Map 40. This shows Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in relation to the Grand River and surrounding communities. The Grand forms the northern boundary of the Reserve, except for a small enclave north of the river. The marked territory on the map is shared with a smaller reserve, Mississaugas of the Credit, in the southeast corner. Six Nations Reserve has about 30,000 members, the largest number of any reserve in Canada, of whom about 13,000 live on site. The Mississaugas of the Credit Reserve, an Ojibwe group, has about 3,000 members, of which about 1,000 live on the reserve.

Map 40A. A close-up of the northwest sector of Six Nations, including the enclave north of the river and the village of Ohsweken (pop. about 1,500), the site of the Reserve’s government and administration. Numbers on the map refer to the location of the entries numbered below.

Six Nations Reserve welcomes visitors. Access is chiefly by car (or by boat along the Grand), and there’s a new daily 15B GO Bus route extension with stops in both Reserves leaving from Aldershot and Brantford. From the north, Highway 54 between Brantford and Caledonia joins Chiefswood Road which runs south directly into Ohsweken via a bridge (CB) over the Grand. CW refers to Chiefswood Park. There are several roads into the reserve from Highway 6 to the east, notably 4th Line which runs into Ohsweken. Indian Line west of Hagersville forms the southern boundary of the two reserves. From it there are several roads into the reserves including the southern stretch of Chiefswood Road.

My focus, as always, will be on the Grand River and its vicinity. On the map above the Grand as it flows past the Reserve is also given its Mohawk name, Ó:se Kenhionháta:tie, the Willow River. Both in the Reserve and on its periphery there is limited access to either riverbank, as much of the land is private. We’ll follow the Grand from where we left off in the previous episode. Roadside P is available near most locations described.

535. Onondaga is a village on the north bank of the Grand just west of the border with Six Nations. Its name indicates that it was formerly the site of the post-Haldimand Proclamation settlement by the First Nation which is the Fire-Keeper of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The land on which it sits was surrendered (see #537 below) in 1839. Formerly a township, now Onondaga is one of the few population centres of Brant County. This building of buff brick, which the plaque on the front indicates was built in 1874, was first a school and then the township council chamber until 1976. It was saved from demolition a decade ago, and now houses a Brant County Custom Services Office.

536. Front Street in Onondaga runs alongside the north bank of the Grand for about 500 metres There’s an elevated viewpoint over the river – the view is better once the leaves have fallen – from near the junction of Painter Road and Brantford Street. What was once the extension of Front Street is now an unmaintained paved road that runs east along the river’s edge towards Six Nations, until it gets lost in a jungle of sumac.

537. There are few riverside trails in this area, and it’s not easy to follow the Grand downstream on public roads. On the south bank, River Road will take you no farther east than the hamlet of Newport, where the road is blocked. You can access the next section of River Road from Greenfield Road and then Fawcett Road, but you’ll find another roadblock at Bateman Line. It’s possible that flooding was the cause of these closures. If you want to enter Six Nations from the west, use Old Greenfield Road, which becomes 3rd Line in the Reserve.

On the north bank, Salt Springs Church Road will take you as far as the church of that name. This was the site of a Mohawk cemetery from 1822, and a wooden Methodist mission church was built soon thereafter. The church was hit by lightning and burnt down in 1901; the current building was rebuilt after that.

This territory was all part of the Haldimand Grant. This area, known as Davisville, was surrendered by the Six Nations in 1841. “Surrendered” is a term that needs unpacking. In 1883, it was clear to Charles Pelham Mulvaney, the early historian of Brant County, what had happened: “For a period of about ten years prior to 1841, the Indians experienced the full force of the iniquities the defective title to the lands they occupied entailed. When the whites began to encroach upon their domain, the Indians attempted to lease or sell the land to them, supposing their title to be absolute. But to this proceeding the Government objected upon the ground that the Crown had a pre-emptive right, and that the land belonged to the Indians only so long as they might choose to occupy it. This shameful state of affairs was not long in creeping through the brain of the deluded Indians; they at once saw their helplessness, and the only way out of their difficulties with the white settlers was to surrender the territory to the Government, which they did on the 18th of January, 1841” (Mulvaney 411).

Note: Natives in Canada could not vote in 1841, and only a few exceptions to this policy were allowed. After Confederation in 1867, Natives who did qualify to vote had to give up their treaty status to do so. In 1954 Natives in Ontario were given the vote in provincial elections, and in 1960 they were allowed to vote in federal elections without losing their status. Even now, many Haudenosaunee associate the franchise with the policy of forced assimilation (see #551 below), and are reluctant to exercise it.

538. Salt Spring Church Road has been closed at this point just east of the Church since 2021, as a result of riverside erosion. Brant County has recently voted to realign the road away from the river at a cost of $2.6 million.

539. We’re now on the northwestern part of the Reserve. There’s a section of 4th Line/River Road that follows the Grand closely. To get to it from the west, take 3rd Line to Mohawk Road, head north to where it meets the River at Grand River United Church, then turn west. To get here from the east, simply continue along 4th Line. This road is blocked after about 2.3 km and there is no vehicular access to Bateman Line or the continuation of River Road.

Above are some scenes from this very peaceful dead end.

540. Now we enter Six Nations Reserve the more usual way, from the north. This building, the HQ of Six Nations of the Grand River Development Corporation (SNGRDC), is at the junction of Pauline Johnson Road and Hwy 54. The aim of SNGRDC is to become a player in the regional economy and invest profits back into the Reserve. Major projects include involvement in the construction of Canada’s largest battery storage farm, smaller ones include scholarships and bursaries for students in fields associated with renewable energy. See Celeste Percy-Beauregard, “‘We’ll Have Full Autonomy’: Six Nations Development Corporation Building Economic Self-Sufficiency without Compromising Traditional Values,” Brantford Expositor (May 12, 2025).

Note: “development” according to traditional Haudenosaunee values differs considerably from the way much of the Western world defines it. For the Haudenosaunee, it’s the responsibility of all of us as humans to develop a respectful relationship with the earth and all living creatures on it. “This is a philosophy considerably different than what development has come to mean for the Western world, where ‘progress’ is viewed in materialistic measurements of time and money and most always results in environmental degradation” (Monture, We Share Our Matters 222-3) … degradation which, if allowed to continue, can surely only lead to catastrophe.

541. Our next stop is Chiefswood Park on the north bank of the Grand. The centrepiece is Chiefswood (top), the house constructed by Chief George Henry Martin Johnson (a.k.a. Onwanonsyshon, 1816-84) (bottom) between 1853-6. (We have already met Chief George, who was a friend of Alexander Graham Bell; see #508 above). George Johnson, a hereditary Wolf Clan chief, spoke both English and Mohawk and served as an interpreter to Anglican missions to the Six Nations and to the British Government. In 1824 he married Emily Susanna Howells, an Englishwoman whose abolitionist father had moved the family to the USA to help in the Underground Railway that aided escaped slaves to flee to Canada. The Johnsons had four children: Henry Beverly, Evelyn Helen Charlotte, Allan Wawanosh, and Emily Pauline.

The main house is built of local walnut with stucco cladding and has eight rooms, four up and four down. There are two front doors, one facing the river and one facing away. The house was willed to Six Nations Reserve by Evelyn, the last survivor of the four Johnson siblings, who died in 1937. Recognized as a National Historic Site in 1953, it opened as a museum in 1963. Between 1984 and 1997 it was closed for restoration to the state that it was in the mid-19th century, with William Morris wallpaper and a rebuilt summer kitchen.

Chiefswood is open between Victoria Day and Thanksgiving Weekends, Tuesday – Sunday 10:00 am – 3:00 pm; $15 for a guided, $10 for a self-guided tour. Pauline-Johnson-related merchandise is available for purchase in the gift shop.

542. Emily Pauline Johnson (a.k.a. Tekahionwake, 1861-1913), the youngest of the four Johnson children, was born and spent her childhood here at Chiefswood, spending much time paddling a canoe on the Grand. She started composing poetry at age 10, probably inspired by her paternal grandfather John “Smoke” Johnson (a.k.a. Sakayanwaraton, 1792-1886), a gifted orator and storyteller and a Pine Tree Chief* in the Confederacy Grand Council. Above is an autographed celebrity photo of Pauline, courtesy of Chiefswood.

*A Pine Tree Chief is not a hereditary position, but one given to someone whose outstanding personal qualities qualify him to participate in Grand Council decision-making.

543. Pauline Johnson’s poetry caused a sensation in her lifetime, and she capitalized on its success by performing it in public internationally. In the first half of her shows, she dressed in “Indian” regalia (left) and in the second half in a European ballgown (right), using her mixed heritage to suggest a bridge between two cultures. Not a modernist, she wrote in the nineteenth-century tradition of Tennyson, Browning, and Longfellow. She was an accomplished poetic technician, and her poems that mingle “exotic” Mohawk elements, sexuality, and violence, are still stirring. The dramatic monologue “Ojistoh,” for example, from her volume The White Wampum (1895), is told by the wife of a Mohawk chief who has been abducted on horseback by one of her tribe’s mortal enemies, a Huron warrior. This is how she rescues herself:

I, bound behind him in the captive’s place,

Scarely could see the outline of his face.

I smiled, and laid my cheek against his back:

“Loose thou my hands,” I said. “This pace let slack.

Forget we now that thou and I are foes.

I like thee well, and wish to clasp thee close;

I like the courage of thine eye and brow;

I like thee better than my Mohawk now.”

He cut the cords; we ceased our maddened haste

I wound my arms about his tawny waist;

My hand crept up the buckskin of his belt;

His knife hilt in my burning palm I felt;

One hand caressed his cheek, the other drew

The weapon softly – “I love you, love you,”

I whispered, “love you as my life.”

And – buried in his back his scalping knife.

Pauline Johnson’s legacy is extremely complex. One the one hand, as a woman writer with an international reputation who identified strongly as both a Mohawk and a Canadian, she was an important figure and role-model in the development of Indigenous, Canadian, and women’s literature in English. On the other, as an Anglican from a relatively privileged biracial background who could pass as white, her example seemed to many to indicate that the gathering assimilationist forces in Victorian Canada would eventually triumph and the “pagan, savage” Indian would disappear. There is no easy way of evaluating her influence.

While her three siblings are interred at the Mohawk Chapel, Pauline’s ashes are buried in Stanley Park, Vancouver.

For a brief summary of Pauline Johnson’s legacy see Charlotte Gray, “The Complicated Case of Pauline Johnson”; for more detail, see chapter 2 of Rick Monture’s book We Share Our Matters.

544. Some of the artifacts and furniture from Pauline Johnson’s time on display in the Chiefswood museum.

545. Bee hives at Chiefswood Park.

546. A boat dock and recreational kayaks by the Grand in Chiefswood Park.

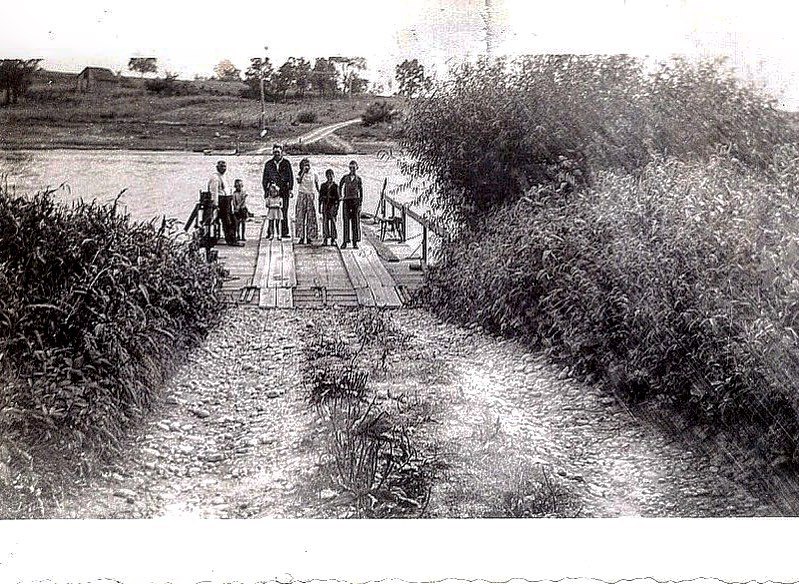

547. As there were no bridges across the Grand in the early days of Six Nations Reserve, hand-operated ferries would convey passengers and wagons across the river. “Each ferry is capable of carrying two teams and vehicles, and is propelled by an endless chain, which is attached by a windlass and crank to the boat and worked by hand. They are clumsy affairs at best, and the wonder is that they answer their purpose as well as they appear to do, or that they are a safe means by which to cross so wide and deep a stream as the Grand River” (Mulvaney 420). In 1883 there were four ferries between Newport and Middleport, the fare being 15 cents for a wagon. A crossing was free for pedestrians when accompanied by a wagon.

This undated poem, “At the Ferry” by Pauline Johnson, which describes waiting for one of those ferries, was the only one I could find by her in which the Grand River is specifically named:

We are waiting in the nightfall by the River’s placid rim,

Summer silence all about us, save where swallows’ pinions skim

The still grey waters sharply, and the widening circles reach,

With faintest, stillest music, the white gravel on the beach.

The sun has set long, long ago. Against the pearly sky

Elm branches lift their etching up in arches slight and high.

Behind us stands the forest, with its black and lonely pines;

Before us, like a silver thread, the old Grand River winds.

Far down its banks the Village lights are creeping one by one;

Far up above, with holy torch, the evening star looks down.

Amid the listening stillness, you and I have silent grown,

Waiting for the River ferry, — waiting in the dusk alone.

At last we hear a velvet step, sweet silent reigns no more;

Tis a barefoot, sunburnt little boy upon the other shore.

Far thro’ the waning twilight we can see him quickly kneel

To lift the heavy chain, then turn the rusty old cog-wheel;

And the water-logged old ferry-boat moves slowly from the brink,

Breaking all the stars reflections with the waves that rise and sink;

While the water dripping gently from the rising, falling chains,

Is the only interruption to the quiet that remains

To lull us into golden dreams, to charm our cares away

With its Lethean waters flowing ‘neath the bridge of yesterday.

Oh; the day was calm and tender, but the night is calmer still,

As we go aboard the ferry, where we stand and dream, until

We cross the sleeping river, with its restful whisperings,

And peace falls, like a feather from some passing angel’s wings.

The typescript of the poem is in Six Nations Public Library, Ohsweken.

548. A young man in Chiefswood Park cools off in the Grand on a hot day.

549. The Grand looking downstream from the bridge on Chiefswood Road. This bridge will be most visitors’ point of entry to Ohsweken.

550. An old plaque in Six Nations Veterans’ Park in Ohsweken expresses the half-truths, distortions, and wishful thinking associated with the British Empire in 1934. Let’s briefly annotate its claims.

*The Mohawks of Kahnawake supported the French against the British at the start of the Seven Years War.

*Most of the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the American Rebels in the Revolutionary War, as did the Mohawks of the Stockbridge Militia.

*The British failed even to mention, let alone accommodate, their Six Nations allies in the Treaty of Paris (1783) with the Americans after the Revolution. This unforgivable omission led to Six Nations’ forced exodus from New York State into Upper Canada.

*While Mohawk and other Native warriors did play a crucial role in repelling the American invasion of Upper Canada in 1812-14, Six Nations saw little benefit in its aftermath. Peace led to an invasion of white squatters on their Grand River territory and, ultimately, their forced surrender of much of the remaining Haldimand Tract.

*Some Six Nations warriors did serve under William Johnson Kerr in helping to put down the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-8, but only because there were false rumours that the Reformist Rebels planned to confiscate Grand River lands.

This plaque belongs in a museum, framed with clarifying footnotes!

551. The former Six Nations Council House (1863) on 4th Line by Six Nations Veterans Park.

This was built for the Confederacy Grand Council, the traditional form of governance of the Six Nations based on the Kaianere’kó:wa, the Great Law of Peace. Haudenosaunee descent is matrilineal: the women who are Clan Mothers choose fifty Hereditary Chiefs, and may remove them too. The Six Nations Council at Grand River is one of two independent governing councils, the other located in Onondaga, New York. The chiefs must reach unanimous agreement to take action on any issue, and decisions must take into account seven future generations. “It’s what’s been called the oldest form of democracy, where leaders served the people, as opposed to the other way around, which is what happened in Europe at the time” (Monture, “Q&A”) … or what is happening in much of the world at present, one might add.

However, in 1924, the Indian Act imposed Western-style governance upon Six Nations: an elected Band Council of one Grand Chief and nine counsellors, with majority rule replacing unanimity. In one of the more shameful episodes of that period, on 7 October 1924 armed RCMP removed the hereditary chiefs from this building under the orders of Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who believed in imposing assimilationist policies, forcibly if necessary. His aim was the ultimate disappearance by absorption of the problematic Indian from Canadian society.

Notwithstanding, the traditional Six Nations Grand Council of hereditary chiefs still meet regularly to discuss community issues. The Confederacy Council and their supporters continue to assert their own legitimacy as the government of a sovereign independent nation who are allies, not subjects, of the Crown – and as the equal of the Government of Canada.

552. The Haldimand Proclamation Memorial is a four-sided column in black marble on the grounds of Six Nations Sports and Cultural Memorial Centre.

(Top) One side reproduces the whole text of the Haldimand Proclamation.

(Middle) Another side is taken up with the iconography of the Great Peace of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy: the Guardian Eagle atop the White Pine Tree on the back of a Turtle (North America) with the buried weapons of war below.

(Bottom) Another side reproduces one of the original maps of the Haldimand Tract, with a portrait of Joseph Brant looking down on it. The Two-Row Wampum on the base below symbolizes the separate-but-equal agreement made between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch colonists in 1613. The Two-Row Wampum continues to serve as a model for the Six Nations to aspire to in their relation to the Canadian government.

Other images depicted on the base include those representing the Haudenosaunee clans of the Turtle, Eel, Beaver, Wolf, Deer, Bear, Snipe, Hawk, and Heron; and the Ayenwahtha Wampum Belt, symbol of the original Five Nations Confederacy.

553. A detail of the Tom Longboat Memorial beside Six Nations Sports and Cultural Memorial Centre. Thomas Charles Longboat (a.k.a. Gagwe:gih, 1886-1949), an Onondaga from Six Nations Reserve, was the greatest long-distance runner of his age and a world-famous sporting celebrity. In 1907 he won the Boston Marathon by a record margin and he became Professional Long Distance Champion of the World in 1909. He had been educated at the Mohawk Institute Residential School (see #525 above) and later remarked, “I wouldn’t even send my dog to that place.” He served as a dispatch carrier on the Western Front in World War I and was twice wrongly supposed to have been killed in action. After the war he worked in Toronto and returned to Six Nations on retirement, dying here in Ohsweken. The memorial, designed by Mohawk/Oneida artist David General (b. 1950) and including the statue above, was on display at the Pan American Games in Toronto in 2015, then moved here to Ohsweken.

554. Symbolic images line the front wall of Six Nations Sports and Cultural Memorial Centre in Ohsweken, each representing the meaning of the name of the Nation in its own language. Mohawk: People of the Flint or Chert; Oneida: People of the Standing Stone; Onondaga: People of the Hills; Cayuga: People of the Pipe or Great Swamp; Seneca: People of the Great Hill; Tuscarora: People of the Hemp Shirt.

555. Brandon Montour (b. 1994), a defenceman with the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League, is the latest former resident of Ohsweken to find fame. Montour, who is Mohawk on his father’s side, is the first member of Six Nations of the Grand River ever to win a Stanley Cup, professional ice hockey’s greatest prize. Montour brought the actual cup to Ohsweken in July 2024 and was given a hero’s welcome.

556. The water tower at Ohsweken. The meaning of the town’s name and its pronunciation vary, given that there are six national languages at play here. The spelling on this side of the tower is the Cayuga form. The Mohawk form is Oshwé:ken, which tends to determine the way the name is pronounced by outsiders.

On the subject of water: while Six Nations Reserve looks like many other semirural areas of Ontario, the scandalous fact remains that 70% of people on it have no access to safe drinking water in spite of living in close proximity to the Grand River. See this well-illustrated CBC Report: Jaela Bernstien, “There is a community outside Toronto where most people can’t drink their tap water. Patience is running out” (12 September 2024)

557. “Tobacco Road” is a 4 km section of Highway 54 through the enclave of Six Nations Reserve on the north side of the Grand.

All forms of public tobacco ads are banned in Canada, and cannot appear on billboards, television, radio, or in newspapers. Even tobacco event sponsorships are strictly prohibited. But not on First Nations Reserves. The very low advertised prices are usually available to Status Indians with ID buying “Native Smokes” like BB and Canadian Goose cigarettes. Non-Natives will almost certainly pay less for national brands than they would outside the Reserve.

Before condemning “Tobacco Road” and its ilk, consider the following, from a historian of Native America: “Woodland Indians of North America smoked dried tobacco in pipes, and the Indians of Mexico and the southwestern United States rolled it into corn husk cigarettes to smoke … Tobacco was the first of the New World drugs to be widely accepted in the Old World, and the European zest for it played a major role in opening North America to colonization … When adopted by westerners, tobacco had no culturally prescribed place as it did among the Indians. Its use grew indiscriminately and soon became pervasive, with people smoking, chewing, spitting, and snorting tobacco in the streets, at the dinner table, in bed, and in classrooms” (Weatherford 259-62).

558. The hamlet of Middleport is the first settlement east of the Reserve along Hwy 54. This is what it was like in 1883: “Middleport is beautifully situated on elevated ground, commanding a fine view of the river and surrounding country. It took its name from the circumstance of its location being midway between ‘the locks’ near Brantford and the Village of Caledonia. In its palmy days it was an important port of the Grand River Navigation Company’s lock and river system. Large quantities of timber were shipped from here, which gave the place a brisk, business-like appearance, but with the decline of the Navigation Company’s fortunes, and the exhaustion of the timber in the vicinity, the prosperity of the village was checked … The first post office in the township was established here, and named Tuscarora … A ferry is located at this point, which is extensively utilized by people who cross the river to and from the Indian Reservation opposite. Middleport is a flag station on the Grand Trunk Railway, which passes to the rear of the village, about three quarters of a mile distant.” (Mulvaney 427).

(Top) St. Paul’s Anglican church (1864) began as a mission to the Six Nations about 1822.

(Middle) The cemetery by the church is right on the riverbank.

(Bottom) This magnificent rooster surveys his harem of hens near the cemetery.