“5.3.1 [Bridge] Maintenance Strategies

The best strategy is continual maintenance, rehabilitation and conservation,

which can preserve a bridge indefinitely” (Fontaine 103).

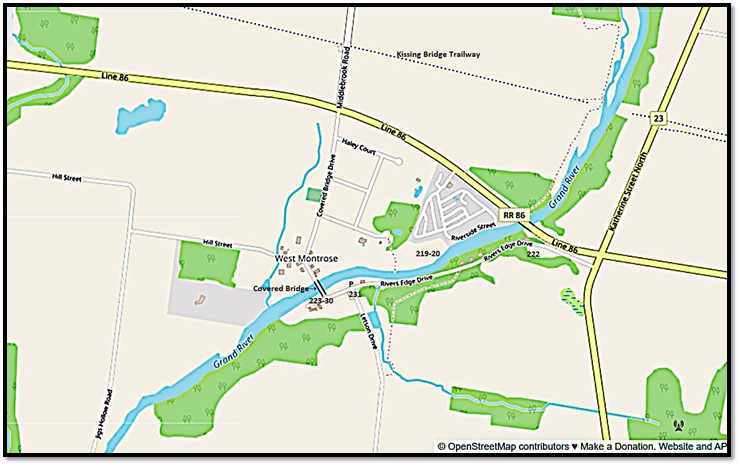

Numbers on the maps correspond to locations in the numbered entries that follow.

Map 18. West Montrose Covered Bridge and its surroundings.

218. We’re on River’s Edge Drive on the south bank of the Grand River approaching the village of West Montrose (pop. 245). Ahead is the most iconic – that overused word is apt here – of the hundreds of bridges across the Grand and its tributaries.

Bridges have a mainly positive role in human culture. They allow you to pass easily over otherwise formidable obstacles. They connect. If well-designed they may attain the status of civic icons: London’s Tower Bridge, San Francisco’s Golden Gate, Sydney Harbour Bridge. Few would disagree with the sentiment of the famous quotation, “We build too many walls and not enough bridges.” Look it up and you’ll probably find it attributed to superbrain Isaac Newton. Actually, it wasn’t Isaac Newton who said it, but Joseph Fort Newton (1876-1950), a Baptist preacher from Texas, and he didn’t phrase it quite so memorably. This is what he wrote in Adventures of Faith (1948): “Why are so many people shy, lonely, shut up within themselves, unequal to their tasks, unable to be happy? Because they are inhabited by fear, like the man in the Parable of the Talents, erecting walls around themselves instead of building bridges into the lives of others; shutting out life.”

Still, the Newtonian idea holds good. Building bridges is hard work and involves risk. So we tend to build too few of them, literally and metaphorically. And the ones we do build we immediately take for granted, even though a bridge will only stay in place for any length of time if it’s well-built in the first place and continually maintained from then on.

219. No, that bridge is no icon. it’s the modern one carrying Township Road 86 around West Montrose. Nondescript though it is, it’s had an important role in ensuring the survival of the iconic one. As we shall see.

The woman is exercising her dog on the flats across the Grand, but the dog is more interested in those geese than in its owner’s ball …

220. … and cannot resist the temptation to put the whole flock to flight.

221. On this side of the river one goose is unmoved. It’s late February and the Grand is flowing freely, but those icy chunks on the riverbank are a reminder of what all bridges over the Grand have to endure as winter comes to an end.

222. We pass the former West Montrose Public School, closed in 1966, now a private residence. It was built of fieldstone in 1874 and the school bell is still in place on the roof. On high ground on River’s Edge Drive about 1 km east of the village, it replaced a frequently flooded schoolhouse closer to the village centre. West Montrose, like all the settlements on the banks of the Grand before mid-20th century flood control measures, was used to periodic inundation.

223. Coyly at first, the West Montrose Covered Bridge comes into view. According to Arch, Truss and Beam (Benjamin), in 2012 in the Grand River watershed there were 678 bridges, of which 167 had heritage value, while 38 more with potential heritage value had been demolished. This bridge ticks all the heritage boxes. It’s a rare, early example of a construction method. It displays a high degree of craftsmanship and technical achievement. It has a direct association with a community and yields information that contributes to an understanding of that community. It reflects the work of an engineer who is significant to a community. It is important in defining the character of an area. It is historically linked to its surroundings. It is, in short, a landmark.

224. The original notice inviting contractors to tender. Why was a covered bridge required?

The short answer is that in 1880 in this rural area, wood from local trees was the default construction material, and wooden bridges last much longer – five times longer, or more – if their decks are protected from the elements by a roof. There are wooden covered bridges in Europe that have been around for centuries, such as the Kapellbrücke (i.e., Chapel Bridge, built ca. 1360, 205 metres long) in Lucerne, Switzerland. Of course wooden bridges are vulnerable to fire, and many in North America have been lost that way. The Kapellbrücke itself was partially destroyed by a fire in 1993. Many too have been swept away by floods and ice jams, though wooden bridges properly designed can be as resilient as ones made of stone, steel, or concrete. As many as 400 covered wooden bridges were built in Canada after 1800, though only a small fraction of them remain, including the world’s longest, the Hartland Bridge in New Brunswick, at 391 metres. A mere seven were built in Ontario in the 19th century, and this one at West Montrose, 62 metres long, is the last survivor.*

*It’s no longer the only covered wooden bridge in Ontario, however, as a lattice covered pedestrian bridge based on an early 19th century design was built across the Speed River in Guelph in 1992.

225. This bridge was designed and built by brothers John and Benjamin Bear in consultation with their father John Sr., a Mennonite minister. (The Bear family, whose name was originally Behr or something like it, originated in Switzerland and came as Empire Loyalists to Ontario via Pennsylvania.) The bridge, completed in November 1881, was constructed entirely of wood, specifically oak for the decking, white pine for the trusses and covering, and cedar shingles on the roof. In the measurements of the day it was 196 feet 6 inches long, 17 feet wide, and 13 feet high. The deck was of 3 inch oak planks with ¾ inch spaces so horse manure could fall through. The abutments were cedar cribs filled with loose stone, sturdy enough to defend the bridge against ice buildup and flooding. The central pier, now stone, originally consisted of 15 wooden piles driven to a depth of 12 feet. The sides of the bridge had 12 windows each, with permanently open slats to let in light and to improve the bridge’s wind resistance. These windows were used as fishing holes. Signs hung at the entrances read, “Anyone driving a horse-drawn vehicle through this bridge faster than a walk is liable to the full punishment of the law.” The bridge was painted in 1882 at a cost of $74.25. It’s unclear how long ago red paint was first applied. It soon became clear that the interior of the bridge needed to be lighted at night. So a contract was drawn up with a lamplighter, who in 1897 received $12.95 per year and had to provide lanterns, oil, and wicks himself. He’d fill the lanterns with coal oil and hoist them by pole onto hooks on the upper beams. In winter, the interior deck of the bridge had to be covered with snow by hand to make it passable by horse-drawn sleighs.

226. There were of course no motor vehicles in Canada in 1881. They didn’t start arriving until after the turn of the twentieth century.

227. The bridge’s wooden abutments were replaced by concrete ones some time after 1900. In 1904 the oak flooring had to be replaced. In the late 1930s it was felt by some that the whole bridge should be replaced by a more up-to-date one, but the wooden superstructure was found to be in very good shape. Electrical bulbs replaced oil lanterns in the 1940s, greatly reducing the risk of fire. In 1954 the deck was again replaced, this time by two-by-fours covered with asphalt-bonded crushed stone to make passage smooth for cars. In 1959, Line 86, which used the bridge on its way between Elmira and Guelph, was rerouted around the village. As the bridge was obviously unsuited to carry a high volume of modern traffic, the 86 bypass helped to preserve its integrity and, indeed, its survival.

228. In 1966, the bridge’s condition was found to be poor, so steel trusses from a bailey bridge were inserted to strengthen it. The trusses are concealed by those white panels in #226 above. In 1998 the bridge again needed substantial repair, but after public meetings it was decided to spend extra money so that it could still be used by light vehicles. The bridge was closed for 7 weeks and $268,000 was used to strengthen the structure, not including the donation of about $40,000 of volunteer labour. By this time, of course, the bridge was passionately adored by locals and the major tourist attraction of the area. It was, and still is, the most picturesque and beloved of all the 678 bridges in the Grand watershed.

229. The covered bridge naturally attracts lots of tourists. But the riverbanks it sits on are private property and ill-tempered signs make it clear that visitors are not welcome to wander there. Better park your car at the small P at the junction of River’s Edge Drive and Letson Drive, where there are various information boards about the bridge and West Montrose.

230. Why “Kissing Bridge”?

The locals suspected that courting couples walking or riding a buggy together would get intimate as soon as they entered the secluded interior of the bridge. Voyeuristic lads were reputed to conceal themselves in the interior roof beams so as to spy on lovers making out.

The Kissing Bridge Trailway runs 45 km from Guelph westward to Millbank. It occupies the eastern part of the former CP Rail Line from Guelph to Goderich, abandoned in 1990, and is maintained by volunteers. The Covered Bridge at West Montrose is the highlight of the Trailway, but it’s not actually on the Trailway, which crosses Covered Bridge Drive (Road 62) 1 km north of the bridge. As we have seen (#212 above), hikers on the Trailway have to make a long diversion here, the rail bridge having been demolished when the line was abandoned.

I‘m indebted to Del Gingrich’s Kissing Bridge (2009), a lively history of the bridge and the surrounding village of West Montrose, for much of the information here.

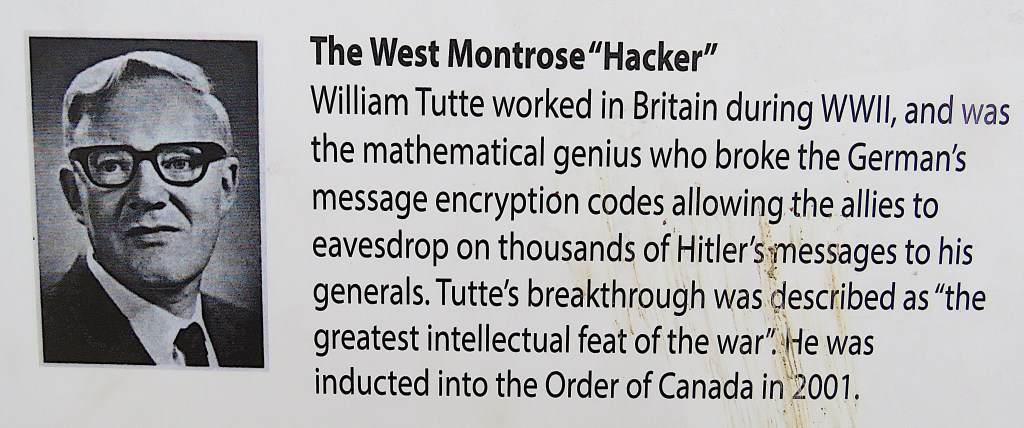

231. An information board at the P includes this brief portrait. Professor William Thomas (“Bill”) Tutte (1917-2002) was the most distinguished longtime resident of West Montrose. Born in Newmarket, England, the son of a gardener, he was a brilliant mathematician who was recruited from Cambridge University to the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, the now famous Allied code-breaking institute during World War II. Tutte made the key breakthrough with the Lorenz Cipher, used by the German High Command to send messages to officers of the Wehrmacht throughout occupied Europe. If I understand the reports correctly, he and his team were able to reverse engineer the Lorenz Cipher machine from its coded messages, without ever seeing what the actual device looked like. This was called “one of the greatest intellectual feats of World War II” when in 2001 Tutte was made an Officer of the Order of Canada. After the war Tutte moved to Canada, first to the University of Toronto and then in 1962 to the newly established University of Waterloo. Here as a professor of mathematics he founded the Department of Combinatorics and Optimization, which now has an international reputation. He and his wife Dorothea, an accomplished potter, bought a house in West Montrose overlooking the Grand, and the couple lived here until Dorothea died in 1994. Thanks to the conditions of the Official Secret Act, Tutte’s cryptological achievements, which directly contributed to the defeat of Nazi Germany, remained unknown to the public for years. Fortunately, and unlike his better-known Bletchley Park colleague Alan Turing, Tutte lived long enough to enjoy belated but much deserved acclaim. He and his wife are buried in West Montrose United Church Cemetery. For further information, see the Wikipedia article “Cryptanalysis of the Lorenz Cipher.” (If you can understand a tenth of it, you’re way ahead of me.)

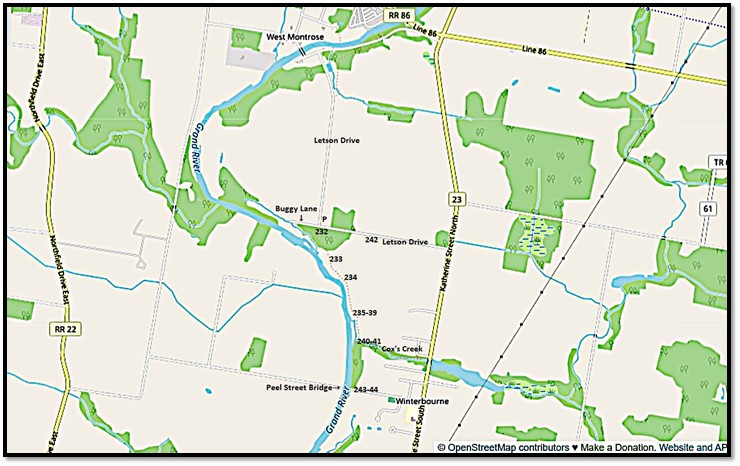

Map 19. West Montrose to Winterbourne

232. The next reach of the Grand is on private land. So I drive about 2 km south down Letson Drive to the amusingly named Buggy Lane, where near #1051 there’s a Grand Valley Trailhead.

The white blazes lead us through a wood …

233. … past a prosperous looking farm, where the even the steep riverbank is ploughed …

234. … and onto a river flat covered with peculiar hummocks.

235. The Grand itself is running entirely unfrozen …

236. … but those hummocks are piles of jagged ice fragments, evidently the aftermath of a recent thaw and break-up.

237. A male common merganser on the river. This big duck, a goosander to Europeans, is a diver for small fish in both fresh and salt water. The word “merganser” comes from two Latin words, mergere (to dive, to dip into water) and anser (goose). His long red bill has a serrated edge to help him retain fish. Awkward on land, he’s a superb flier, strong and arrow-like, but the river is wide enough here that he’s not spooked into taking off by my presence or that of my companion.

238. My companion? I was accompanied on most of this hike by this friendly black poodle. I’m guessing that it was attached to the farm on the crest of the riverbank, as it didn’t seem lost, merely in want of human company.

239. One of the swampy backwaters on this section of the Trail.

240. Soon my way south along the riverbank is blocked by the entry into the Grand of a vigorous creek from the east …

241. … it’s Cox’s Creek, which the trail follows as far as Short Street in the nearby village of Winterbourne. From that point, aside from a short detour into Snyder’s Flats, the GVT, keeping to the east side of the river, uses public roads, unaccountably avoiding the banks of the Grand for the next 14 km. To stay close to the Grand we’ll need to find a trail on the west side that actually follows the river’s course. Once we leave Woolwich Township and enter the City of Waterloo, there is such a trail, as we shall see in part 9.

242. Back to the car parked near Buggy Lane.

(Top) A short way east down Letson Drive, we come to Winterbourne Old Order Mennonite Meetinghouse, as unadorned a place of worship as you can imagine. It was built in 1965, expanded in 1986, and serves about 80 families.

(Bottom) Winterbourne Mennonite Cemetery adjoins the meetinghouse. The gravestones and their messages are as plain as the architecture of the building.

243. Not again! (see #206 ff above). This is what HistoricBridges.org had to say a decade ago about the Winterbourne Bridge on Peel Street, which it rated 8/10 for historic significance: “This impressive bridge is a very rare example of a multi-span truss bridge as well as a pin-connected camelback truss in Ontario. The bridge has excellent historic integrity with no major alterations, adding to its significance. Aside from some minor pack rust and section loss noted around some of the bottom chord connections, the bridge’s trusses remain in decent condition, however there is no paint to protect the steel of the truss from future deterioration. A substantial build-up of dirt was noted around the bearings of the bridge. A simple program of bridge washing where a truck is brought to the bridge to wash the dirt off the bridge with a hose is a low-cost maintenance effort that can go a long way to preventing section loss to the all-important steel of the bridge. Also, while more costly, a comprehensive rehabilitation of this bridge to address section loss, and to blast clean and paint the truss superstructure would prepare this bridge for another century of service.”

244. The view upstream from the east end of the sealed-off Winterbourne bridge on Peel Street. You now have to drive over 11 km to get from here where I’m standing to the opposite bank of the Grand north of those geese.

Instead of following HistoricBridges.org’s advice about how to prepare the bridge for “another century of service,” Woolwich Township closed it to all vehicular traffic in 2017. Its Council voted in February 2021 to rehabilitate the bridge for pedestrian use, though with no budget or timeline to do so. The following month they directed steel panels to be welded in place to seal off the bridge at a cost of $15,000. (How much would it have cost to have hosed it down periodically, or applied a lick of paint?) They claimed that their attempt to restrict the bridge to pedestrians and Mennonite buggies was being ignored. So the Peel Street bridge, the gateway to Winterbourne and the only Grand crossing between West Montrose and Conestogo, remains blocked and unmaintained. Demolition by neglect, as with the Middlebrook Bridge?

A Short Detour up the Conestogo River

The Conestogo River is the first of the main tributaries of the Grand you meet as you travel downstream. It’s an impressive waterway in itself, and it’s not surprising that Augustus Jones mistook its upper reaches for those of the Grand (see #117 above). It arises near Arthur and flows for over 50 km until it joins the Grand just below the village of Conestogo. As with Shand Dam and Bellwood Lake on the Grand, a flood control dam built 1955-58 on the Conestogo in Wellington County produced upstream a large reservoir, Conestogo Lake, now a popular recreational body of water. The river had been named the “Conestoga” by the Mennonite pioneers Benjamin and George Eby in 1806, as it reminded them of the creek of that name in their native Pennsylvania. That 60-mile-long creek in Lancaster County had given its name to the large, boat-shaped covered wagons in wide use in colonial America, and particularly in the vicinity of Philadelphia. Conestoga wagons were pulled by a team of four or more horses, and could be used as mobile homes by pioneers or as a means of transporting several tons of goods. The Ontario river and the village (pop. 1,300) named for it are both now spelled with a final “o” to distinguish them from their US namesake.

Map 20. Conestogo, St. Jacobs, and the confluence of the Conestogo and Grand Rivers.

P on the side of Sawmill Road in Conestogo village and walk down the steep hill to the bridge on Glasgow Street. There’s a large free P in St. Jacobs village. Parking is also free at the Farmers’ Market though spaces are difficult to find. Be prepared to be patient and walk a distance. The rivers’ point of confluence is at 248 above. There’s an informal P on the river side of Sawmill Road that gives you access to the east bank of the Grand a little way downstream from the fork.

245. (Top) The bridge over the Conestogo on Glasgow Street South in the village of Conestogo. Built in 1886 by the Hamilton Bridge and Tool Company, it’s one of the oldest metal bridges in Canada, and accordingly accrues a grade of 9/10 in Historic.Bridges.org’s heritage rating system. A well-meaning study by Waterloo Region (see Fontaine) failed to appreciate how old this bridge is, dating it incorrectly to 1928 and thus by implication less worthy of preservation. Well, the bridge, which connects Conestoga to the Waterloo townline, was still open when I visited. But I counted 14 warning signs at the bridge approach, surely a world record, and suggesting to me that the local authority is looking for any excuse to weld it shut and let it rust to pieces!

(Bottom) Viewed from the bridge, the Conestogo River flows east to its junction with the Grand about 1.5 km away. Here in the Conestogo’s lowest reach there is little to distinguish the tributary from the main waterway.

246. About 5 km west of Conestogo is the touristy village of St. Jacobs.

(Top) King Street North, the main drag.

(Middle) An Old Order Mennonite lady sells handicrafts at her sidewalk stall.

(Bottom) The Village Biergarten attracts crowds of beer lovers on this fine day.

247. The St. Jacobs Farmers’ Market, the biggest visitor attraction in the region, is not actually in the village of St. Jacobs, but 3 km south on Weber Street on the Woolwich side of the boundary with the City of Waterloo. It’s reputedly Canada’s largest farmer’s market, attracts over a million visitors a year, and is open Thursdays and Sundays all year and some Tuesdays during summer.

(Top) If you come on a fine day, be prepared to hustle for a parking place and for serious crowds.

(Middle) A juggler is one of several entertainers in the outside market soliciting cash contributions.

(Bottom) The indoor market is pretty crowded too. The line-up at this apple fritter stand stretches outside and around the block.

248. We’re back in Conestogo, opposite the point (top) where the Conestogo River joins the Grand. This was where in 1807 Captain Thomas Smith (1767-1850) a Loyalist born in Vermont and his wife Mary, the earliest settlers in the area, built a two-storey log house (left), now demolished. Their daughter Priscilla, one of 15 Smith children, was the first non-native child born in Woolwich Township. What is now Sawmill Road was then a native trail, and the hospitable Smiths would frequently entertain travellers on it. Fellow Vermonter Roswell Matthews (see #168 above) arrived here with his exhausted wife Hannah and their eight children in 1817 on his way to what is now Elora. The Smiths took in Hannah and her six younger children for the whole of their first winter on the Grand while Roswell and his two oldest sons went ahead to prepare their settlement. In 1819 some of the families on their way to settle the Pilkington “estate” (see #198 above) stopped here too. A motherless baby girl born at sea was adopted by the Smiths permanently; she eventually married one of their sons. And then in 1837, in a turn of events sadly not infrequent in pioneer days on the Grand, the Smiths were evicted from the house in which they’d lived for thirty years due to their lack of title to the land – in the eyes of the law they were squatters. Let no good deed go unpunished!