Map 15A (left): the Elora Gorge Conservation Area (CA) according to OpenStreetMap. The CA is bounded by the thick green line, which continues onto Map 16 below. Numbers refer to entries below. Maps 15A, 16, and 17 courtesy of OpenStreetMap and Its Contributors.

Map 15B (right): the same area as mapped by the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA).

For more than 3 km downstream from Wellington Road 7, the Elora Gorge CA encloses the Grand River. That is, literally encloses: there’s a high fence around almost all of it. During the season, 1 May to 15 October, you enter the CA by car at the Gatehouse and pay the appropriate fees. The rest of the year, the CA is closed. That’s right: for six and a half months, there is no public access to the extensive southern section of the beautiful Elora Gorge.

The reason has to do with the changed role of Ontario Conservation Authorities. These began as organizations intended to manage water resources to protect people from flooding and to ensure the purity of their drinking water. But as a result of severe provincial government cuts, they have increasingly been expected to “pay their own way,” raising the bulk of their operating budget from user fees and charitable donations. A very popular site like Elora Gorge has become a cash cow. It makes so much money for the GRCA in the season that it’s not worth keeping it open for the occasional nature lover or dog walker during the rest of the year. After all, hiring security to protect all that valuable infrastructure from vandalism during the off season would be quite an expense.

There are currently 604 campsites in the Elora Gorge CA. In 2024 it cost $8.50 per adult and $3.75 per child under 13 just to enter the CA, from $49.50 to $66.00 per night for a campsite depending on service level, plus $17 per vehicle overnight parking fee. With taxes, most families of mom, dad, and two kids paid well over $100 per night to camp. If they wanted to go tubing down the Grand, that was an additional $54 per person plus a returnable $75 p.p. security deposit.

Map B reveals that almost every inch of the usable area around the Elora Gorge in the CA has been given over to recreational activities: campsites, rentable pavilions, picnic areas, showers, splash pads, food and tubing concessions, all linked by a dense network of paved roads and parking lots.

If you are a hiker who wishes only to commune with nature, then the Elora Gorge CA is not for you. Instead, descend the steps in Victoria Park to visit the Irvine Gorge (see #160-166 above) while you can still do so for free.

What will you miss in the Elora Gorge CA? I’ll tell you, as I went there in season so you don’t have to.

181. Wander the trails while the Elora Gorge CA is open, and you’re likely to spot plenty of this sort of thing: giant green ambulatory Life-Savers (get it?) heading for the start of the tubing run.

You have a choice at this bridge: west or east bank? An easy one, as only the east bank along the Gorge has a trail with scenic lookouts.

182. A security guard checks her phone at the riverside access point where the tubing run (about 2 km long) begins over on the west bank of the Grand. That’s a large first aid kit on the ground beside her. Aside from being costly, tubing can be hazardous … but that’s its appeal, right?

183. As the northern section of the Gorge in the CA is narrow, its sides are steep, the trail runs along the top edge, and there are leaves on the trees, there are actually very few places from which to glimpse the River.

184. The roots of ancient cedars clutching solid rock put on a good show along the trail.

185. The highlight on the east bank trail is the Hole in the Rock. A steel staircase leads down to the riverside through a hole in the rocky side of the Gorge. Based on a photo of around 1900, the heart-shaped cavity best seen from the foot of the stairs (upper left top and bottom) is the so-called Wampum Cave. In 1880, David Boyle (1842-1911), the Scottish-born pioneer of Indigenous archaeology, was the principal of Elora Public School. The story goes that inspired by his teachings, two of his pupils found some wampum in this cave, which Boyle identified as a relic of Neutral Indians fleeing the Beaver Wars of the mid-17th century. Boyle moved to Toronto in 1883 and by the turn of the century was the superintendent of the Ontario Provincial Museum and considered Canada’s preeminent archaeologist. The wampum and many other artefacts collected by him can be found in the David Boyle Room at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. For more on Boyle, see Stephen Thorning, “Elora’s David Boyle.”

186. Your hike along the eastern rim of the Gorge ends abruptly at the steel fence that bounds the CA along Wellington Road 7. You turn around here and walk back the way you came. I shall make no comment about the unofficial gap in the fence that greeted me when I reached this point, except to say that I was not surprised.

That’s it for the Elora Gorge CA in season.

187. It’s now mid-December and the CA is closed to all visitors. Drive down Middlebrook Road following the course of the Grand, P roadside on 3rd Line West, then cross Middlebrook Road. There you’ll see this white blaze and diamond-shaped sign indicating that, in the off-season, this is an access trail to the southbound Grand Valley Trail (GVT). (When the CA is closed, the GVT Trails Guidebook directs northbound hikers from here up Middlebrook Road. You should be aware that this is a hazardous route for pedestrians as this road into Elora has no sidewalk or defined shoulders.) This access trail runs along an outside edge of the CA, with its southernmost campsite just behind the trees on the left …

188. … and this pickup truck on stilts parked by a house on the right.

189. There’s not much avian activity on this winter day, except for this chubby junco who seems to be keeping a low profile. I’ll soon find out why.

190. The GVT is broad and pleasant …

191. … and don’t tell anyone, but it connects seamlessly with riverside trails in the CA. I go north as far as the bridge flush with the River that marks the tubing run exit. There’s not a soul around …

192. … as I take this photo of the Grand upstream from that low bridge. I could continue northward along the trail on either bank from here, but I’m conscious that, technically, I’m trespassing. (I say technically, as I have not passed any sign to indicate that I’ve entered forbidden territory.)

193. The Grand is low, but it’s flowing freely for mid-December, with little sign of ice.

194. Now I turn 180° and head downstream. Though this is still GVCA territory, soon I’m no longer even technically trespassing, as according to Map 12 of the GVTA Trails Guidebook I’m legitimately on the all-season Belwood section of the GVT. Some distance away, there are some tall bare trees, and on one of the branches, I see a black dot. I use my camera to zoom in on it …

195. … and closer in …

196. … and now the 50x optical zoom on my Canon PowerShot is operating at its absolute limit. I’m lying on the ground to reduce hand tremor and taking lots of shots in the hope one or two will be more or less in focus. And one or two are. I’ve caught a bald eagle surveying the Grand beneath in as majestic a pose as is ever found on flag or crest. As this is a protected bird, I won’t reveal the precise location I saw it, just note that my sighting was on 16 December 2023. In Ontario, bald eagles have made something of a comeback from endangered status in recent years. Earlier in 2024, the nest of a pair was sighted in an undisclosed location in Toronto, of all places.

Time to leave the Elora Gorge CA, return to the car, and head downstream.

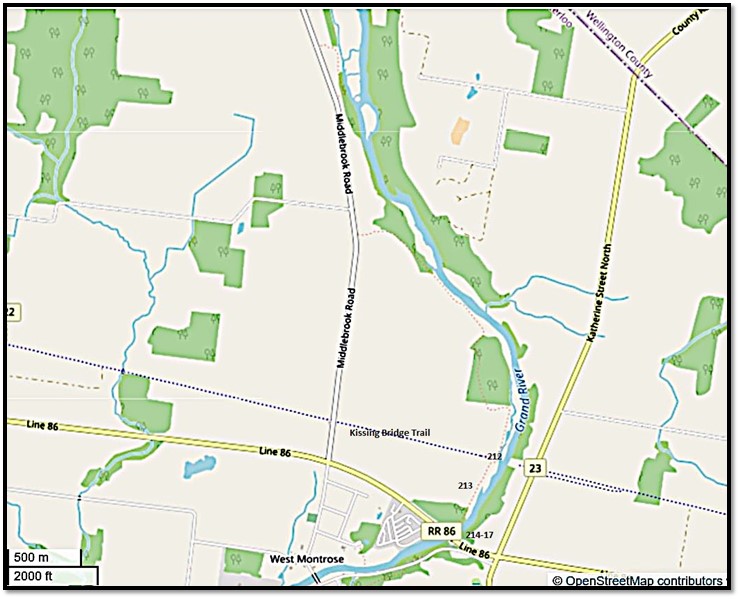

Map 16. Elora Gorge CA to Middlebrook Bridge and beyond.

197. This is Pilkington Overlook, a high spot on Wellington Road 21 between 6th and 8th Lines. There’s a small P and views west over the valley of the Grand. In December, the panorama is better than when the trees are in leaf, but the muddy trails lead nowhere in particular.

198. There’s a not very pleasant story behind the Pilkington name. Robert Pilkington (1765-1834) was a British military engineer, rising eventually to the rank of major-general. He trained at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, the name coincidentally given in 1822 to the Township south of here, which it still bears. Pilkington came to North America as a lieutenant in 1790 and was involved in several important construction projects in Upper Canada, including the first government house in York (later Toronto), where he befriended Lieutenant Governor Simcoe and his wife. He returned to England in 1802 and never set foot in Upper Canada again.

However, soon after his return to the UK he bought the strip of land at the north end of Block 3 of the Haldimand Grant, the full 12 miles across and containing 15,000 acres. Needless to say, Six Nations received nothing from this transaction, as Pilkington bought it from a previous purchaser, William Wallace, who had already defaulted on what he owed to the Mohawks. On this land Pilkington apparently planned an ambitious settlement. However, “it is said he signed the agreement without having seen what he was buying. He seems to have made no attempt to speculate with it, but he took a childish delight in talking about his estate and he boasted about the mansion he intended to build there for his old age” (Dunham 110). The “estate” was of course completely undeveloped wilderness.

Pilkington then promised 100 acres of free land in that “estate” to any English families who paid their own way across the ocean and settled it. Twelve families from the Midlands took up the offer, enduring the hardships of an Atlantic crossing and then the arduous trek into the bush. Some of them managed to link up with Roswell Matthews, the pioneer at what is now Elora (see #168 above), only to discover that Matthews, who had received a similar promise from landowner Thomas Clark, had never received any title deed. When Pilkington died in 1834, the settlers were told he’d left no mention of any Canadian land in his will, so they had no claim to it. Unable to afford the government’s offer to buy the land at four dollars an acre, they had no choice but to continue to squat and struggle to maintain themselves, cursing Pilkington for his false promises. Their children, faced with the prospect of inheriting nothing but trouble, moved away as soon as they were old enough.

199. The next place to get close to the Grand is at Wilson’s Flats. The map posted there shows that this is #4 of the 33 official access points on the River for boaters.

200. You reach the P at Wilson’s Flats by turning right off Wellington Road 21 onto 8th Line East, and continuing for about 500 metres. 8th Line is the road visible above; it crosses the Grand on a modern concrete bridge just off to the right. If you continue in the same direction (NW) for about 3 km, 8th Line meets Middlebrook Road.

After the drama of the Gorges, these Flats may seem anticlimactic, but they have their appeal. Here the Grand has opportunity and space to spread out when at flood, scattering nutrients over a wide area.

201. The Grand in December here is back to being a creek. That’s the Pilkington Overlook at back, so this is the reverse angle of #197 above.

202. There’s a tall pole by the bridge over the Grand (top), holding a platform supporting a raptor’s nest. Not of a bald eagle in this case, but of an osprey, that is, a large hawk specialized in catching fish by diving into water talons-first.

“Osprey nests are built of sticks and lined with bark, sod, grasses, vines, algae, or flotsam and jetsam. The male usually fetches most of the nesting material … and the female arranges it. Nests on artificial platforms, especially in a pair’s first season, are relatively small – less than 2.5 feet [76 cm] in diameter and 3–6 inches [7.6–15.2 cm] deep. After generations of adding to the nest year after year, ospreys can end up with nests 10–13 feet [3–5 m] deep and 3–6 feet [91 cm–1.8 m] in diameter – easily big enough for a human to sit in.” (Cornell Lab). This female osprey seems to have artfully decorated the outside of her nest [bottom] with fragments of multicoloured fabric. In it she’ll lay 1 to 4 eggs with an incubation period of 36–42 days. See my picture of an osprey by the Niagara River here.

203. There are only short dead end trails from the P at Wilson’s Flats. But if you continue up 8th Line a little way, there’s a small P on the right. And here you connect again with the GVT. It runs dead straight in a NE direction through a wooded area …

204. … and then you find yourself at the riverside for a short stretch. Keep going upstream from here and you’ll soon find yourself back in the Elora Gorge CA.

205. Days are short in mid-December. Better get back to the car before it gets too dark to see where I’m going!

206. Next stop (it’s now late fall) is on the Woolwich-Pilkington Townline (a.k.a. Weisenberg Road/Township Road 60) that separates Centre Wellington in Wellington County from Woolwich Township in Waterloo Region. It’s Middlebrook Bridge … or rather, ex-Bridge. When you approach from the west, this is what you see. Sealed with a brutal steel barricade that’s ironically daubed with floral graffiti, the bridge is closed not only to motorized vehicles, but also to pedestrians and cyclists.

207. A laminated flyer is attached to the bridge. When I visited Facebook via the QR code and did an Internet search, I found that this bridge is the object of an impassioned debate that has lasted several years. It seems the bridge has become “a wedge instead of a link” for the surrounding community, as one reporter aptly put it (Shuttleworth). The Arch, Truss & Beam heritage bridge inventory gives the following information about what it calls Chamber’s Bridge: “The one-lane, timber deck, camelback Pratt through truss was built in 1930 by an unknown builder and engineered by Herbert J. Bowman. It is believed that the superstructure was brought to the Grand River from another location in 1946. … Several other bridges have been located at this crossing prior to the current bridge, the first as early as 1845. Knowledge of these previous structures helps to explain the superfluous pier that is not structurally necessary for supporting the current bridge but may indicate a previous double-span bridge. In a 1906 Atlas, the bridge was seen located next to John Chamber’s land. This is probably why it was named the ‘Chamber’s Bridge.’ The structure is also part of the Grand Valley Trail, which travels along the west end [sic] of the Grand River and crosses the bridge. In 1994, the bridge was deemed unsafe and closed to both vehicles and pedestrians due to its deteriorating deck and rusting steel supports. This resulted in an eight-year closure of the bridge between 1994 and 2002. The bridge underwent repairs and is now open to the public with a posted load limit of three tonnes” (Benjamin 178).

But this report is from 2013, more than 10 years ago. What’s going on now?

This bridge, whose maintenance costs are shared by Centre Wellington and Woolwich Townships, was closed to vehicular traffic in 2013. An environmental assessment on behalf of Woolwich was done in 2018. The bridge was found to be “in poor condition … with corroded stringers, rivet heads and bearings and a sagging surface.” (GM BluePlan). It was recommended that it be removed at a cost of about $550,000, and turn-around circles installed at the dead ends of the roads on both sides of the Grand. In January 2020 both Wellington and Woolwich councils agreed to remove the bridge and not replace it. It was slated to be demolished in 2028, though why this relatively distant future date was chosen is unclear. Surely the two councils weren’t using the “demolition by neglect” strategy that developers use to evade pressure from heritage groups?

In April 2021 a steel blockade – “a zombie barrier” as one cyclist colourfully put it (Shuttleworth) – was installed at each end, sealing it off completely. In the meantime, a Save the Bridge campaign has grown to more than 3,000 members in what is a thinly populated rural area. As a result of their pressure, In October 2021 Centre Wellington council voted to reconsider demolition. Costs estimated the following month included: removal, $720,000; rehabilitation for pedestrian/cycling use, $1.6 million; and replacement for pedestrian/cycling use, $1.2 million.

On 23 February 2022 Centre Wellington Council voted once again to demolish the bridge. But on 1 August 2023, a newly elected council in Centre Wellington reconsidered demolition in light of the Save the Bridge campaign. However, a report on 30 October 2023 stated that “the bridge is continuing to degrade at a fast rate … most notably, steel stringers that the wood deck rests on have completely failed in the end bays, causing the wood deck to lose contact with the stringer top flanges” (Buckmaster). Since then, nothing much has happened. The steel blockades remain in place, the bridge has continued to decay, and the 2028 demolition date gets closer.

208. I want to view the bridge in relation to the Grand, but there’s no vantage point here from which to do so. I do manage to get a nice shot of the River downstream.

209. The Middlebrook Bridge may once have carried the GVT, but obviously it doesn’t any longer. Northbound, the GVT now strikes left from the bridge approach and follows the Grand for a few hundred metres until it cuts cross-country to meet 8th Line. This is a challenging section of the trail, and a frustrating one if you hope to get a side view of the bridge. It’s just about possible, but you have to go off trail, cutting steeply down through brush and mud to the riverbank, and even then your view is likely to be incomplete. The shot above does make it clear that the central pier no longer touches, let alone supports, the bridge.

210. Returning to the bridge approach, I fall into conversation with a local gentleman. He explains that I have to go to the other side of the Grand to see the bridge in relation to the river properly. So I drive about 10 km, for that’s how far it is, via Middlebrook Road, 8th Line West, Wellington Rd 21, and Weisenberg Rd, to the bridge approach on the opposite bank. And though there’s a similar zombie barrier there, you can get a better view of the bridge’s wooden deck (top), then make an easy descent to the riverbank to see the whole structure in relation to the river (bottom).

211. There’s also a pleasant wooded trail with good access to the Grand on this, the east bank.

Probably the old bridge, thanks to deliberate official neglect, is now beyond saving. But the abutments and central pier look solid. Surely these can be retained to support a new lightweight span for pedestrians and cyclists? Without this bridge it’s now a 10 km drive instead of a two minute walk to cross the 50 metre wide Grand.

A bridge is rarely just a means to cross an obstacle such as a river. It’s often a connection between communities. And especially if motorized traffic is debarred, a bridge provides a quiet place to fish, or stop and chat, or merely pause to contemplate the flow beneath, which is also the flow of time. The pedestrian bridges in Fergus and Elora are successful structures because they acknowledge the spiritual function of bridges.

This bridge, on a townline, is a shared responsibility between two municipalities. It thus provides a chance for separate jurisdictions to work together to ensure that something is not replaced by nothing … or rather those two zeroes described by the proposed turn-around circles.

Map 17. The Grand River east of Middlebrook Road as it flows into West Montrose.

212. It’s winter again, and we’re on a short section of riverside GVT north of West Montrose, at the point where a former rail line used to cross the Grand. That line was the 127 km Guelph and Goderich Railway, built 1904-07 and abandoned by CP Rail in 1988. The former track has been removed and almost all of it turned into a rail trail. The section here through West Montrose is called the Kissing Bridge Trailway (KBT) – an explanation for that name is coming soon – and runs from Wellington Road 39 on the western outskirts of Guelph, through Elmira to Millbank. From there it’s a short hop to the start of the G2G Trail, which using the rest of the course of the former railway runs all the way west to Goderich on the shore of Lake Huron.

The abandoned pier in the image above indicates that hikers on the KBT cannot directly cross the Grand, because the rail bridge has been removed and been replaced by … nothing.

213. On the west side of the Grand in December stretches a vast field of mud. But in the growing season “one views magnificent, flat expanses of rich farming soil, and the distant profiles of barns on Mennonite farms” (Gingrich 52).

214. Soon we arrive at the foot of this bridge (top), which carries Wellington Road 86 over the Grand and into the nearby town of Elmira. As we shall see, there’s a good reason why most traffic should use this road to bypass the village of West Montrose. Hikers on the GVT must climb up to the level of the bridge (bottom), cross it and the road, and then walk down River’s Edge Drive into West Montrose. Hikers on the Kissing Bridge Trailway have an even longer deviation, via this bridge and Katherine Street North, in order to regain the KBT on the other side of the Grand.

215. Looking east, we’re approaching the junction at Zuber Corner. The blazes tell hikers on the GVT to climb that bank on the right as it’s a short-cut to River’s Edge Drive. The yellow diamond-shaped sign above it is one found frequently in this part of Wellington County. It warns motorists to be careful …

216. … of these vehicles. And (top) as luck would have it, one was passing me on the other side of Wellington Road 86 at that very moment. It’s an Old Order Mennonite horse-drawn buggy.

(Bottom) Road 86 has soft shoulders wide enough to accommodate the buggy, though the bridge over the Grand does not. The buggy’s owner makes a concession to present-day reality in mounting that rear reflecting triangle, essential to warn motorists at night, as the buggy is painted the traditional black.

Mennonites are a radical Protestant sect, now with many branches, but tracing their origin to Menno Simons (1496-1561), a Dutch theologian and former Catholic priest. They are anabaptists, that is, they believe that baptism can take place only when members are old enough to freely confess their faith in Christ. They believe strongly in community, in non-violence, and in resistance to the ungodly ways of the larger human world: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God – what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Romans 12:12). Persecuted in the German-speaking lands where most originated, they sought freedom in North America. Currently there are about 500,000 in the USA and 200,000 in Canada.

Of the Mennonites in Canada, the Old Order are a small minority. There are currently about 7,000 of them in Ontario, chiefly in the Waterloo area. They are the ones who, in the aftermath of a schism in the later 19th century, decided to continue to speak the German dialect known as Pennsylvania Dutch, to dress modestly, to resist modern technologies such as radio, TV and Internet, and to travel by horse and buggy instead of by motorized vehicles.

Mennonite presence in this area goes back a long way. This part of Woolwich Township was part of Block 3 of the Haldimand Grant, and had been originally purchased from the Mohawks by the improvident William Wallace (see #198 above). In May 1807, Wallace had sold 45,185 acres at a dollar an acre to the German Company, which was acting on behalf ot the Pennsylvania Mennonite community. Their representatives, Benjamin and George Eby, had come from Pennsylvania to view the lands already purchased by American Mennonites in the more southerly Block 2 west of the Grand. These Mennonites became enamoured of this more northerly, remote, undeveloped district around the Grand, which they began to settle. They were, and still are, highly experienced and productive farmers. As for Wallace, he would disappear, probably back to the USA during the War of 1812, after which his remaining land was appropriated by the government of Upper Canada.

217. The view downstream from the Wellington Road 86 bridge toward West Montrose. The village’s most striking feature – the most famous and precious of the hundreds of bridges across the Grand River and its tributaries – appears as a purplish strip in the distance. We’ll be getting much closer in the next episode.