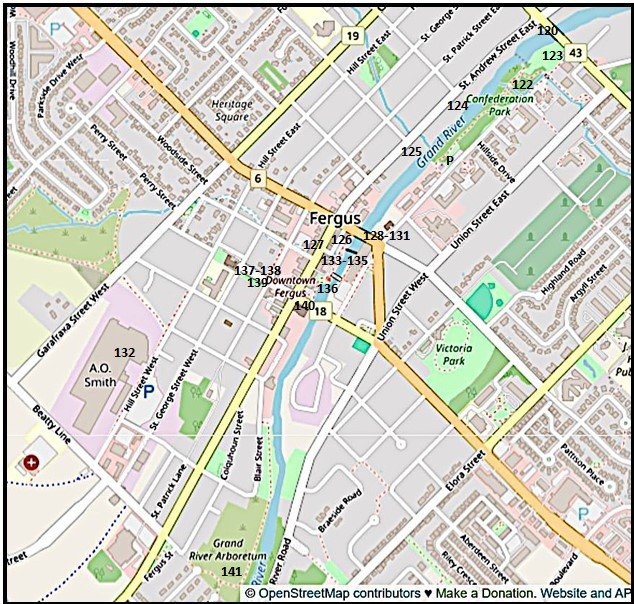

Map 12. Downtown Fergus

Numbers 120-149 on the map above correspond to the numbered entries below.

You can easily cover the sights in central Fergus in a couple of hours. P at Confederation Park on Queen Street East, and then do a loop, using Caldwell Bridge in the east and Tower Street Bridge in the west as your end points. Admire the Grand River from the St. David Street Bridge, the Templin Gardens steps, and the Milligan Footbridge. If you like domestic architecture, explore the streets off Tower Street North on the west bank of the River.

120. The view downriver from Caldwell Bridge on Gartshore Street (the Jones Baseline) in Fergus.

Fergus (pop. approx. 25,000) is a very pleasant town, the largest in Wellington County.* It was founded by two Scotsmen in 1833, and is one of the most Scottish-influenced settlements in Ontario. Fergus sits on a narrow, fast-flowing, almost straight stretch of the Grand. This made its location appealing to millers in the days when mill wheels were turned by water power alone.

At right above: the mill buildings (first established ca. 1856) at Wilson’s Dam. These buildings have been known by a variety of names – Monkland, Walkley’s, Groves – but since 2003 they have been St. Andrew’s Mill, a luxurious condo development.

As we know, Fergus is on land that was part of the Haldimand Grant of Grand River territory to the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in 1784. So what happened between then and 1833?

*The much larger city of Guelph may be geographically “in” Wellington County, but technically it’s an independent municipal entity.

121. Please bear with me. This story is complex and can’t be summarized in a couple of sentences.

Above is a detail of a redrawn, clearer version of the 1821 Ridout map (see #118 above) of the upper part of the Haldimand Grant. The Grand River takes a sinuous course southwest from its intersection with the Jones Baseline. No. 3 (“now Woolwich” Township) and No. 4 (“now Nichol” Township) are the two northernmost of the six blocks of land granted to the Six Nations that were put up for sale by Joseph Brant. His primary aim was to use the money from the sale to create a long-lasting revenue stream for his people. These two were the blocks most distant from the land actually occupied by the Six Nations after 1784, so were probably viewed by Brant as the most disposable. We’ll deal here only with Block 4 (“Nichol”), as what happened here exemplifies the problematic outcome of many of Brant’s land dealings.

Brant put Block 4 (28,512 acres/115.4 sq. km.) up for sale in 1798, but no buyer came forward. Later, one Joshua Cozens claimed he’d bought Block 4 from Brant in 1796, and “spent the rest of his life trying to substantiate his claim” (Charles M. Johnston, The Valley of the Six Nations, lxii). But as Cozens’s deed had never been sanctioned by the government of Upper Canada, who were acting as trustees for the Six Nations, his claim was continually rejected. Moreover, Cozens had never put down any sort of deposit. Cozens’s agent Samuel Clark pawned that deed for £250 to a London firm which then went bankrupt. Brant then sold the tract to a James Wilson, who was subsequently also unable to put down any deposit. When Wilson’s property went up in flames in 1799, Brant generously gave him £600!

In 1806, the government on behalf of Six Nations sold Block 4 to Colonel Thomas Clark, a Queenston merchant. Clark was supposed to have provided a bond for £4,564 payable to Six Nations, due in 999 years! As Mabel Dunham puts it, “This transaction is understandable only in light of the fact that the colonel’s charming wife was a grand-daughter of Sir William Johnson and [Joseph’s sister] Molly Brant” (Grand River, 149-50). If the government received any money from this transaction, there’s no evidence Six Nations saw any of it.

Joseph Brant’s frequent acts of generosity to his relatives and friends, native and white, are in stark contrast to the government’s neglect of its obligations to Six Nations. Also, the contrast probably suggests what was then a major cultural difference between First Nations and white settlers in their attitude to land ownership. There was an “ancient principle” among the Confederacy “that land ‘was not a commodity which could be conveyed’” (Johnston, xliv). So Brant’s land dealings went against the grain of his own cultural tradition, while antagonizing the paternalistic government of Upper Canada.

It’s unclear why Thomas Clark named the tract, not for himself, but for his cousin Robert Nichol, who had “no interest in the property” (Dunham, 150). Still, Block 4 was known as Nichol Township until 1999, when it became part of the current Township of Centre Wellington.

In December 1808 Clark sold the southern section of Block 4 to Samuel Hatt of Ancaster, who shortly thereafter sold it on to Rev. Robert Addison of St. Mark’s Church, Niagara. After Addison’s death, his widow sold all 13,816 acres at 7s 6d per acre to Capt. William Gilkison, a Scot who moved his family to Upper Canada, which he called “the only free country on the face of the globe that I know anything about” (155). Gilkison died in 1833, but not before he had planned what would be Fergus’s neighbouring settlement of Elora.

Meanwhile, Adam Fergusson, a Scottish lawyer, came to Upper Canada in 1831 on behalf of the Highland Society of Edinburgh to investigate how emigration might benefit his impoverished fellow Scots. He was delighted with the valley of the Grand in Nichol Township, “a land where superior men of character … might live an ideal life” (157-8). In 1833 Clark sold the northeast quarter of the tract (7,367 acres) to Fergusson and his ambitious young friend James Webster. The first house in Little Falls, as the settlement on the Grand River was first named, was built in December that year. Little Falls was incorporated as a village in 1850 and renamed Fergus, for either Fergusson or Fergus the mythical First King of Scotland … or both. In its early days, only Scots could purchase land in the settlement. If you were Irish, you had to go to nearby Arthur.

So, the government, acting as trustees for Six Nations, sold Block 4, but Six Nations apparently never received any of the purchase price or interest intended for their “perpetual care and maintenance.” This missing money plus more than 200 years’ compound interest is only one of the many claims in the 2020 booklet put out by Six Nations outlining their Land Rights in regard to the Haldimand Tract.

122. Back to the present. Confederation Park occupies much of the eastern bank of the Grand in central Fergus. There’s a free P on Queen Street East. The park has two aspects. There’s a dense forest with a trail through it …

123. … and there are lawn areas, like this one on the riverbank by the Caldwell Bridge that is a popular picnic spot.

124. Do you love old stone buildings? Fergus has about 200 of them, thanks to limestone quarried from the local riverbanks, sandstone later brought in from the Credit River by train, and the skilled Scottish stonemasons who settled in the town. St. Andrew Street East that runs parallel to the west bank of the Grand has several delightful stone domestic buildings, some of which have plaques noting who first built and occupied them. No. 396 (1858-68) is the locally-quarried limestone cottage of William Rennie, a farmer and real estate investor. One of seven such cottages in the town, It “represents the one-storey Ontario Cottage style: modest in size and popular among skilled craftsmen and labourers” (Nina Chapple, A Heritage of Stone, 32).

125. No. 296 (1891) was the home of Thomas Cumming, a carriage maker. This house glows in the low evening sunlight.

126. The main business section in Fergus is on St. Andrew Street West between St. David Street North and Tower Street. The three-storey Argo Block (1858) in Classical Revival style was one of the first major stone edifices in the town. It has that particular Scottish quality of austere solidity.

127. St. Andrew Street West downtown.

The national flag of Scotland, bearing the Cross of St. Andrew or Saltire, flies as prominently as the Maple Leaf on Fergus’s main drag. St. Andrew, i.e., Andrew the Apostle, is the patron saint of Scotland. He has been so since the 8th century AD when his sacred relics were brought from Constantinople to what is now the university town of St. Andrews, Fife.

128. The newly reconstructed St. David Street Bridge (2018) from the east bank. The Brew House on the Grand, since 2011 a popular pub, was built in 1851 as the home of a tanner. It was later converted into a flour mill and then into a hydroelectric generating station by Dr. Abraham Groves, a pioneer of electrification in the town.

129. The view upstream from the St. David Street (Ontario Highway 6) Bridge. The Grand flows fast and straight down a narrowing, deepening channel through Fergus, making its banks ideal sites for water-powered mills.

130. Fergus Cascade is a rapids just downstream from the St. David Street bridge. The building with the chimney at centre …

131. … is the former foundry (built 1854) occupied by Beatty Brothers from 1879. Here was the origin of the large agricultural machinery and (later) international domestic appliance manufacturing operation that had Fergus as its HQ. Now renovated, the building is the cornerstone of the Fergus Marketplace, a shopping and restaurant strip.

132. This was the Hill Street factory of Beatty Bros. Ltd., built 1911. It produced reapers, mowers, ploughs, stoves, and kitchen utensils, among many other items.

The Beatty Brothers, George and Matthew, founded their firm in 1874. Of Irish background, they were staunch Methodists who had a profound influence on Fergus for several generations. They believed, notably, that alcohol was the devil’s brew, so they bought then closed down the inns in town, and Fergus remained one of the driest towns in Ontario for years.

Though their plant was a notorious source of pollution into the Grand, Beatty Bros. was ahead of their time in terms of worker relations. Hearing that there had been drownings in Grand River swimming holes, in 1930 they built an outdoor swimming pool for their employees, heated by steam from their factory. They supported sports teams, workers’ bands, community theatre, and held an annual Fergus Factory Field Day picnic and a Christmas party for employees and their families.

By 1928 Beatty Bros. had 1,300 employees on payroll and was the largest manufacturer of washing and ironing machines in the British Empire. During WWII, the factory was converted to making munitions and staffed mainly by women workers.

Beatty Bros. was merged into General Steel Wares of Toronto in 1969, which was bought out by a US firm in 2006. The Hill Street factory continued to make water heaters until 2013, when it was finally shut down, ending the connection between Beatty Bros. and Fergus.

133. Milligan Footbridge spans the Grand at its narrowest in central Fergus. It offers great views of the River in both directions.

134. (Top) This is upper Templin Gardens (1934) on the west bank just downstream from the footbridge. The gardens were constructed during the Great Depression, having been commissioned by J.C. Templin, the editor of the local paper. The gardens fell into disrepair, but were restored on a smaller scale in 1970. You can descend by steps down to the edge of the Grand, at the point where it briefly widens into a whirlpool.

(Bottom) A monarch on buddleia may be a visual cliché, but it’s a beautiful one. Templin Gardens in summer is a good place to see this tableau for yourself.

135. The view from the footbridge downstream, with Templin Gardens steps at right and Tower Street Bridge in the distance.

136. (Top) The reverse angle of #135 above.

(Bottom) Those anglers have gone right down to the River’s edge via the Templin Gardens steps.

137. On the most prominent site in Fergus sits St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church (1862) on St. George Street West at Tower Street North. For the Scottish majority population of the town, this was the chief place of worship. It’s made of limestone in Gothic Revival style.

138. The Kissing Stane, Tower Street North.

This granite boulder was uncovered when the plot below St. Andrew’s Church was cleared. After a bandstand was constructed here in 1870, it became a popular gathering place, the one place in town where public displays of affection were tolerated. To be kissed while sitting on the stane was supposed to bring good luck. The stane’s top surface has holes drilled in it, as there was once a plan to blast it to fragments with dynamite so a new bandstand could be constructed on the site. Fortunately for local lovers, the plan never came to fruition.

139. The view down Tower Street North toward the River. The Tower Street Bridge over the Grand is just after the traffic lights. The tower on the right is that of Melville United Church.

140. The whirlpool looking upstream from the Tower Street Bridge. Of all the settlements through which the Grand flows, only Elora can match Fergus for picturesqueness.

Let’s leave downtown Fergus and follow the Grand westward.

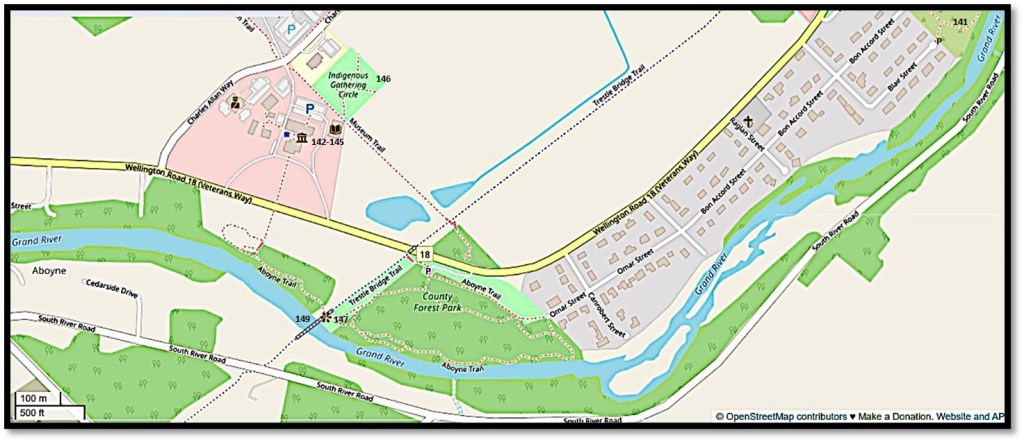

Map 13. West of Fergus

P at the end of Blair Street for the Arboretum.

P at the lot off Wellington Road for the Aboyne Trail and the Trestle Bridge viewpoint.

P at the large lot behind the Museum for both the Museum itself (admission by donation) and the Indigenous Gathering Circle.

141. The Grand River Arboretum, on the west bank of the Grand at Beatty Line on the western edge of town (see Map 12 above), offers a pleasant there-and-back stroll through what is essentially a strip of wild forest next to the River.

142. This striking Italianate Revival style stone edifice at 536 Wellington Road on the western edge of Fergus is the Wellington County Museum and Archives. It was built in 1877 as a House of Industry and Refuge, namely, a government-funded poorhouse. It took in the most vulnerable in society – the elderly, the infirm, the destitute, the mentally ill, orphans, single mothers abandoned by their partners. The abler inmates would work in a farm onsite in exchange for bed and board. Given that previously the homeless of Wellington County would be housed in jail for the winter months, it’s an example of the relatively enlightened Victorian social safety net. In 1947 it became a “home for the aged,” but this closed down in 1971. The building was converted to a museum in 1975, and is very much worth a visit.

143. The Museum contains moving photographic displays documenting the inmates of the House of Industry during its heyday.

144. A sequence of displays in the Museum showing the (not-quite-unanimous) affection of Wellington County for the British Royal Family.

Top: a photo of the Duke and Duchess of York, i.e., the future King George VI (dad) and Queen Elizabeth (mom), holding the future Queen Elizabeth II in 1926.

Middle: Flag commemorating the Coronation of George VI and Elizabeth in 1937.

Bottom: Sticky notes posted around a photo of the recently deceased Queen. The vast majority bear positive messages – “BEST QUEEN EVER” – though one or two beg to differ – “SHE STOLE OUR KOHINOOR, WEALTH AND HAPPINESS.”

145. A display in the Museum memorializes the First Nation known variously as the Attawandaron (as the Hurons called them), la Nation neutre (as the French called them) or the Chonnonton (as they called themselves). They were an Iroquoian longhouse-dwelling people who occupied the territory “Between the Lakes,” including the valley of the Grand River, until the mid-17th century. Their English name “Neutrals” derives from their attempt to stay neutral in the Beaver Wars between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Five Nations (backed by the British and Dutch) to the south of them and the Hurons and Algonquins (backed by the French) to the north.

The cause of the conflict was the Five Nations’ desire to monopolize the lucrative fur trade with Europeans. The result was the Neutrals’ obliteration in 1650-51, with any survivors probably being assimilated. The Neutrals had been previously weakened by famine and European-introduced diseases. Their disappearance left the valley of the Grand depopulated, though their archaeological remains are plentiful. The general ignorance of the geography of the Grand watershed at the time of the Haldimand Proclamation (see above #117) is chiefly because its original inhabitants were no longer around to act as guides.

146. The recently established Indigenous Gathering Circle (2023), behind the Museum.

“With pathways revolving around a circle [top] with three, upright granite stones representative of Métis, Inuit and First Nations [middle], the gathering area is intended for teaching, ceremonies, growing sacred medicines – including tobacco, cedar, sage and sweetgrass – and for the community at large to gather on a journey of reconciliation.” Jordan Snobelen, Wellington Advertiser (28 April 2023). Tobacco [bottom] is “the first medicine. It’s the medicine that precedes all other medicines … Whenever we’re planting anything or harvesting anything we lay down tobacco. We send our prayers into it … the intent is that it is a medicine of gratitude.” Amber Holmes, quoted in Keegan Kozolanka, EloraFergusToday (21 June 2023).

147. On the other side of Wellington Road from the Museum is the Aboyne Trail, a forested loop on the east bank of the Grand. It intersects with the Trestle Bridge Trail, so you can view this giant ex-railway bridge from underneath, then visit the top of the bridge and enjoy the fine view over the Grand.

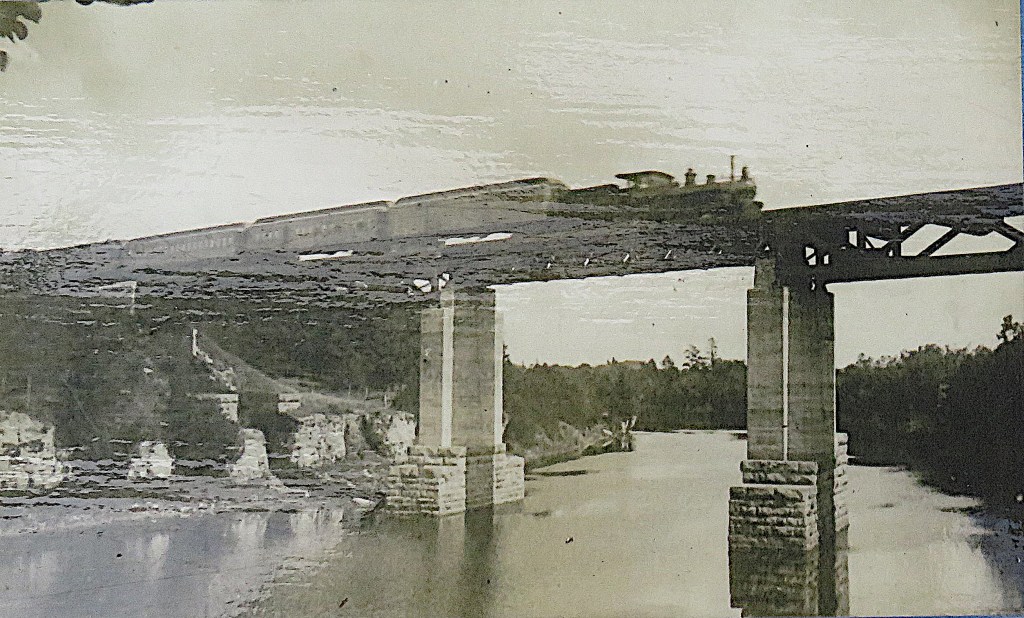

148. This is the third bridge on this site, constructed in 1909 for the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR). Its piers are of the then new miracle building material, concrete, and stand on stone plinths in the river.

In the 19th century, the GTR was the dominant rail system in Canada, with its national HQ in Montreal, corporate HQ in London, England, and several branches into the USA. But its financial difficulties increased in the early 20th century and it was absorbed into the Canadian National (CN) system in 1923. Several former Grand Trunk lines are still active today, but not this one: the line from Palmerston to Guelph via Fergus was abandoned by CN in 1989.

149. (Top) The view downstream from the Trestle Bridge.

The Grand in summer is so shallow in places that the angler (top centre and bottom) is in no danger of getting his socks wet.