345. Galt City Hall (1857-58) and part of the new Cambridge City Hall (2008) at right angles to it.

Cambridge (pop. about 140,000), the third and southernmost of the K-W-C Tri-Cities, is a recent creation. Unlike Kitchener and Waterloo, Cambridge is itself an amalgam of preexisting municipalities. Before 1973, there was the city of Galt (incorporated 1915) through whose centre the Grand River flows; the town of Preston north of Galt on the east bank of the Grand; the village of Hespeler, northeast of Preston on the Speed River; and the village of Blair, which had itself been absorbed by Preston in 1969, west of Galt on the Grand. In 1973, these very different settlements, each with its own proud history, were amalgamated by the province of Ontario and told to choose a new name for the combination. “Cambridge,” a name associated with early mills in Preston, was narrowly and unenthusiastically chosen after a plebiscite.

The centre of Galt is considered the downtown of Cambridge as a whole, and the Grand flows right through the middle of it. So Cambridge is one of only two relatively large cities – the other is Brantford – that are truly on the Grand River. Following the practice of many of the residents, I’ll use the names of the former settlements to identify different areas of Cambridge.

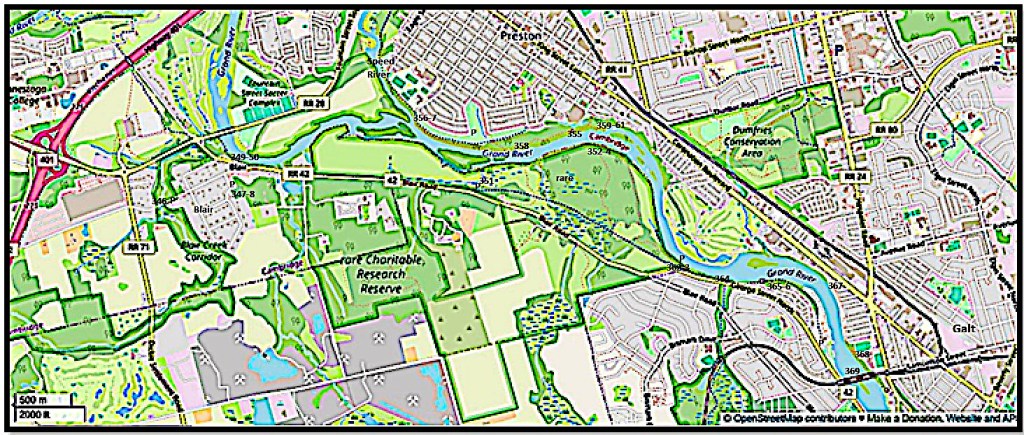

Map 27. From the Highway 401 footbridge to the CPR Rail Viaduct.

On the west bank of the Grand, the combined Walter Bean Grand River Trail (WBGRT) / Trans-Canada Trail (TCT) takes us through the village of Blair and the rare Charitable Research Reserve, the latter of which has a number of named trails of its own. The WBGRT ends at its southern trailhead on the west bank, but then the Grand Trunk Trail (GTT) continues to its own trailhead in Riverbluffs Park.

On the east bank there is more limited river access. It starts on the east side of the Grand’s confluence with the Speed River, where a Linear Trail takes us though part of Preston.

Once over the 401 footbridge you enter the city of Cambridge, but the rare Reserve is in an enclave of the Township of North Dumfries. You reenter Cambridge at Devil’s Creek. The east bank is entirely in the city of Cambridge. Parking places are marked P.

346. Oh! the wasted hours of life, that have swiftly drifted by,

Alas! the good we might have done, all gone without a sigh;

Love that we might once have saved by a single kindly word,

Thoughts conceived, but ne’er expressed, perishing unpenned, unheard.

Oh! take the lesson to thy soul, forever clasp it fast –

“The mill will never grind again with water that is past.”

– from Sarah Doudney (1841-1926), “The Lesson of the Water Mill” (1864)

First, let’s visit a couple of off-trail sites in Blair.

The sheave tower on Blair Creek is worth a short side trip. P roadside at 90 Old Mill Road then walk along a short trail.

This is possibly the last existing trace in Ontario of an ingenious 1876 technology. A wooden tower 9.4 m / 31 ft high was built by Allan Bowman to supplement the 25 horsepower of the millwheel at his four-storey Blair Carlisle Grist Mill a little way upstream. He diverted water from Blair Creek – which had already turned his millwheel – under the tower, where a turbine turned a shaft connected to the sheave, a wheel with a grooved rim like a large pulley, at the top of the tower. The sheave carried cable that ran back 73 m / 240 ft across the road to the mill. The result was the addition of another 15 hp to the grinding ability of the millstones. So the old proverb “The mill will never grind again with water that is past,” the refrain of Sarah Doudney’s once well-known poem, was proven incorrect!

A fire in 1928 destroyed the original mill. The rebuilt lower-rise structure, now owned privately, still stands on the south side of Old Mill Road. In the 1930s the sheave tower was briefly turned into a small hydroelectricity generating station, until the mill ceased operation. In 2000 the tower was restored and unveiled to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the area’s settlement (see #319 above). However, when I first visited in summer the site was overgrown and looked abandoned, and the information board was barely legible. A pity, as the location cries out for a clear explanation of how the sheave setup worked. The above photo was taken in early spring.

347. Old Blair Memorial Cemetery is off Ashton Street, on a rise about 250 m south of the Grand. P roadside.

This 1970 memorial cairn commemorates the first person, a child, to be buried here. His original gravestone has been inserted into the foot of the cairn. It reads, “Erected to the memory of John Bricker, who died the 10th of March 1804, aged 8 years, 4 months and 7 Days.” John Bricker was possibly the first non-aboriginal family member to be formally buried in Waterloo Region. As the Conestoga wagon on the plaque suggests, John was born in Pennsylvania in October 1795, the second son of John and Anna (née Erb) Bricker, Pennsylvania Mennonites, who’d have twelve children, all but two of whom would survive into adulthood.

The village of Blair developed around the mills founded by the Bowman family in 1830. The early village had a variety of names, but was finally named Blair in 1858 for one of the sons of Adam Fergusson, the founder of Fergus (see #121 above).

348. A dark-eyed junco perches on a gravestone in Old Blair Memorial Cemetery. Another name for the junco, a close relative of the sparrow, is “snowbird.” That’s because this bird seems to bring the first snows to southern Canada when it arrives from more northerly latitudes in early winter. It then stays until the snow melts in spring. Now, of course, “snowbirds” refer to Canadians who flock to the southern US to escape the cold winter weather. It must surely have been this human behaviour, in a sense the exact opposite of the avian, that inspired Gene MacLellan to write the song that became a major hit for Anne Murray in 1969.

349. Blair Bridge (1957) from downstream on the short riverside Blair Trail, technically part of the TCT. There was a covered bridge near this spot until 1857.

Though Blair has twice been amalgamated with larger municipalities, it remains village-like, separated from Preston by the river, and from Galt by the rare Reserve.

350. The Grand downstream from Blair Bridge is broad but shallow in summer. These canoeists have run aground and need a helping hand to get them free.

351. We’ve now entered the rare Reserve, to be welcomed by this bald eagle statue. P off Blair Road.

So what is rare (lower case preferred)? To quote its website, it’s “a community-driven urban land trust and environmental research institute protecting over 1,500 acres of ecologically significant lands across eight properties in Waterloo Region and Wellington County,” with conservation as its priority. More specifically, this part of rare was a plot gifted by the Wilks family, owners of a stagecoach inn, to the University of Guelph in 1973 for the purpose of agricultural research. The plot was later bought by a community-based organization aiming to conserve it. In 2004 this organization christened itself the rare Charitable Research Reserve, and now runs children’s eco camps, field trips, and other school and community programs stressing conservation.

rare is located near the centre of the Grand Valley, so we are about halfway in our journey down the Grand from Dundalk to Lake Erie!

352. Once east of the river flats traversed by rare’s Osprey Tower Trail, the terrain becomes forested and rocky. The 2 km River Trail runs beneath outcrops of upper middle Silurian Guelph Formation dolostone, a magnesium-rich limestone 420 million years old. It’s the same capstone that’s found on the Niagara Escarpment in this area.

353. Now this is pretty unusual terrain for the Grand River valley. It’s an alvar, that is, a place where the bedrock is so close to the surface – in places it can be entirely exposed as a flat pavement – that only very hardy, drought-tolerant and shade-intolerant vegetation can grow on it. The word alvar is Swedish, from the Stora Alvaret (the Great Alvar), the world’s biggest, on the Baltic island of Öland. About half the alvars in North America are in the Great Lakes region of Ontario. This one is quite small: the 280 m Alvar Trail traverses it.

354. Young canoeists gather under the west bank of the Grand in rare. You can’t see it from here, but the riverbank is sheer and rocky, with exposed dolostone. See #359 below.

355. So what are these young people in waders doing? Are they checking for the spread of invasive molluscs such as the zebra mussel? Are they involved in a river health workshop just a few metres from the Preston Wastewater Treatment Plant? Or are they monitoring the habitats of endangered amphibians like the northern dusky salamander?

Here’s a thought … why don’t you ask them?

Because they’re on the east bank of the Grand, while I’m across the river in rare over 100 m away. That’s the zoom lens for you.

356. Time to check out the riverbank on the other, Preston side.

357. At this point, known as Settler’s Fork, the Speed River (entering from right), a major tributary of the Grand, joins our River. The Speed comes in from Guelph, where it was joined by the Eramosa, and the combined stream, retaining the name Speed, then flows through the Hespeler part of Cambridge. The Mill Run Trail follows the west bank of the Speed as far as King Street East (Highway 8) in Preston, then the Bob McMullen Linear Trail takes over, following the east bank of the Speed and then the east bank of the Grand. There’s a linear park on this bank of the Grand, and you can take either the paved trail up on the bank, or the less frequented but more scenic riverside gravel trail as far as Bishop Street in Preston. P roadside on Rose Street, Preston.

The Pennsylvania Mennonite John Erb built a sawmill and grist mill just up the Speed from the confluence in 1806-07. It was on the so-called Great Road – now King Street East – from Dundas to Waterloo. A small settlement, Cambridge Mills, grew up surrounding the mills, and this is what eventually gave amalgamated Cambridge its name. After Erb’s death, William Scollick surveyed the settlement and gave it the name of his home town, Preston in Lancashire, England. The site of Erb’s grist mill is still occupied by a flour milling operation.

358. The Grand, swollen by waters from the Speed/Eramosa in early spring, seems a mighty river now. It’s about 120 m from here to the rare river flats on the other side.

359. What you can’t see on the rare side is this sheer rocky bank of the Grand as it makes a 90 degree turn south towards central Galt. This dolomite is rough, crystalline, cellular, and cream-coloured, with many cavities.

360. The gravel path here on the east bank has been partially washed out. It must have been inundated when the Grand reached its maximum flow during the late winter thaw.

361. The Linear Trail ends below the Preston Wastewater Treatment Plant. Farther downstream there’s a brief section of rocky cliff here on the east bank too.

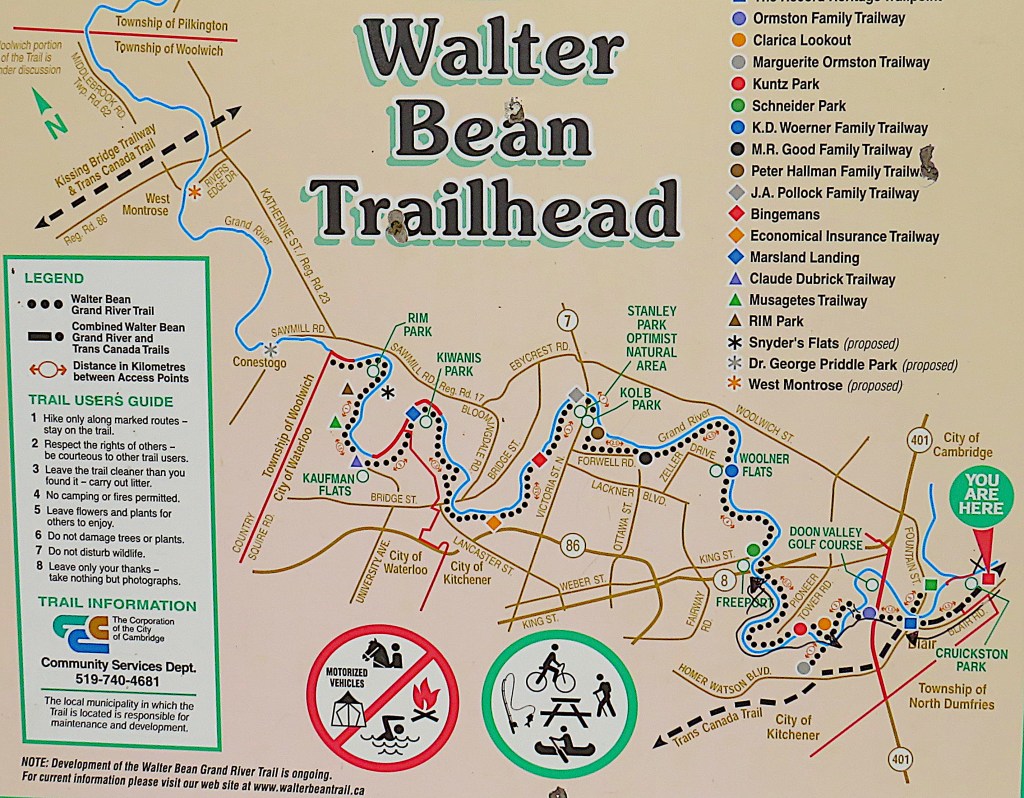

362. The WBGRT, which we have followed for much of its 76 km length (see #258 above for its northern trailhead), ends about 3 km west of downtown Galt. There’s a free P at the Trailhead just off George Street North.

363. The Grand Trunk Trail continues southbound. It’s a 10.5 km rail trail along the former Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) (1871) between Galt and Berlin (now Kitchener). The GTR, once the dominant rail network in Canada, went bankrupt and was absorbed by Canadian National Railway in 1923. Its inability to compete with other North American lines in the early twentieth century was not helped by its having its HQ in London, England, by its initial failure to adopt standard North American gauge, by the death of its president in the Titanic disaster of 1912, and by the enormous cost of trying belatedly to complete a transcontinental system.

364. Devil’s Creek is the boundary between the Township of North Dumfries and the city of Cambridge. This coldwater creek supposedly got its name from smoke coming from a cave in the riverside bluff nearby. But any place name that mentions the Devil is likely to be apotropaic – that is, to have the supposed power to deflect evil. Local parents undoubtedly embroidered a scary legend from a smoky cave to stop children from getting too close to the bluff 12 m high over which the creek abruptly falls into the Grand. Unfortunately there isn’t a good view of this waterfall from here on the west side of the Grand. The tunnel beneath George Street North, which also carries the creek before its final plunge, enables you to access the 1.6 km trail along the Devil’s Creek Corridor that runs from here into West Cambridge.

365. As the GTT rejoins the riverbank there’s a viewing platform that gives a good view of the river upstream. On the opposite bank is the golf course of Galt Country Club. Landside, you find yourself facing an exposed cross-section of dolomite bluff with an information board to hand …

366. … about the fossils embedded in the rock. These are Megalomoideae canadenses, i.e., large, heart-shaped Silurian clams. No, the fossils are not the white patches; those are lichen. The fossils are the same colour as the surrounding rock, so you have to look carefully to make them out. And they don’t look like what you’d expect of clams, as their shells were dissolved by dolomitization. That is, as magnesium from sea water turned limestone into harder, more crystalline dolostone, the clams’ shells along with most smaller fossils were destroyed. What remain are casts, in mud turned to rock, that preserve the shape of the interior clams. Each is about the same size as a beef heart.

In the Silurian period this area was in a huge depression, the Michigan Basin, that was covered by a warm sea. In it reefs were formed by marine creatures. The dolostone, about 40 m deep here, is made of the remains of creatures such as these clams. The fossils are about 420 million years old, so they are 350 million years older than such familiar dinosaurs as T. Rex.

367. Riverside houses in East Galt, perched on the steep east bank of the Grand. Several of these houses have long, elaborate staircases down to boat launches on the river. The long, low building whose roof is visible behind the houses in the top picture is the Cambridge HQ of BWXT Canada, who build nuclear-powered steam generators.

368. The Galt Collegiate Institute and Vocational School on the east bank. This began life as the all-boys Galt Grammar School in 1852. It was renamed the Collegiate Institute in 1872 and became co-educational in 1881. It’s one of the oldest secondary schools in Ontario.

369. (Top) The Grand River Viaduct, built c. 1880 for the Credit Valley Railway, and now part of the CPR system. It’s a steel deck truss bridge 313.6 m long on five piers over the Grand, just north of central Galt.

(Bottom) Freight trains still run, seemingly precariously, along its top deck.