The Grand River, swollen by the waters of its major tributary the Conestogo, now enters for the first time an urban area, the Regional Municipality of Waterloo. This consists of the conjoined twin cities of Kitchener (pop. 260,000) and Waterloo (130,000), and, barely separated from them to the south, Cambridge (140,000). Together these three cities (K-W-C) and their periphery form a metropolitan area of pop. 575,000, the tenth-largest in Canada and one of the fastest growing. K-W-C is a polycentric sprawl, and it’s about a 40 km drive between its northern and southern edges. A canoeist on the Grand, which takes a leisurely serpentine path through K-W-C, will travel almost twice that distance between those two edges.

The Left Bank: Waterloo and Kitchener North

Numbers on the maps correspond to the numbered entries below them.

Map 21. A blue dotted line marks the approximately 4.5 km one-way hike along the left bank of the Grand River from the P in RIM Park to the northern end of the Walter Bean Grand River Trail at the Waterloo/Woolwich boundary (Country Squire Road).

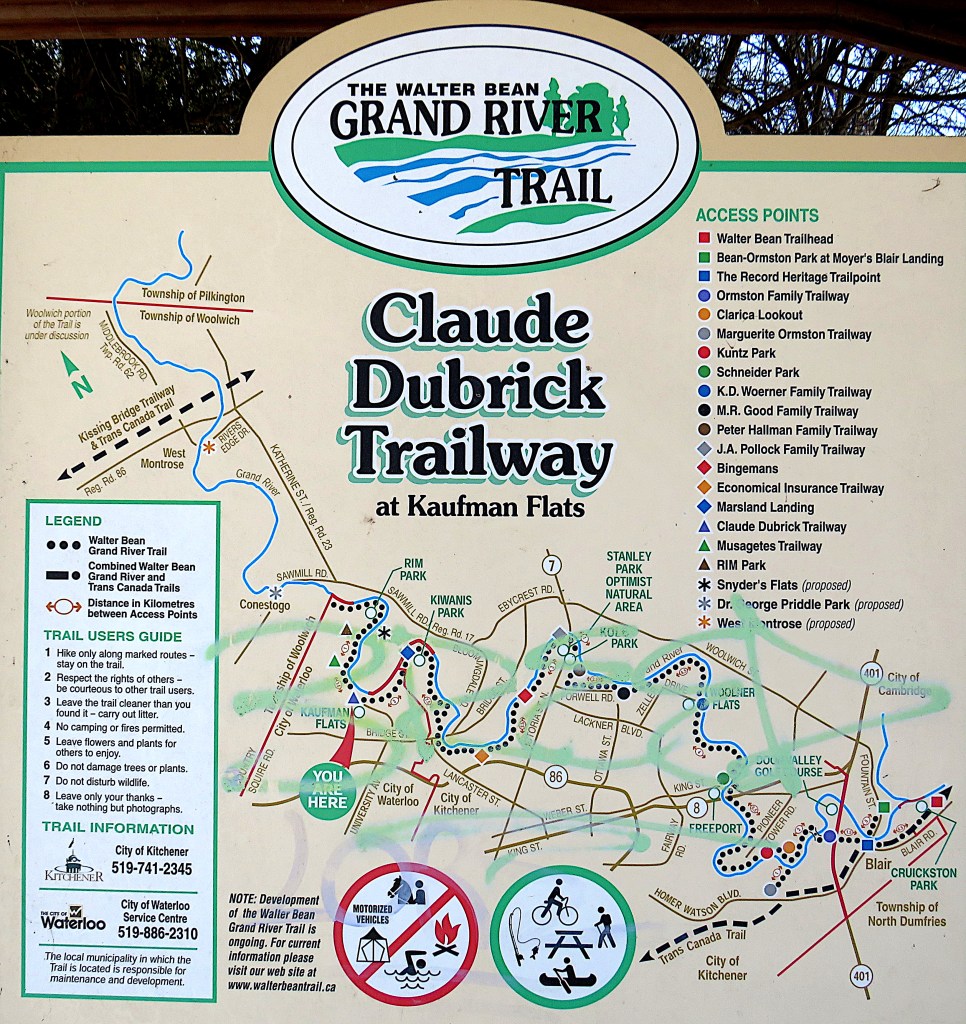

249. For those of us following the Grand as closely as possible, there’s good news: on the left bank the Walter Bean Grand River Trail (WBGRT) begins. It’s a 76 km multi-use trail that traces our river’s sinuous course through the three cities.

Walter Alexander Bean (1908-98), born in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, rose to the rank of Brigadier-General in WWII. He was posted to the staff of Admiral Nimitz at Pearl Harbor and was one of the few Canadians to take part in the Battle of Peleliu. After the war he served as an executive in various K-W financial organizations and on many local boards. Bean had a vision: to enable his fellow citizens to “experience the beauty of bald eagles, cormorants and limestone cliffs that were just minutes from the busy downtown streets where he grew up peddling newspapers.” Sadly, he didn’t live to walk the trail that bears his name and preserves his legacy. The Kitchener Director of Parks adds: “For me what stands out particularly about this trail is the focus on the river. The trail connects communities along the river and the river is the central focus for the trail. It serves a recreational need most directly – it is built primarily to connect community with the river and each other” (Pace).

The WBGRT is owned jointly by K-W-C. As a work in progress the Trail can sometimes be a little frustrating for hikers. Some sections are incomplete, others are closed as they are under repair from flooding. Moreover, there’s nowhere to park at its northern end! You have to leave your car at the RIM Park P and hike the first few km of the Trail south to north, then return the same way. (See #259 below for why a loop hike isn’t recommended.) Yet regardless of its flaws, the WBGRT is an excellent resource for hikers and lovers of the Grand River at every time of year.

250. The Elam Martin Farmstead stands by the P in RIM Park. Above is the 1860 barn and associated buildings in this sixth-generation farmstead founded in 1820 by Mennonite immigrants from rural Pennsylvania. Although the City of Waterloo owns the property, members of the Martin family still live on it. The 14 structures on the site are listed under the Ontario Heritage Act.

What is now Waterloo was in Block 2 of the Haldimand Tract, granted to the Six Nations in 1784 and purchased from them in 1798 by Richard Beasley and two associates, settlers at the head of Lake Ontario. So how did American Mennonites come to settle the Waterloo area? And why did the Six Nations receive only a tiny fraction of the proceeds of the sale of their land? Joseph Brant, who had been granted power of attorney over Six Nations lands in 1796, has sometimes been seen as the culprit in the latter case. Some historians have viewed him as too naïve to negotiate effective business transactions; others, in total contrast, as too deviously concerned with enriching himself. But E. Reginald Good offers in my view the clearest exposition of what happened, one that hardly involves Brant at all.

In what was a familiar story, Beasley lacked sufficient funds to pay down the mortgage. So he sold on a 6,000 acre portion of his land to two Mennonite immigrants from Franklin County, Pennsylvania. This pair, George Bechtel and John Bean, were unaware that, as Beasley’s mortgage was outstanding, they had no legal claim to the land title.

By this time (1800) Joseph Brant, having been been falsely accused of self-interest by William Claus of the Indian Department, had been essentially stripped of his power to deal with Six Nations land sales. There had been a sea-change in the colonial government’s attitude toward Brant’s people. At the time of the Haldimand Proclamation, the Six Nations had been regarded by the British as essential military support against a possible American invasion. But this threat receded after the Jay Treaty of 1794 defused tensions between the British Empire and the USA. Now the colonial administration resolved to take total control over sales of the Haldimand Tract and use the proceeds for the benefit of white settlers.

In 1803, Beasley, struggling financially, offered to sell 60,000 acres of Block 2 to the Mennonites for the huge sum of £10,000. The Mennonites, keen to acquire excellent agricultural land, went back to Pennsylvania and organized the German Company, a syndicate of 26 stockholders. The first instalment of the purchase fee in US silver dollars arrived with Mennonite agents Samuel Bricker and Daniel Erb in a Conestoga wagon from Pennsylvania surrounded by armed guards. Though they were Americans, the Mennonites were considered ideal settlers by the British. Not only were they scrupulously honest and paid their debts, but also they favoured the Crown and were pacifists, therefore unlikely to indulge in republican agitation. Of the £10,000, a mere £513 interest payment went to Six Nations chiefs, while William Claus, the villain of the piece, illegally siphoned off almost £2,000 in personal expenses. Good concludes, “The Six Nations currently are seeking an accounting from the Crown of their land sales proceeds. … To date Canada and Ontario have failed to provide this accounting” (99).

Of the Mennonite German Company stockholders, it was Abraham Eby who arrived in this area in 1806 and in 1816 founded the village that would eventually become the City of Waterloo. It was of course named for the great British/Prussian victory over Napoleon the year before.

While the Grand River was central to the development of Waterloo County, it played a lesser part in the history of what is now the City of Waterloo. Indeed, only a small section of the left bank of the Grand is actually in that city.

251. I wanted to document the Grand in midwinter. There are a few inches of snow on the ground in early January and there’s an unpleasant windchill making it feel about -10C, but the Grand is flowing freely.

252. The Trail crosses a small creek just before it empties into the Grand. It too is unfrozen.

253. In a prominent position on the other side of the river looms a McMansion. A what?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “McMansion” thus: “A modern house built on a large and imposing scale, but regarded as ostentatious and lacking architectural integrity.” To this I’d add that the word obviously alludes to the ubiquitous McDonald’s fast food chain with its supersized burgers. “McMansion,” then, suggests that the builders – I hesitate to call them architects – use cheap materials to achieve an effect in which size trumps aesthetic considerations. It implies that the owners of these houses, like those who stuff themselves with fast food, simply lack a taste for anything finer.

So “McMansion” is definitely a pejorative term. Is it justified? I fear it is. Check out Kate Wagner’s blog McMansion Hell if you want a thorough and very witty deconstruction of McMansiondom.

There’s no doubt that the house above is large and ostentatious. The owners evidently want to look out over their domain, as they have removed all the vegetation on their level. Likewise they want their property to be seen and admired, not only by walkers along this trail but also (in season) by golfers on the upscale Grey Silo course on this side of the river.

As for “lacking architectural integrity”: look how the voids (window areas) overwhelm rather than balance the masses (blank walls). Look at the unharmonious structure with its awkwardly positioned chimney, multi-garage excrescence at right, and pointless “bonus nub” on the roofline. And look at the turrets at right and left and the central pseudo-turret. As Kate Wagner puts it: “Previously in architecture, turrets were found only on houses whose architectural styles were influenced by the Medieval … Sometime in the late 90s, somebody began equating turrets with the illusion of wealth, and thus the Turret Age was upon us.”

By some, Wagner’s scoffing will be dismissed as mere snobbery. So I’ll venture that there’s a more serious consequence to the placement of McMansions like this. By monopolizing land on the edge of high ground, McMansions have become a major threat to the existence of public trails, especially those enabling the enjoyment of viewpoints, e.g., over the Grand River. It’s already hard enough to find public access to the bank of the Grand on the Woolwich side around here. And there’s no guarantee that more McMansions won’t threaten the continuity of the WBGRT on the left bank as well. Go to #256 below to see what I mean.

To offer another local example: wherever the top edge of the 900-km-long Niagara Escarpment is not owned by the Bruce Trail Conservancy or protected by a Conservation Authority, McMansions proliferate, forcing hikers on the Bruce Trail, Ontario’s oldest long-distance footpath, onto the shoulders of public roads.

254. The WBGRT signage indicates that the Trail isn’t maintained in winter. However, the foot traffic along it is usually enough to ensure that it’s walkable, even after a snowfall.

255. Soon we come to this information board. RIM Park is indeed on the rim of the City of Waterloo, but it gets its name from the acronym of its chief donors, the employees of Research in Motion. That was the software company founded in 1984, based in Waterloo, and later renamed BlackBerry. It made early smartphones that were very popular until gradually superseded by iPhones and Androids from 2011 onwards. These days BlackBerry confines itself to developing software security systems.

256. This McMansion occupies the bank on our side of the river, throwing the Trail briefly onto Grand River Drive, a public road boasting a cornucopia of McMansions. The back garden protected by this see-through fence along the Trail hardly offers monastic seclusion … but as we have seen, in the McMansion universe, ostentation trumps privacy.

257. Once past #256, we can get off the road to follow the Trail along the top of the riverbank …

258. … and find ourselves here, at the northern end of the WBGRT. No parking anywhere around here!

259. We’re on Country Squire Road looking southwest. This is the townline separating Woolwich Township on the right from Waterloo Region (here the City of Waterloo) on the left. You could follow that guy and loop back to your car in the RIM Park P via Grey Silo Road and Woolwich Street, a short cut of about 2.4 km. But you’ll notice that there is no sidewalk or shoulder, snow has reduced the width of the road, and that’s a blind hill coming up. Probably safer to turn round and retrace your steps.

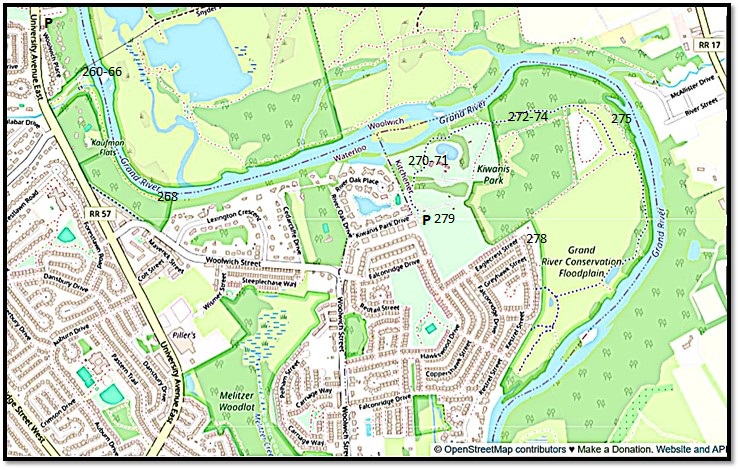

Map 22. Kaufman Flats and Kiwanis Park. As the access road to the Kaufman Flats P is closed in winter, you have to park on a side road off University Avenue East and walk in. The trail here does not yet connect to either RIM Park or Kiwanis Park. At the latter, there’s a good-sized free all-weather P at the end of Kiwanis Park Drive.

260. I plod down to the Kaufman Flats trailhead, where there’s a map showing the current WBGRT. The continuity suggested by the black dots is a little misleading. To get here from RIM Park you have to walk along University Avenue, and to get to Kiwanis Park you have to walk along Woolwich Street. The Claude Dubrick Trailway, as it’s called, is only about 500 metres long, but it does provide good access to the Grand.

261. It’s now the end of January. The weather has been chilly for most of the month and the surface of the Grand is mostly iced over. Upstream a few ducks huddle in a patch of open water where the river bends. The left bank in that direction is private property.

262. The Dubrick Trailway is not well trodden, but that’s hardly surprising as it’s a dead end. It’ll be a challenge to link this trail up with the WBGVT in RIM and Kiwanis Parks, given the increasing encroachment of private properties on the riverbank.

Someone has constructed a sort of wintry version of inuksuit on that bench. There on the other side of the river …

263. … sits an osprey nest on a tall pole. It stands in Snyder’s Flats (see #280 below). At this point the Grand sweeps in an almost symmetrical oxbow, and I’m near the centre of its outer edge.

264. How firm is the ice surface? If these footprints are any guide, not very. Someone started to cross the river here, only to turn back half way.

265. See that dark slash on the surface of the Grand? Look closely and you can see that the river is fast flowing beneath a thin skin of ice.

266. There’s an elegant little bridge over a small creek at the start of this trail. Those steps on the other side, however, lead up to a private property.

267. The high wooded bank under which I’m walking conceals several new buildings. This McMansion is the only one so far to eschew modesty and descend close to the trail, defending itself from flooding by a flight of massive stone steps serving as a retaining wall.

268. The Dubrick Trailway comes to an end just as the river curves east to complete its oxbow. Look how blue the shadows are on this clear, cold sunny day! One of the first to depict coloured shadows like these was Claude Monet, the pioneer Impressionist, in his snowscapes such as “The Magpie” (1869). Of course, the Paris Salon rejected such paintings for not being true to life!

269. On to Kiwanis Park. You can’t drive in at this time of year, but there’s a P to the right of the entrance.

270. A close-up of the map here shows the borders between Woolwich Township, the City of Waterloo, and the City of Kitchener as red lines. Only RIM Park and Kaufman Flats are in Waterloo. We have now crossed the border into Kitchener. Woolwich occupies the right bank of the river for a long while yet.

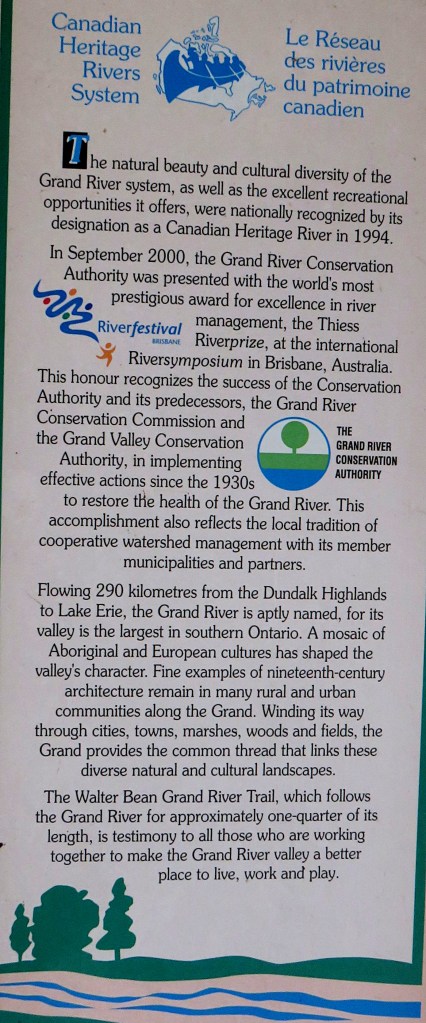

271. I suppose I should have already mentioned that the Grand and its major tributaries constitute a designated Canadian Heritage River. There are 42 of these CHRs in Canada, 12 in Ontario. The Grand was so laurelled in 1994, primarily for its cultural history and recreational opportunities. That history includes First Nations settlements both ancient and modern, as well as later Loyalist, Scots, Irish, Mennonite, and German arrivals. However, aside from granting the river a certain tourist cachet, it’s unclear what else such heritage status involves … or what it would take to lose it. Would allowing the Grand’s high banks to be lined with McMansions put its heritage status in jeopardy?

The Grand River Conservation Authority has to submit a satisfactory report to the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) Board once a decade if CHR status is to be maintained. The 2014 report is here. The 2024 report is yet to be published.

272. A few scenes from wintry Kiwanis Park. The Trail here is popular and well trodden.

273. Yet another McMansion under construction on the right bank.

274. Regimented evergreens.

275. Frazil ice covers the surface of a narrow bend in the Grand. It forms when turbulent water – waves or rapids – freezes quickly.

276. Definitely not a McMansion! For a start, it’s not beige or grey … though come to think of it, if McMansions were all clad in bright primary colours, would the world be a better place?

276. A delicate caterpillar formed of ice crystals sits on a fallen bough by the riverside.

277. I loop back to the P via the Bridgeport North survey. You can have one of these regimented houses in any colour you like, as long as it’s beige. Or grey.

279. There’s a hockey game taking place on an improvised rink by the P in Kiwanis Park. A quintessentially Canadian Winter Scene, like the sign says.

The Right Bank: Snyder’s Flats

Map 23. Snyder’s Flats Conservation Area occupies the inner, Woolwich side of the oxbow. It’s definitely worth visiting for a hike at any time of the year, as it has an open, rural feel quite unlike the rapidly urbanizing left bank of the river. To get there, take Sawmill Road to the village of Bloomingdale, then go west along rough-surfaced no-exit Snyder’s Flats Road. There’s a small free P at the end of this road. There are many trails in this Conservation Area, the main ones indicated by small red dots on the map. Only the trails on the northeast and southern sides of the Flats allow good views of the Grand itself. Note: as there are no bridges over the Grand in the vicinity, it’s a 10 km drive from Kiwanis Park to Snyder’s Flats, even though it’s barely 1 km as the crow flies.

280. “A natural area”? It would be truer to say that from 1979-87 Snyder’s Flats was a huge open gravel pit that is still being naturalized. There’s native grassland, two types of forest, three ponds, and, if you’re lucky, ospreys, beavers, deer, turtles, minks, coyotes, and many other kinds of wildlife. However, as just about every dog walker fails to comply with the instruction on the sign, the wildlife is elusive when dogs are running freely, which is most of the time.

281. Just by the P, there’s a section of former gravel pit that hasn’t yet been naturalized, so you can see what the area used to look like. The naturalizers have done a great job with the rest of the Flats, no doubt about it.

282. The Grand looking upstream in March. There are well-placed benches with peaceful views over the river and the ponds …

283. … like this one.

284. That relatively modest housing development is on the Waterloo side of the Grand. However, this side will soon see a number of “dream homes, amid nature’s splendor” (i.e., McMansions) built on a lot on the south side of Snyder’s Flats Road close to Bloomingdale. I’ve put an X on Map 23 where this already sold-out development is to occur. If you’re curious about how utilities might be provided to giant homes in this rural area, you should know that electricity and natural gas hookups are available locally, water comes from individual wells, and sewage goes into septic tanks whose treated contents hopefully don’t make their way into local waterways.

285. That’s definitely a sign of beaver-related activity …

286. … and this is where the perps live. No sign of them today.

287. Fast forward to October. Cormorants and gulls share that little island on one of the ponds. As these ponds occupy a floodplain, the Grand periodically overflows into them, restocking them with fish.

288. Toadflax (a.k.a. butter and eggs) on the native grassland section of Snyder’s Flats. It’s slightly ironic to find it here, as it’s considered an invasive noxious weed. But I’m not complaining, as it’s rather beautiful.

289. A marshy area on the way to the southern sector of Snyder’s Flats. This lowland forest of native trees, planted as recently as 2009, includes silver maple, white cedar, bur oak, basswood, black walnut, and varieties of dogwood and willow.