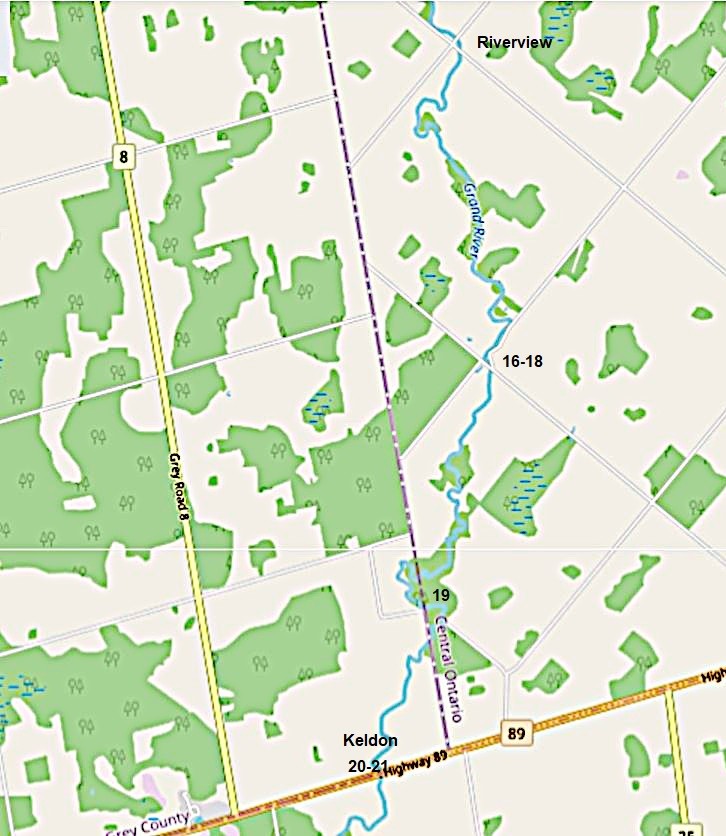

Map 3.

This map shows the Upper Grand basin in some detail. (Yes, the mapmaker has misspelled “Melancthon.”) Today we’ll go from the hamlet of Riverview to Grand Valley, the first town of any size on the Grand. This stretch of the river passes almost entirely through private land, so I’ll be driving between those locations, stopping on or near bridges on public roads to view the Grand as it slowly increases in size in its southward course.

It’s about a 20 minute drive between Riverview and Grand Valley, but I won’t be going directly. I’ll be making a short detour via Luther Dam (near the northeast corner of Luther Marsh above). That’s because Luther Marsh, behind the dam, is the chief feeder of the Upper Grand, via Black Creek. And the Upper Grand as we know it has been shaped by its relationship with Luther Marsh.

Rivers were highly significant in the early history of human settlement. They provided essential fresh water to those who first settled their banks. And they served as the primary means to transport people and goods over distance inland. Rivers today may have lost some of their practical importance, but they remain a powerful cultural presence. A river offers mental images that better enable us to grasp by analogy such intangibles as the course of human life, the ever-changing face of the world, and the nature of Time itself. I’ll be exploring the river as metaphor as I descend the Grand.

Map 4. Riverview to Keldon

The local maps in this photoblog are all reproduced courtesy of OpenStreetMap and its contributors. Numbers along the Grand River on these maps refer to blog entries with those numbers.

16. The (not-so-) Grand River from the bridge on 8th Line SW (Melancthon) looking south.

The authoritative Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines river as a “large natural stream of water flowing in a channel to the sea, a lake, or another stream.” By this definition, the Grand above is not a river as no one would call it “large.” Rather, it better fits the OED definition of creek: “In U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.: A branch of a main river, a tributary river; a rivulet, brook, small stream, or run.” (We are not done with the OED.)

17. A biker opens up on 8th Line SW. Most roads hereabouts are gravel and lightly trafficked.

18. A huge wind turbine looms on the crest of a rise above 8th Line SW close to its junction with the Southgate-Melancthon Townline.*

*A townline is a road that forms the border between two current or former townships (i.e., rural municipalities). The Grand, like many rivers, would seem to provide an obvious natural boundary between municipalities. But as it inconveniently doesn’t flow in a straight line, and the boundaries between townships are usually straight, the Grand sometimes weaves in and out of neighbouring townships.

19. The Grand from the Melancthon-Proton Townline. The former Proton Township, named in 1827, has nothing to do with the subatomic particle discovered by Ernest Rutherford in 1920, except that both words are derived from the Greek word meaning “first.” Proton has now been absorbed by Southgate Township.

The latest version of the OED is online only, but if you print out its entry on river, you’ll find you have more than 38 pages. The entry’s etymological section indicates that river is Anglo-Norman in origin and first appears in English around 1300. It’s thus a close relative of modern French rivière, which means something like “a smaller river that flows into a larger one.” (The French for a big river that flows into the sea is fleuve.) Both English and French words descend from the Latin adjective riparius, which means “of the bank of a river,” not a river itself.

The various meanings of river, current and obsolete, take up more than 10 pages of the entry. Then the OED tells us that river is one of the 2,000 English words most frequently found in print today, a measure of its very high cultural importance. The entry ends by listing in chronological order of their first appearance in English all the compound words and phrases containing river. There are almost 300 of them, from riverward (from c. 1380), to atmospheric river (from 1994), that harbinger of today’s climate crisis.

20. At last: the first roadside sign identifying the Grand, at Keldon on Ontario Highway 89. This is a paved east-west highway, important enough to be maintained by the province rather by the local municipality.

21. The Grand from the bridge on Ont. 89 at Keldon looking south.

Keldon today is a sub-hamlet of half a dozen dwellings, whereas formerly it was a village with its own store and church. If you live in Keldon now you are car-dependent to say the least. It’s more than 15 km to the closest shops and services in Shelburne. In the later 19th century, Keldon was where the Grand grew wide and deep enough for lumber to be floated downstream to rail shipping points farther south. Now it’s hard to imagine anything much bigger than a popsicle stick floating easily down the placid shallow creek that is the Upper Grand in August.

22. (Top) From the bridge on Concession* 12-13 looking north. We’re now in the Town of Grand Valley, which is a municipality (a township) and not to be confused with the actual town of Grand Valley (see #38-50 below). The Town of Grand Valley was so named in 2012, before which it was called (less confusingly) the Township of East Luther Grand Valley.

(Bottom) You can tell that this brief widening of the Grand is a fishing hole from the floats and tangled line caught in an overhead power line.

*A “’Concession line’ is principally an Ontario term for the straight country roads, parallel to one another, upon which farm lots face. They are complemented by perpendicular side roads, which together create a gridwork that covers each respective township. Each rectangle of roads commonly embraces 10 farm lots of 100 acres (40.5 ha) in size. During the 19th-century era of initial settlement in Ontario, these lots were conceded (hence “concession”) by the Crown to individual applicants seeking title in exchange for raising a house, performing roadwork and land clearance, and money” (The Canadian Encyclopedia).

23. Now we’re on the bridge over the Grand on Dufferin County Road 15, a.k.a. Concession 10-11, west of the hamlet of Colbeck looking south. You can see that the river is still only a few inches deep at this point. And if you can wade it that easily, it’s a creek!

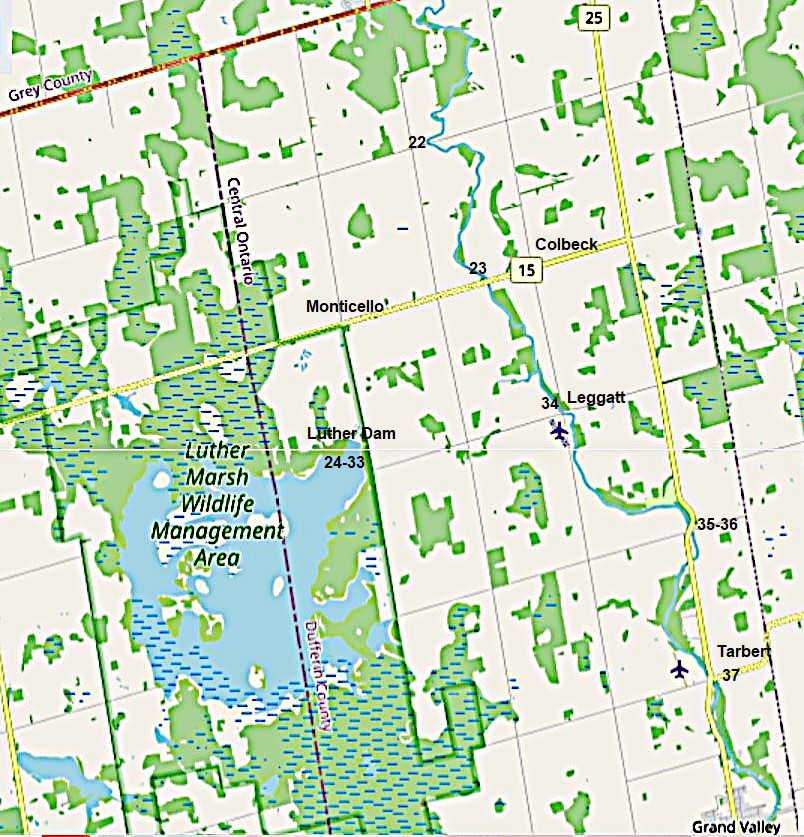

Map 5. Luther Marsh to Grand Valley

24. Time to make our detour. We enter Luther Marsh WMA by going south from Monticello along Sideroad 21-22.

Why “Luther”? Mabel Dunham tells this story: “This enormous bog … is often called the Luther Swamp. These names, so reminiscent of the Protestant Reformation, are said to have been assigned by a Roman Catholic whose ire was aroused when he was surveying the swamp. Luther and Melancthon, he said, were the names of the worst men in history. It was appropriate that they should be given to the worst swamp he had ever seen” (264).

The story is a good one but almost certainly untrue: the names had been attributed before the Catholic surveyor, George McPhillips, surveyed the area in 1854. However, Luther Marsh, now valued as a large biodiverse wetland, did cause serious problems for settlers who attempted to farm it in the early 19th century. Arriving too late to claim any better farmland, they tried their hardest to tame an intractable bog. As seed they sowed rotted, they turned to the extraction of lumber (cedar and tamarack), but the loss of restraining roots caused flooding downstream, not only on the Grand but also on its major tributary the Conestogo, whose headwaters are on the west side of the swamp.

Only in more recent years has the Grand’s cycle of spring flooding and summer drying-up been broken by careful water management, of which the dam here plays an important part. The Grand River Conservation Authority, which oversees the marsh, has its origin in the 1930s. Its mission today is to “work with local communities to reduce flood damage, provide access to outdoor spaces, share information about the natural environment, and make the watershed more resilient to climate change.” As the sign above suggests, Luther Marsh now welcomes bird watchers (263 species spotted), hunters (waterfowl, deer, rabbits), and hikers and cyclists (it’s about 32 km around the lake). Fishing, however, is poor as the lake is shallow and full of aquatic vegetation.

25. The marsh at this point presents itself as vast, tranquil Luther Lake – technically it’s a reservoir – that provides magnificent cloud reflections.

26. The French Impressionist Claude Monet, who made more than 250 paintings of waterlilies, would have felt right at home here. Compare these Lutheran lilies to Monet’s here.

27. At the edge of the lake you can get up close to Joe-Pye weed (see #3 above). Curious about this plant’s name? A recent scholarly article engages the question definitively, even identifying Mr. Joe Pye himself. See Pierce 177-200.

The marsh is at a high elevation and winters are harsh. Here you can find sub-boreal plants such as black spruce, sphagnum moss, and cotton grass.

28. There’s a observation tower on the shore of the lake, from which you can spot Luther Dam.

29. On Luther Dam looking west.

This low-cost, low-profile dam, which turned the marsh behind it into a reservoir (it took three years to fill), was constructed in the early 1950s at the point where Black Creek emerged from the former swamp. Black Creek is the major headwater of the Upper Grand basin. The aim of the dam was to control the flow of water in the Upper Grand, and especially to ensure that the river didn’t dry up in summer, as it was wont to do. As we shall see, it would take more elaborate water control measures downstream to stop spring flooding in more thickly populated areas.

30. This little hut houses the machinery to operate the sluice in the dam …

31. … and that sluice at the moment is releasing water from the lake …

32. … into Black Creek, which flows away to the east. It’ll join the Grand on private land about 4 km away.

33. Luther Lake is a notable sanctuary for waterfowl, though I’d have needed powerful binoculars to spot any on my visit. However, this Eastern kingbird was prepared to pose for me by Black Creek, and even demonstrate its aerobatics when catching insects. Its Latin name Tyrannus tyrannus indicates that this modestly-sized flycatcher is an aggressive defender of its territory. Most other birds, including much bigger raptors, don’t mess with kingbirds.

34. We return to the Grand. This is the view from Concession 8-9 near Sideroad 27-28 at Leggatt, looking north.

According to Roy MacGregor, “in the summer of 1936, the river vanished, its bed completely dry for some eighty kilometres between its source near Dundalk and the town of Fergus” (160). Thanks to Luther Dam, this is unlikely to happen again.

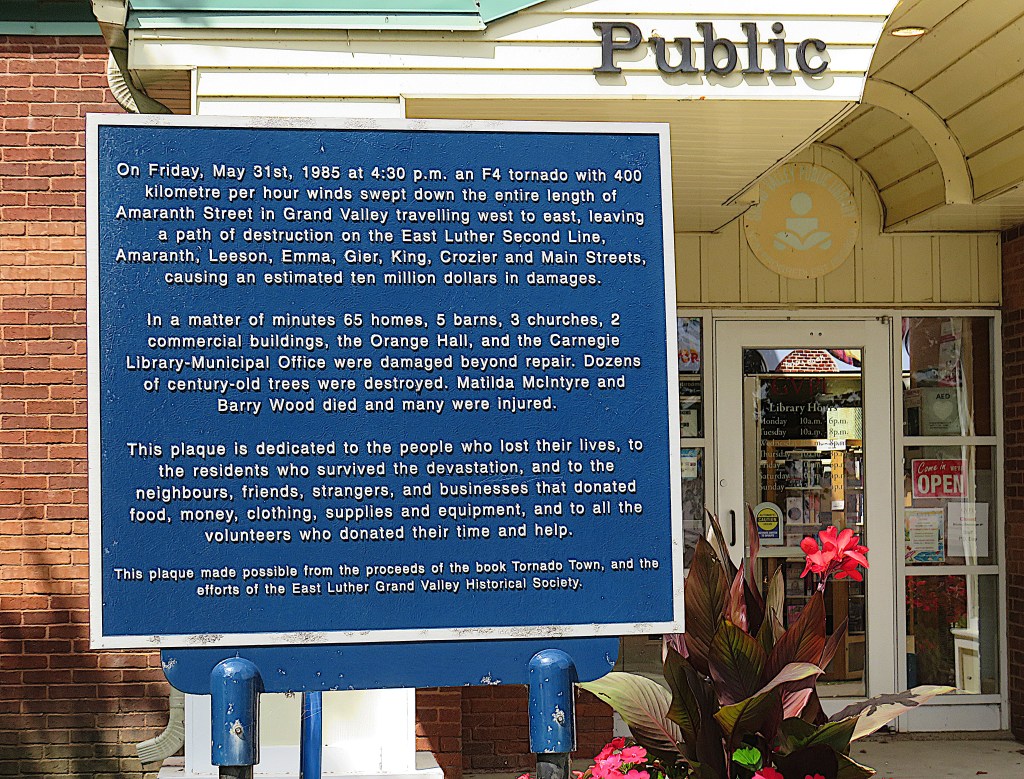

The Grand, augmented by water from Luther Lake, is now starting to look more like a river.

Leggatt once boasted a post office, but today it’s little more than a name on the map that embraces a handful of local farms.

35. County Road 25 at Concession 6-7 looking south. Those are the remains of an earlier bridge across the Grand.

36. County Rd 25 south of Concession 6-7 looking northeast.

Why does it seem more natural to follow a river from its source to its mouth, as I’m doing, rather than the other way around? Isn’t it because a river has a beginning, middle, and end, and I’m telling its story in that order? In spite of modernist and post-modernist narrative practices, that’s the way most stories have always been told because it’s the easiest way for audiences to follow them …

37. Near the junction of County Roads 10 and 25 at Tarbert looking north.

… but as with all stories, only certain incidents signify, and so the intervening time between them can profitably be omitted. It’s simply too boring (are you listening, James Joyce?) to recount every single event that takes place in, say, one day in the life of a main character. As my protagonist is a river, I’m leaving out of my documentation long stretches of it, just as film editors used to leave long strips of celluloid on the cutting room floor, knowing that the film will be all the better for what’s left out. (As it happens, I don’t really have a choice, as most of the Upper Grand is on private land and inaccessible.)

Tarbert once had two churches, Presbyterian and Methodist, almost identical and standing only a few yards apart. In 1904 Tarbert’s schoolhouse became too small for the number of kids attending and a new one was built for 28 pupils. But by 1968 the school was closed and the few remaining pupils were bussed to Grand Valley. Thanks to rural depopulation, Tarbert, like Keldon and Leggatt, is now little more than a name on a map. But these lost villages along the Upper Grand do have histories. You can learn more about them here.

Map 6. Grand Valley

38. The centre of Grand Valley – the town, not the Town – from near the junction of Main Street and Amaranth Street looking south. Main Street dips picturesquely down to where it crosses the river whose name it shares, then slopes up again beyond. Grand Valley (current pop. about 3,000) was founded as Joyce’s Corners, was known as Little Toronto for a while after the railroad came in 1871, then briefly became Manasseh, and then Luther Village. Its name was finally established as Grand Valley by a conclave of townspeople in 1886.

39. This plaque stands outside the current library (1988) on Amaranth St. East. The fate of the old library is mentioned on the plaque.

40. Grand Valley was used to periodic disasters in the form of flooding by the Grand River. But the tornado of 1985 was completely unexpected, and left a trail of destruction along Amaranth Street.

41. Amaranth Street East looking east today. The street is named for the neighbouring Amaranth Township to the east. “Amaranth” is a rather more euphonious synonym for the pigweed that grows locally.

42. Fishing from the Amaranth St. bridge. Supposedly smallmouth bass and pike are caught hereabouts, but no trout make it this far upstream. This bridge was first built about 1873, then washed away by a flood in 1883 and then again in 1918. The present concrete bridge was built in 2002.

43. The Grand from the Amaranth St. bridge looking southwest. The river here has been tamed by Luther Dam upstream. It wasn’t always so.

“As March 1929 blended into April, the residents of Grand Valley were breathing easy for a change. In springtime, keeping a wary eye on the Grand River as it loops through town is a long-ingrained community habit. But that year the snow had melted evenly, and most important, the ice cover had floated away without creating a dam. It seemed that ’29 was going to be a no-flood year. Until the afternoon of Friday, April 5.

“On that day, the clouds opened with a force no one could recall seeing before. By early evening, town constable Stuckey was visiting village homes along the flood plain urging families to evacuate. By midnight, three feet of water covered the south end of town with a fierce, swirling current. And the level kept rising, for north of the village the normally placid Black Creek was pouring the waters of Luther Marsh into the Grand. By three a.m., water on the road south of the village approached the height of an adult. Power went out. Telephones didn’t work, roads were closed and trains were halted by washouts. Grand Valley was in a crisis and on its own.” (Ken Weber).

Actually, because Grand Valley was used to inundation, it was better prepared for this, the 1929 “Flood of the Century,” than larger communities like Fergus and Elora downriver, which were devastated. It was this event that made it clear to everyone who lived in the Grand watershed that an effective policy of water management needed to be urgently implemented.

44. This eatery with its suspended patio is on the southwest corner of Main and Amaranth. This was the original location of Joyce’s Tavern, the log structure erected by a Mrs. Joyce and her sons and one of the first buildings in Joyce’s Corners, later Grand Valley.

45. Main Street looking north, the reverse angle of #38 above. The central townscape, most of it more than a century old, is nicely preserved.

46. This is where Main Street meets the Grand River. Grand Valley is one of the few settlements on the Grand that seems entirely at ease with the river. This was not always the case.

47. The Main Street bridge (1994) at Grand Valley. Its decorations suggest that this is a community that now loves, rather than fears, its river. Yet the first Main Street bridge was wrecked by a flood in 1901, then rebuilt, then wrecked again in 1918.

48. From the Main Street Bridge looking north.

49. Grand Valley Park occupies the eastern bank of the Grand south of the business district. It’s really the first area on the Upper Grand where you can explore a good stretch of the riverbank without trespassing on private land.

50. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the Ghost of Hamlet’s father prepares to tell a horrific story to his son, the Prince of Denmark:

“I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres,

Thy knotted and combined locks to part

And each particular hair to stand on end,

Like quills upon the fretful porpentine …”

In Grand Valley Park, a father and son are walking their dog, which suddenly starts yapping at something moving in the middle of a lawn area. The porcupine, for so it is, takes absolutely no notice, browsing unperturbed on the grass. Porcupines are short-sighted, but this one certainly sees me as I move in for a close-up. It acknowledges my presence by raising its head one inch for one second. I think it feels so well armoured by its quills that it can afford to ignore just about anything in its vicinity that other wild creatures would immediately view as a threat. Nothing fretful whatever about this porpentine!