelter farm equipment and visitors’ horses. These days it’s been converted to a guest suite by owners of No. 300 next door.

325. Let’s move to the west bank. The exterior of the Ken Seiling* Waterloo Regional Museum at 10 Huron Road in the Doon area of Kitchener. The Museum shares its site with Doon Heritage Village, though the latter is currently closed for renovation. The Museum has ample free P. Open Wednesdays to Sundays, 11 am – 4 pm. Adult admission $12 with discounts for families, seniors, students, and children.

The Museum is 500 m west of the Grand near the east end of Huron Road. This was the historic road from Guelph to Goderich that was opened up in 1827 to enable settlement of the lands between.

*Ken Seiling was the long-serving chair of the Regional Municipality of Waterloo (1985-2018). Among other achievements, he was instrumental in developing the ION LRT system.

326. Outside the Museum there’s a preserved “Petersburg Station” formerly on the Grand Trunk Railway. On the track is Canadian Pacific Railway locomotive 894, built in 1911 and recently restored.

327. The interior of the Museum focuses on local businesses, one in particular. The meat-packing company Schneiders was founded by John Metz Schneider in 1890. Schneider, whose heritage was German, was born in Berlin (now Kitchener). He began by selling homemade sausages from his house on Courtland Avenue in Berlin. By 1965 Schneiders were selling 250 different meat products. A giant Schneiders sign, the so-called “Wiener Beacon,” featuring the blonde “Dutch Girl” logo and the slogan “Famous for Quality” still greets westbound motorists on Highway 401 as they approach Waterloo Region. The “Dutch Girl” avoids the negative connotations of “German” that accumulated during the first half of the twentieth century. The logo derives of course from the common misunderstanding of “Pennsylvania Dutch.” Schneiders was bought out by the Canadian multinational meat-packers Maple Leaf Foods Inc. in 2003. They closed down the Kitchener plant in 2015 with the loss of 1,500 jobs and moved it to Hamilton.

328. There’s a pleasant section of the Trans-Canada Trail (TCT) that follows the west bank of the Grand south from Huron Road. P at Wilson Avenue at the east end of Huron Road.

This area used to be called Cressman’s Woods but since 1943 has been known as Homer Watson Park, in memory of the artist (see #336 below) behind the campaign to preserve the area.

329. Here’s a tableau I’d been hoping to capture on film for some time. A young white-tailed deer comes down to the river’s edge on the opposite bank and drinks.

330. Have you got your ducks in a row?

These female mallards are swimming in almost single file. They adopt this quasi-military behaviour defensively, as it allows them to watch for predators in unfamiliar territory. The front duck looks ahead, while each of the ducks behind has a clear line of sight from side to side. This lining-up is reminiscent of what they did when, as ducklings, their mother would take them swimming for the first time.

331. The spire of the Pioneer Tower from the west bank.

332. This is giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), a truly nasty denizen of the Grand riverbanks. It can grow as tall as 5.5 m (this one is over 2 m). It’s an import from Eurasia, probably brought over by gardeners who thought it made an interesting curiosity. It was sold in nurseries in Ontario as late as 2005. It looks like a giant Queen Anne’s lace, and that’s because it’s related as a fellow member of the Umbelliferae, which include such innocuous vegetables as carrots and parsley.

Giant hogweed’s sap is phototoxic and causes phytophotodermatitis in humans. Phototoxicity refers to the way that the chemicals in the sap, when they encounter human skin, cause a response to light as if it were a poison. The resulting phytophotodermatitis is a very painful skin irritation, with blistering, severe burns, and scarring, all of which may last weeks. And if that’s not bad enough, post-inflammatory red pigmentation on the affected skin can last for years. Don’t even brush against these monsters, as the consequences can be far worse than poison ivy! If you do make contact with a giant hogweed, cover the affected skin with sunscreen as soon as possible to cut down on light absorption.

333. A quiet backwater near Schneider’s Creek

334. The Lower Doon Mill ruins, Schneider Creek, on the Trans-Canada Trail.

Though this area was first settled by Mennonite farmers, the village of Doon was founded by Scottish immigrants who arrived here after 1830. In 1834 Adam Ferrie (see #336 below) named his settlement Doon Mills, for the River Doon in Ayrshire, Scotland. By 1852, the village included a grist mill, sawmill, smithy, tavern, hotel, general store, tailor shop, shoemaker, wainwright, and workers’ houses. In 1898, a fire broke out and destroyed the mill. The roof was then replaced, and businesses making glue, cider, and scissors occupied the mill buildings. But in 1922 another fire broke out and left the buildings damaged beyond repair. Most of the mill buildings were bulldozed in 1981, but Kitchener spent $5,000 to preserve a small part of the ruins. Doon is now a southern suburb of Kitchener.

335. A spotted sandpiper forages under Old Mill Road Bridge over Schneider Creek.

336. The Homer Watson House and Gallery, 1754 Old Mill Rd., Doon. The house, which stands about 250 m from the west bank of the Grand, was built, perhaps in 1834 though more probably in 1850, by one of the Ferrie family who founded Doon. It was bought by the artist Homer Watson in 1883 and he lived in it until his death. Thereafter it was used for many years as an art school. The house was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1980. The City of Kitchener purchased the property in 1981 and it’s now a gallery displaying both its collection of Watson’s works and circulating exhibitions.

Open every day except Monday, admission by donation. Free P on the street.

Homer Ransford Watson (1855-1936), who was born and died in Doon, was a pioneering Canadian landscape painter many of whose best paintings contain local river motifs. If there is a Master of the Grand River, Watson is he. Largely self-taught, he met other artists only after he moved briefly to Toronto in 1874. He was inspired by the English landscapist John Constable, and the painters of both the French Barbizon School and the American Hudson River School. These artists painted local landscapes that they knew intimately, rather than ones based on classical or imaginary subjects.

Watson married in 1881 just as his fame grew, and thanks to his sales he and his wife Roxanna were able in 1883 to buy the Ferrie house in Doon. It was his principal residence until his death, though he travelled widely during his long life.

337. The Gallery houses a reconstruction of Watson’s studio, built as an extension to the house in 1893. The names of artists that Watson considered kindred spirits are in the frieze that he himself designed: [John] Constable, [Camille] Corot, Claude [Lorrain].

Watson was very popular in his lifetime. His fortune was made when John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, the Governor General of Canada from 1878-83, bought his painting, “The Pioneer Mill” for $300 in 1880 as a gift for his mother-in-law Queen Victoria. The Marquess bought a second painting for the Queen, “The Last Day of the Drought,” the following year, and both paintings remain in the Royal Collection. In 1882 rising celebrity Oscar Wilde called Watson “the Canadian Constable” and commissioned a work for his own collection. Watson and Edmund Morris co-founded the Canadian Art Club in 1907, and Watson served as president until 1913. He was also president of the Royal Canadian Academy, 1918–21.

338. “I obeyed then certain desires which altogether possessed me into fixing in some palpable degree the infinite beauties that emanate from the great mystery of the sky and land” (Silcox).

“Grand River Valley” (oil on board, ca. 1880). A pastoral scene that captures the peaceful spirit of the Grand in summer. It’s appealing, if slightly idealized and sentimental, the kind of scene that would make a good jigsaw puzzle or greetings card.

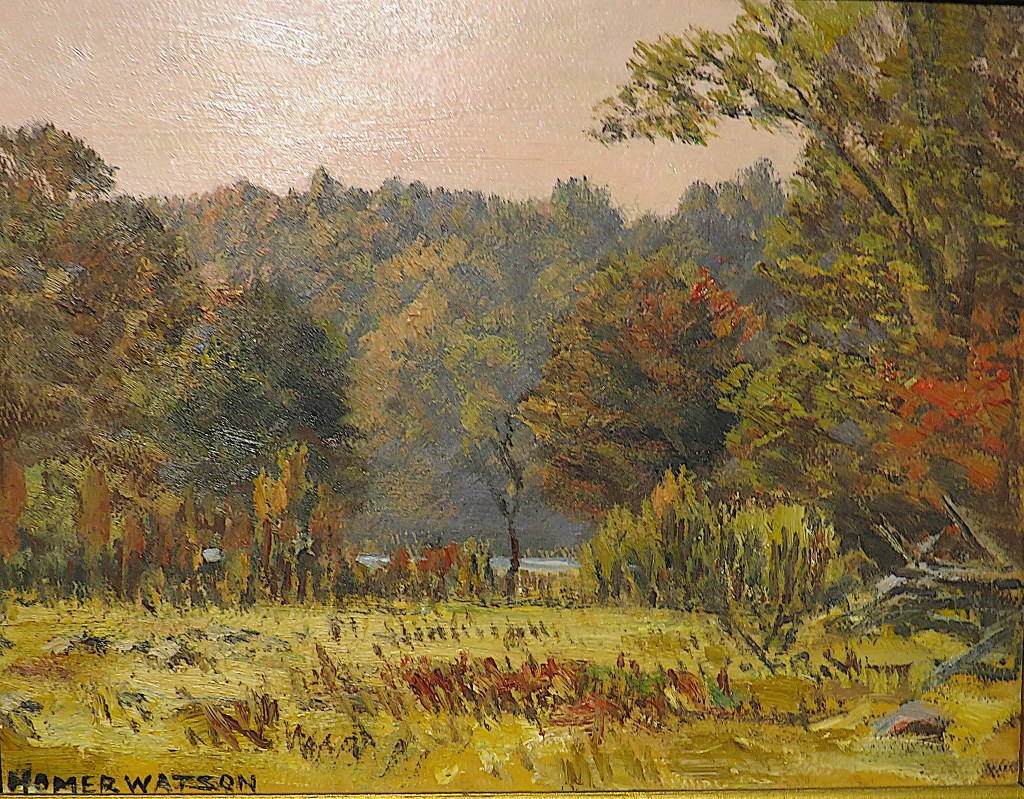

339. “Autumn Landscape” (oil on board, ca. 1930). This is surely a depiction of the Grand River glimpsed through trees in early fall. There’s a part of a traditional split-rail fence at bottom right. The scene could have been painted in any one of a hundred places along the Grand in the Waterloo Region.

Some consider Watson’s later works weak, especially when compared to the raw and bold expressionistic colours of the Group of Seven, who had risen to prominence during the 1920s. I disagree. This painting is much more impressionistic, subtle, and “modern” than the one at #338 above painted fifty years earlier. For me, no painting better captures the elusive beauty of the Grand River and its valley.

340. Back to the east bank. Densely overgrown river flats in the Pioneer Tower Natural Area.

341. The pedestrian footbridge over the Grand on the WBGRT about 1.5 km southeast of the Tower.

342. Two views from the footbridge above.

(Top) The Grand downstream. Neither bank is publicly accessible until after Blair Bridge.

(Bottom) A gentleman and his dog relax in the sun on a riverside lawn on the east bank.

343. The footbridge over Highway 401 at the north end of Morningside Drive (P). That’s where the WBGRT and TCT meet. They’ll continue together until the WBGRT ends at its southern trailhead in Cambridge (see Part 12).

344. Ontario Highway 401 looking east from the footbridge. Hwy 401 runs 828 km / 514 miles from Windsor in the west to the Quebec border in the east. This stretch forms the boundary between the cities of Kitchener (on the left) and Cambridge (on the right). The 401, notorious as the busiest highway in North America as it passes through Toronto, is currently being widened here from six to ten lanes. The 401, full name the Macdonald-Cartier Freeway but known everywhere locally as the four-oh-one, crosses the Grand at that low point in the image above, about 1 km away. The whole of the west bank under the bridge is the private territory of the Doon Valley Golf Club. Here’s hoping that in the future the Doon Valley Club allows hikers on the WBGRT access to their extensive stretch of riverbank, as the Deer Ridge Club has done.