Elora and Fergus are fraternal twins, born almost simultaneously, and located barely 6 km apart along the Grand River. Elora (about 8,000 permanent residents) is smaller than Fergus, but its population during the months of clement weather is swollen by hordes of tourists. That’s because the Grand through Elora is our river’s most spectacular stretch and Elora has learned how to exploit its own picturesque charms. It was crowned the “Most Road Trippable” town in Canada in 2019, and after the pandemic its accessibility is proving to be irresistible to day trippers. Elora is about 1 hour 40 minutes’ drive from Toronto, just over an hour from Hamilton, 40 minutes or so from Kitchener-Waterloo, and a mere half an hour from Guelph.

Aside from its trippability, the key to to Elora’s popularity lies just west of the town centre. That’s where the Grand is joined by a major tributary, Irvine Creek, and down each of the three branches of their Y-shaped junction the rivers flow through deep wooded gorges.

There are advantages to postponing your visit to Elora until late fall or winter: the crowds will have thinned, and so will the deciduous vegetation, affording you better views into the gorges.

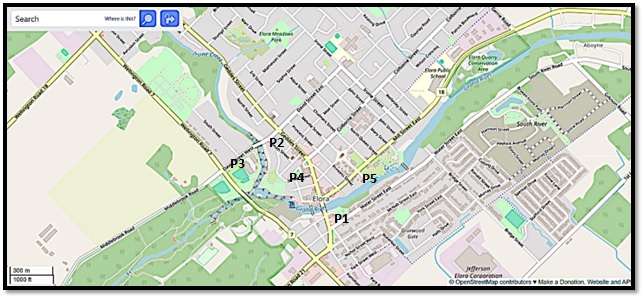

Map 14A. The Grand River through Elora, with free parking places (P) marked.

Downtown Elora is compact and there are enough things to see and do to keep you occupied for a day, including lots of quirky independent stores, bars, and restaurants. There are several places to P for free and, if you prefer not to walk far, you can drive between them to cover all the locations I mention here. If you don’t mind walking a few km, P at any one of these places.

As it’s the Grand River and its tributary Irvine Creek that are our focus here, you’ll want to check out the views from the five bridges. For the Metcalfe Street bridge and the pedestrian bridge just west of it, P1 at the municipal lot on Metcalfe Street just south of the LCBO. For the David Street bridge, P2 at the roadside on Smith Street. There’s no good place to P very close to the Wellington Road 7 bridge, so P3 roadside on David Street West near its junction with Wellington Road 7.

P4 at Hoffer Park and walk the short distance into Victoria Park to view the Falls, the “Tooth of Time,” and the gorge from the top of Lover’s Leap. If you are relatively fit and have footwear with gripping soles (essential in wet or icy conditions), you’ll definitely want to descend the steps in Victoria Park to Irvine Creek so you can check out the gorge at river level. P5 at Bissell Park at the south end of Melville Street to check out the Grand east of the town and the view from the footbridge at the end of Mary Street.

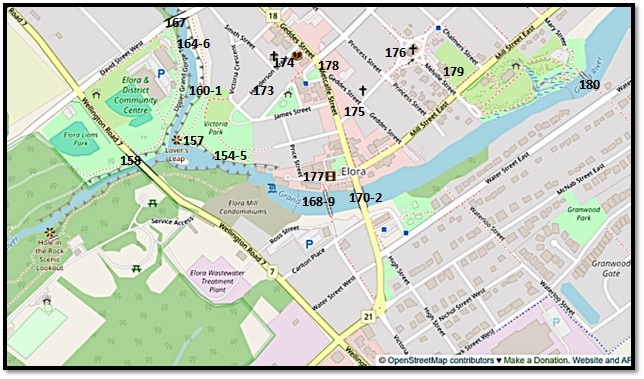

Map 14B. Central Elora in close-up, with sites numbered according to entries below.

150. Elora was founded by Capt. William Gilkison (1777-1833), a merchant seaman from Irvine, a port town in Ayrshire, Scotland. (That’s how Irvine Creek got its name.) In 1832, he purchased land in Nichol Township from the widow of Rev. Robert Addison of Niagara (see #121 above). Gilkison probably called his proposed settlement Elora because he liked the sound of the word, and/or because of the caves in the gorge. Ellora with two “l”s was the name of his brother’s ship, itself named for a famous cave temple complex in India. Gilkison didn’t live long enough to enjoy his investment: he died of a stroke in April 1833.

Let’s begin at the mill. Elora’s raison d’être was its location by a falls on the Grand where a mill could take advantage of water power. The eight-storey stone building above is not the original mill on this site. A wooden sawmill was built by Gilkison in 1832 but it and its successors burned down. This stone building was constructed in 1859, and was later known as Drimmie’s Mill. Together with a former whiskey distillery, granary, coach house, and villa, it was saved from dereliction by Pearle Hospitality. In 2018 they opened it as the Elora Mill Hotel and Spa, where these days you’ll be lucky to get a room for under $1,000 per night. The buildings of the old mill complex have been nicely preserved and (for the most part) sympathetically adapted.

151. The painter A.J. Casson (1898-1992), the youngest and longest lived member of the Group of Seven, is closely associated with Elora. He first visited in 1929: “I fell in love with Elora at first sight. It was a beautiful, old village in which nothing had been modernized. Despite having a mill, a furniture factory and a plough and harrow works, it was a quiet, sleepy little place. The only traffic was an occasional car or farmer’s wagon. It was the village that attracted and fascinated me. Elora was unlike any other Ontario town I knew. The others tended to be built on flat land, but Elora had a hilly terrain and was perched right on the lip of the spectacular Gorge. I became obsessed with sketching it” (7). This was the mill as Casson depicted it in 1930.

152. What would Casson think of the view today from the former Victoria Street Bridge? That huge development on the other side of the Falls is the Elora Mill Condominiums. They have only recently been completed and the 136 units are now for sale “from $1.2 million.” Further extensive developments on the south bank next to the condos are planned.

You can’t object to the revitalization of Elora. But really, is this condo building architecturally worthy of its setting? And doesn’t it represent the monopolization of a scenic spot by private interests? Elora’s most iconic site is now difficult to view unless you have an riverside apartment in the condo or are dining in the hotel.

153. On the old mill side, a three-storey cantilevered glass box extends over the Falls, giving restaurant diners a wonderful view of Elora’s icon, but blocking that view almost entirely for the public.

154. To see what I mean, go into Victoria Park and follow the black fence on your left until you come to a gap in the vegetation. (The gap is larger in the winter months) …

155. … then look back. That’s Islet Rock, now more usually known by the poetic name, “The Tooth of Time.” It sits midstream in the Falls, and its less photogenic rear end has been shored up with concrete so that it doesn’t wash away … not in the immediate future, anyway.

156. This is what Islet Rock looked like before the recent condo-ization of the spot.

157. As you continue along the fence in Victoria Park you come to the Lover’s Leap viewpoint. But to actually see the impressive Lover’s Leap rock in relation to the river junction, you have to stand somewhere entirely different …

158. … you need to be where that guy is who’s walking the dog across the Wellington Road 7 bridge over the Grand downstream.

Is this confusing? Well, be resolved to check out the views in all directions from each of the five bridges in Elora, and you won’t miss much.

159. This is that view up the Grand from the Wellington Road 7 bridge (top), with Lover’s Leap (close up, bottom) marking the spot where Irvine Creek, at left, joins the Grand. There’s a romantic tale of the suicide of a heartbroken Indigenous maiden associated with this spot, but it’s almost certainly mythical. As Mark Twain cynically put it in Life on the Mississippi: “There are fifty Lover’s Leaps along the Mississippi from whose summit disappointed Indian girls have jumped.”

160. Next, descend these steps in Victoria Park …

161. … and you’ll find yourself at the foot of the Irvine Creek gorge, if not quite at the water’s edge.

If you have any interest in geology, check out Kenneth Hewitt’s Elora Gorge: A Visitor’s Guide, which explains in great detail what you’ll see: ”About 40 metres beyond the steps the rockwall bulges out 3 to 5 metres. This imposing overhang is the re-excavated underside and an exposed flank of one of the larger reef masses. Close inspection will reveal interlocking colonies of Stromatoporoids or stroms, the main organisms that built the reef” (40). To clarify: the rock forming the overhang is dolostone of the Guelph Formation, a type of Silurian limestone made of 410-million-year-old fossilized organisms, the Stromatoporoids or stroms, which were a kind of sea-sponge that built reefs. These reefs, fossilized over the millennia, resist erosion from the rivers better than the softer limestone that underlies them, hence the overhangs that characterize the gorges here in Elora.

162. However, while these rocks may be hundreds of millions of years old, the gorges are much more recent. The Grand River as it is today only began to take shape when the Laurentide Ice Sheet melted at the end of the most recent Ice Age, a mere 15,000 years ago. And that’s when the river began cutting its way through this rocky area.

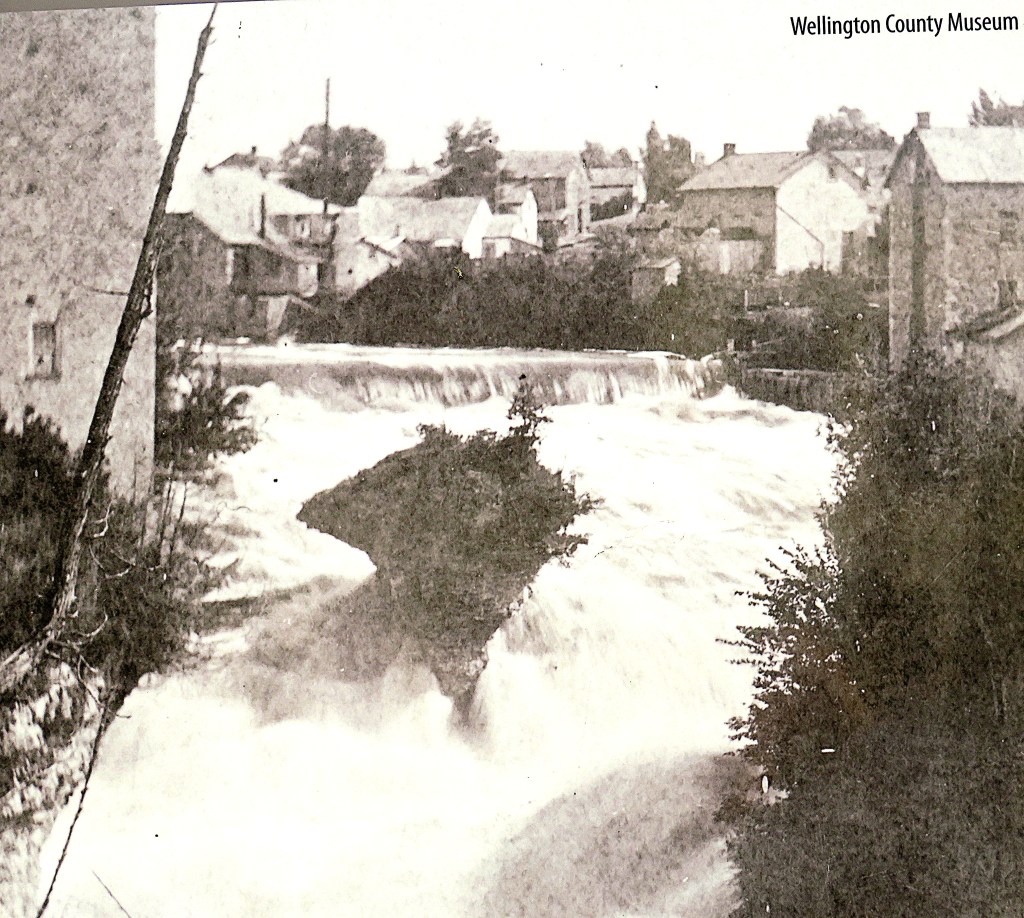

The Grand drops 352 metres from source to mouth over the course of its approximately 300 km length. This makes for a leisurely descent of on average just over one metre per kilometre. But the riverbed in the Elora Gorge is much steeper: here the average drop is about 5 m/km. High rocky walls contain the river and there’s no flood plain to relieve the pressure. So the erosive capacity of the river is much greater here. You can see the power of the Grand in action at Elora Falls above. It’s cutting away the softer rock beneath the harder reefs and leaving the overhangs typical of this area.

Now that the Grand’s tendency to flood has been controlled by the various dams upstream, the erosion has been slowed. But not by much at this spot. Sooner or later, the Tooth of Time will be … extracted.

163. From the foot of the stairs you have quite a scramble to get down to the Irvine itself, before mounting the midstream rubble to get that perfect Instagram shot. Those big rocks in the creek have almost certainly fallen when the overhangs on the cliff have been sufficiently eaten away beneath.

164. Looking downstream in the Irvine Gorge. The creek’s shallow enough at the moment that you could walk down the middle of it if you had waterproof waders.

165. Caves on the left bank of the Irvine Gorge below the David Street bridge. Pockets of the softer limestone beneath the fossilized reefs have dissolved away in high water over the years.

166. Follow the Irvine a short way upstream from the foot of the stairs, and you come to this, the classic view of the David Street bridge from below. Bridging the Irvine was quite a problem in the early days, given that the gorge here is 50.2 m (165’) wide and 21.3 m (70’) deep. The first bridge here was built in 1847 by two young carpenters who ingeniously managed to bridge the chasm using only the trunks of tall elm trees. The result was supposedly the first cantilevered bridge in North America. Of the $400 payment they received, they cleared only $20 after they had paid off the workmen who’d helped them.

The current bridge, the seventh on this site, was built in 2004. It’s an open spandrel deck arch on a central masonry pier, and is a replica of the bridge as it was in 1921, reusing the central pier of the second bridge here (1867). At that time the Irvine Gorge had been practically clear cut and used as a garbage dump. Only in the later nineteenth century did cleaning up and reforesting begin to take place.

From the staircase you might be tempted to go in the other direction (downstream) towards Lover’s Leap at the junction of the Grand and Irvine. But unless you have waders, you’ll find it very difficult going, even when the water level is low. And anyway, thanks to the overhang you won’t be able to see much of Lover’s Leap from right below it.

167. The Irvine Gorge from the David Street bridge.

Now let’s check out the bridges in downtown Elora.

168. This is the pedestrian bridge, on the site of what used to be the Victoria Street vehicular bridge. Early settlers had big problems bridging the Grand here, even though there’s no gorge to negotiate. Roswell Matthews and his family, originally from New England, were the first white settlers in 1817, some years before Gilkison purchased the district. At that time the country between the Grand here and Lake Huron was, as far as anyone knew, completely uninhabited. Matthews’ attempt at bridge and dam building failed whenever the Grand went into flood. The Matthews lasted nine years on the site before giving up.

The first permanent Victoria Street bridge was built in 1842, and there were four incarnations until it was closed to vehicles in 1969 and to all traffic in 2005. This pedestrian bridge was built in 2019 on the original stone piers of the Victoria Street bridge.

169. The view from the footbridge over the Drimmie Dam and Falls exposes the reinforced backside of the Tooth of Time.

170. Only 80 metres upstream is the Metcalfe Street bridge, which now carries all the vehicular traffic in and out of downtown Elora. The metal truss Badley Bridge was replaced in 2020 with this rather bland but undoubtedly sturdier concrete structure.

171. Two contrasting riverscapes downstream as viewed from the Metcalfe Street bridge.

Top: the not quite completed condo dominates the view of the south bank.

Bottom: picturesque old stone buildings with balconies on the north bank. “Because the village is a place of cliffs, it’s interesting to see that when settlers began building they created another kind of cliff … habitations producing a visual effect similar to the one created by the towering and over hanging stone walls of the gorge” (Brandis, 58).

172. The view upstream could hardly be more different. Before its plunge into the gorge, the Grand seems placid, its north bank quite domesticated.

Now let’s look around the town itself.

173. One of the oldest dwellings in town is the Old Maclean House at 17 Henderson Street. In Ontario vernacular one-and-a-half-storey style, it was built of split fieldstone in 1858 for the headmaster of Elora Grammar School.

174. Farther east on Henderson Street is St John Anglican Church, built 1875 in red brick Gothic Revival style. Knitted and crocheted poppies cascade from the steeple to mark Remembrance Day.

A former rector of an earlier incarnation of this church, John Smithurst (1807-67), is famous hereabouts for his unrequited love affair with Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), the nursing pioneer. The story of this affair, which is almost certainly as mythical as the suicidal leap into the gorge of the disappointed Indian maiden, has its basis in a silver communion set owned by the church that was supposedly a love-gift to Smithson from Nightingale. In fact, it’s almost certain that Smithson and Nightingale not only never met but also had nothing whatever to do with one another. But that hasn’t stopped the endless elaboration of the pair’s “romance,” and there are stained glass windows in this church commemorating both “lovers.” For more on this, see Rev. Eric R. Griffin.

175. Street art in Church Street East.

Mermaid in Elora (top) is a gift shop with eclectic items from all over the world. Its entrance is around the corner on Metcalfe Street, in a house built in 1869 to house the Elora Observer newspaper.

(Middle) some of the seven doors arranged along the Church Street East side of the building form a colourful display around Thanksgiving.

The Clock Tower (bottom) is an installation (2018) constructed by several local artists using old machine parts.

176. Knox Presbyterian Church in Gothic Revival style stands prominently on a quiet traffic island at the intersection of Church East and Melville Streets. The congregation was founded in 1837 in a log church. This later edifice, of stone brought in by rail from Guelph, was finished in 1873 at the then immense cost of $22,000.

177. Scenes around the Old Mill.

Top: part of the mill complex looking down steep Price Street.

Middle: the front elevation of the mill.

Bottom: the stone streetscape of Mill Street West

178. A prominent building on Metcalfe Street, the main drag in Elora since the opening of the bridge, is Gordon’s Block. It was built in 1865 at the acute-angled junction of Metcalfe and Geddes Streets. The larger part of this block was first occupied by the Dalby House, a hotel, later called The Iroquois. Only the “peak” of this flat-iron-style building was occupied by the business of harness maker Andrew Gordon. But Gordon, who didn’t get on with Dalby the hotel owner, managed to get one up on the latter by placing that plaque announcing GORDON’S BLOCK high on the tip of the building.

179. Elora’s connection with the visual arts has been strong since A.J. Casson’s day. The Elora Centre for the Arts on Melville Street is a gallery, studio/classroom, and shop in the process of being greatly expanded. Entry is free and there’s always something of interest to see. I was struck by these colourful “Seaweed Portraits” by Gitte Hansen. They’re photographs of seaweed, digitally printed on canvas.

180. East of downtown Elora, you reach the footbridge and Bissell Dam (top and middle) by the boardwalk in Bissell Park. (Bottom) the view downstream from the footbridge on a calm evening.

Bissell Park is named for the factory that once stood on this spot producing disk harrows, set up in 1901 by Torrance E. Bissell. The dam was constructed in 1909 to provide both water and hydroelectric power for the factory. The firm ceased business in 1955 and the factory was demolished a decade later. See Stephen Thorning, “Bissell Park Once Site of Farm Implement Factory.”

The above scenes have something of the quality of René Magritte’s “Empire of Light” sequence, don’t you find?