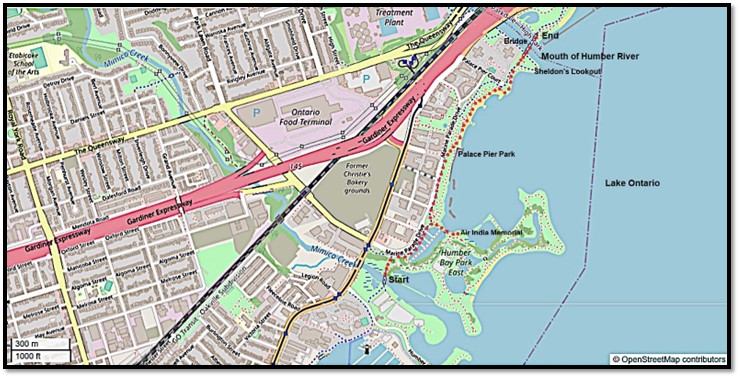

32. Today’s hike, marked as usual with red dots on the map above, is about 1.5 km, or 2 km if you make a side trip to the Air India Memorial. It goes from the north side of the Mimico Creek Pedestrian Bridge to the northeast side of the Humber Bay Arch Bridge. As there is a network of paths along the lakeshore and around Humber Bay Park East, it’s easy to extend the hike by a couple of km and do a loop. If you arrive by streetcar or bus, your best stop is Lake Shore Boulevard West at Park Lawn Road, from where it’s a very short walk to the Waterfront Trail. If you come by car, you’ll park at the large P at Humber Bay Park West (see Part 1).

33. Even more than the previous hike, this one has two completely different facets. On the one hand, the shore of Lake Ontario is lined by giant condominium towers with pretentious names, and several more are under construction at any given time. Above is the scene that greets you as you cross the Mimico Creek Bridge heading east. At left is the Eau du Soleil Sky Tower (750 units, 66 storeys, 228 m, 2019), currently the 11th tallest tower in Toronto and the 14th tallest in Canada. It’s Toronto’s, and Canada’s, tallest skyscraper outside a central business district, at least for the moment. It’s connected at podium level to the Eau du Soleil Water Tower (330 units, 49 storeys, 179 m, 2019), merely the 38th tallest in Toronto. Between the two, with its slightly wavy profile, is Jade Waterfront Condos, which at 138 m doesn’t even make it to the list of the more than 80 skyscrapers in Toronto over 150 m in height …

34. … while on the other hand, the narrow strip of land between the towers and the lake has been laid out imaginatively, with a network of paths through butterfly gardens, wildflower meadows, and ponds, all open to the public, that make this high density area surprisingly pleasant to stroll through. In case you’re interested, there’s an elaborate 148 pp Master Plan of this area by the City of Toronto published in December 2018. The way the plan was assembled and implemented is very impressive.

35. At the foot of the Eau de Soleil Towers is a large pond that serves to manage stormwater. A long boardwalk spans it, a quieter alternative to the paved onshore trail.

Conservation Authority

The pond is a Dunkers flow balancing system, named after its Swedish inventor. It’s a relatively cheap and ecologically sound way of dealing with overflow from storm sewers. As you can see from the aerial view, taken before the construction of most of the towers (left), the pond is divided into 5 cells. They are separated by PVC curtains suspended from floating pontoons. “During a rain event, stormwater or combined sewer overflow enters the first cell, displacing the cleaner water into the second cell. Similarly, the remaining cells are filled in sequence before the polluted water can enter the lake. After the rain event, polluted water stored in the facility is pumped to a wastewater treatment plant while clean water from the lake or ocean refills the cells.”

36. The boardwalk across the pond is a good place to get upclose to waterfowl.

37. A pair of tree swallows rests briefly on the wire strung through the boardwalk balustrade. The male boasts the iridescent blue plumage.

38. Just after the boardwalk ends, turn right and cross this small bridge over the outflow from the stormwater pond into the Lake. That’s a fine pair of swans under the bridge.

39. They are trumpeter swans, the largest native North American bird. They average 1.5 m in length and have a wingspan of up to 3 m. Adults weigh up to 30 lbs, making them one of the world’s heaviest flying birds. Once seriously endangered, their numbers have recovered and they can now be found quite often on the lakeshore of the Golden Horseshoe, even overwintering here. Their black bills and greater size distinguish them from orange-billed mute swans, an introduced species.

40. Red-necked grebes also like the stormwater ponds, as they are a good shallow place to build their floating nests. In fact this one is busy adding twigs to the nest on which his mate is sitting in brood.

41. A couple of hundred metres after the little bridge you’ll arrive here …

42. … at the Air India Flight 182 Memorial to the victims of Canada’s worst-ever terrorist atrocity. On 23 June 1985, a bomb exploded in the cargo hold of an Air India Boeing 747 on a flight from Toronto via Montreal and London en route to New Delhi and Mumbai. The plane disintegrated in midair and fell into the Atlantic off the west coast of Ireland, killing all 329 people aboard. Lax security had allowed a timebomb to be placed in a suitcase not belonging to anyone on the plane. It had probably been put there by a militant Sikh separatist organization based in Vancouver with animus against the government of India. The suitcase was subsequently transferred to the Air India flight. Thanks partly to subsequent bungling by Canadian security services, only the bomb maker, and not those who had conspired to place the bomb, was ever brought to justice.

The black wall contains the names of the dead, 268 of them Canadian citizens, mainly from the Toronto and Montreal areas. The wall also commemorates the two Japanese baggage handlers killed on the same day when another timebomb, in baggage due to be transferred from a Canadian Pacific plane to an Air India one, exploded prematurely at Narita airport in Tokyo.

These outrages had been planned and executed in Canada and by far the majority of its victims were Canadian citizens. Yet nine out of ten Canadians surveyed in June 2023 had little or no knowledge of this, the world’s most deadly terrorist action against an airliner before 9/11. To understand why, and for more information, read this report by Canada Public Safety.

43. The Memorial’s sundial is on a base constructed from stone from each Canadian province and territory as well as from four other countries most directly affected by the bombing. The gnomon – the part of the sundial that casts a shadow – is oriented toward the site of the bombing, near Ireland. Around the edge reads: “TIME FLIES / SUNS RISE AND SHADOWS FALL / LET IT PASS BY / LOVE REIGNS FOREVER OVER ALL”. The Flight 182 Memorial was dedicated in 2007, on the 22th anniversary of the bombing.

44. The view of the lakeshore from Humber Bay Park East suggests that the parkland dividing the condos from the Lake is pretty thin. That cylindrical tower is Waterscapes at 80 Marine Parade Drive …

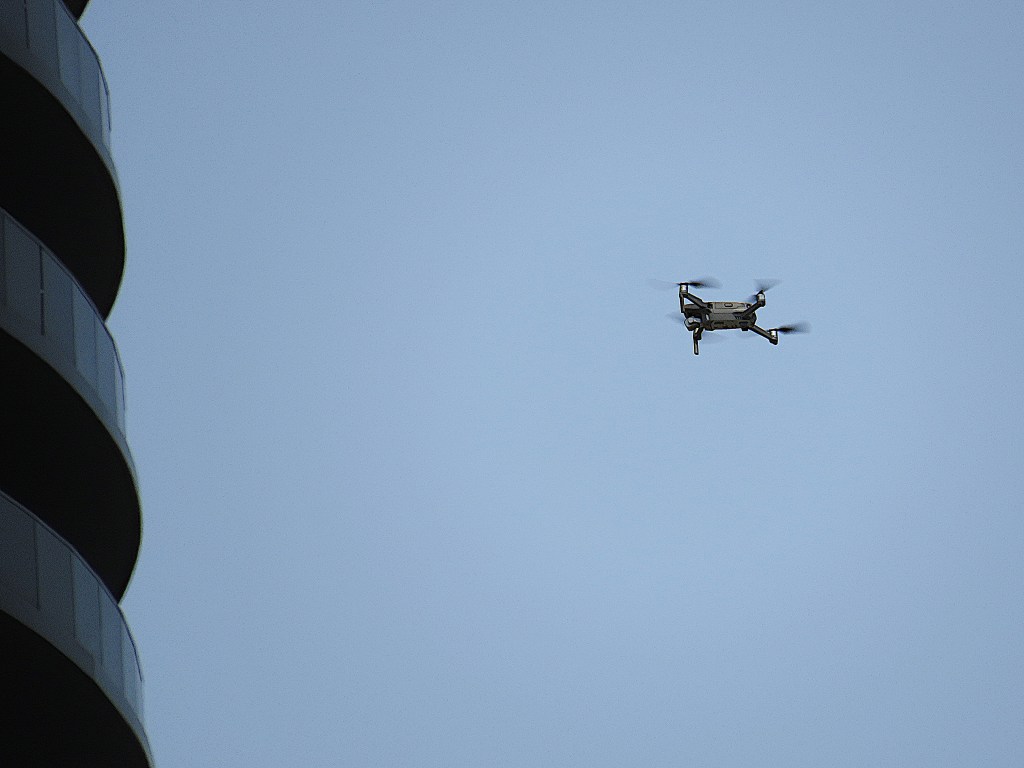

45. … and my eye is caught by what seems at first a large bird seeking to alight on one of its balconies …

46. … but actually it’s a drone. Is it taking a video of this highrise cluster, or is it voyeuristically peeking into the interior of one of the apartments? Here are some of regulations governing drone-flying in Canada. Maintain line-of-sight at all times. Don’t fly higher than 122 metres above the ground. Don’t fly closer than 30 metres from people and animals for basic operations. Keep a safe distance from buildings and vehicles. Don’t fly closer than 5.6 km from an airport, 1.9 km from a heliport. To these, I’ll add: Don’t expect privacy these days if you live in an eye-catching glass-walled cylinder thirty stories high.

47. At this point the area between towers and lakeshore is broader than it might appear. These are the paved walking and cycling trails that run parallel to Marine Parade Drive in Humber Bayshores Park. There are quieter, more rustic paths closer to the waterfront …

48. … but the view away from the lakeshore is dense and urban. There are more than fifty high- and mid-rise condos on the Humber Bay lakeshore, and every apartment has its own balcony. These balconies are supposed to provide “stunning” views while helping those living in confined quarters in these dense developments avoid claustrophobia. But the winds at elevated altitudes, vertiginous drops, and external noise can make it too uncomfortable for condo dwellers to sit out on their balconies, even in summer. So balconies are frequently used just for storage of large items like bikes and barbecues. Such heavy metal objects may accidentally collide with balcony glass. There have been many “falling glass incidents” in Toronto when parts of balconies in older towers have abruptly descended on the street below. Developers are now encouraged to use more expensive laminated glass (of the kind used for car windshields) on balconies, at it’s supposed to retain its structure better if damaged.

49. We’re getting a bit closer to downtown. A powerboat scatters a flight of cormorants. That horizontal structure at right of the foot of the CN Tower is BMO Field, the home of Toronto FC of Major League Soccer and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League. It was built in 2007 and holds about 31,000 fans.

50. Dying for a snack? No design is too garish for the trucks of Toronto street food vendors.

51. The Butterfly Garden at lilac time doesn’t seem to be hosting many butterflies. This elaborate birdhouse at its centre forms an interesting contrast to the rather brutal backdrop.

52. A real sparrow sits on one of the welded steel ravens perched on metal poles in the Home Garden. The raven, whose hollow interior can be used as a nesting place, is part of an installation called “Guardians” by Amy Switzer (Canadian, b. 1971).

53. Many birds in this area have adapted to having humans in close proximity and don’t startle easily. The iridescent feathers of this common grackle shine in the spring sunlight. The larger size and brighter colours of this bird indicate it’s a male. Grackles are omnivorous and can frequently be found foraging in gangs around the foot of bird feeders.

54. The yellow flowers of bitter wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris) are in evidence everywhere in the Wildflower Meadow in May, here framed by forget-me-nots.

55. As most of Humber Bay is open to the main Lake, your peaceful stroll will be periodically shattered by the racket from personal watercraft. An RXT, the most powerful model of the Sea-Doo line-up, starts at $20,000, and yes, it is designed to carry up to three people.

56. A reverse-angle view of Palace Pier in the foreground and the central mass of condo towers at back, looking west from Sheldon Lookout.

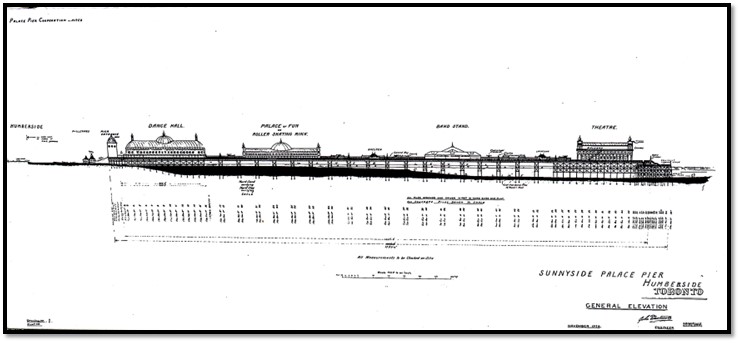

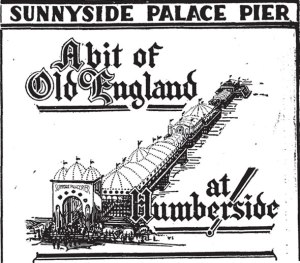

57. In the 1920s there was a grand plan (above) to build an amusement pier here into Lake Ontario that would be as much an attraction as the piers at English seaside resorts, in particular the Brighton Palace Pier (built 1899, and a major attraction even today). Construction of Sunnyside Palace Pier began in 1931. It was planned to be a third of a mile long and contain a Dance Hall, Palace of Fun, Band Stand, and Theatre, with a steamship dock at the end. But thanks to the Depression only the Dance Hall (at the left of the plan above) was completed in 1941. As a ballroom hosting big bands, it was very popular during the 1940s and 1950s, hosting performances by such names as Duke Ellington and the Dorsey Brothers. It and the stub of a pier it was built on burned down in 1963, probably as a result of arson. Two condos near the site, the Palace Pier North and South Towers, as well as historical markers affixed to one of the original pier footings, keep the memory alive.

58. The Sheldon Lookout is the last promontory before the mouth of the Humber River. For no obvious reason, it contains an assemblage of large rocks, standing and recumbent. One rock serves as a sundial, indicating the direction of sunlight at the summer and winter solstices. So perhaps this is Toronto’s answer to the megalithic sites of Europe.

59. The Humber Bay Arch Bridge, intended for pedestrians and cyclists, is 139 metres in length, spanning the 100 metre width of the Humber River only a few metres from its mouth. This striking bridge was designed by Toronto architects Montgomery Sisam and constructed in 1994. Here it’s viewed from the eastern bank of the Humber River looking towards Lake Ontario.

60. The view upstream from the Bridge is not very attractive, as it is largely blocked by low road bridges carrying Lake Shore Boulevard West, the Gardiner Expressway, and the Queensway over the River. This is a pity, as on the bank at left is the start of a historic and appealing walk north up the Humber Valley, that is, along the opening stretch of the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail (see #65 below). But to get to it you have to negotiate the dank gloom under all those ugly bridges.

61. Humber Bay is a basket-handle through-arch bridge, in which the two ribs that support the deck lean together, so there is a shorter distance between them at the top of the arch than at the bottom.

62. Can you make out the stylized Thunderbird in the metalwork that divides the two arches? The Thunderbird is a supernatural being in the belief systems of many North American First Nations, and has frequently been depicted in aboriginal artwork (see example left). This motif in the Bridge is a deliberate reference to the importance of this spot historically to First Nations and their part in the evolution of the city of Toronto (see below). The snake motif (right) on one of the bridge’s abutments is intended as a reference to the area’s aboriginal history and to the wildlife that used to frequent the area.

63. This is the underside of the bridge. I’m following the trail of some barn swallows that disappeared under here.

64. And here they are, occupying these cup-shaped nests built of mud pellets attached to the concrete under-surface of the bridge. These very common swallows differ from tree swallows (#37 above) by having a red face and a blue breast band.

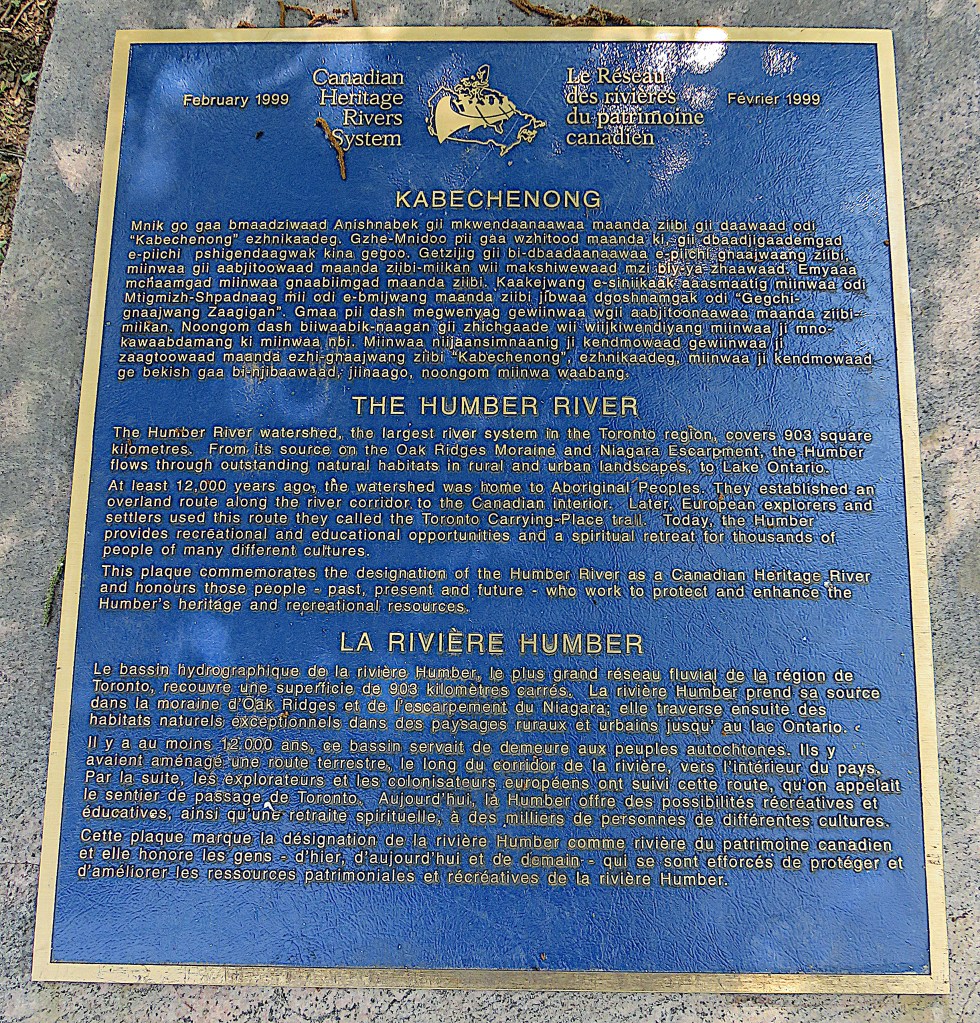

65. The origin of Toronto’s name. This trilingual sign in Ojibwe, English, and French stands near the mouth of the Humber River. The city whose centre is east of here owes its name to this river, though very indirectly. How it came to do so is rather complicated, so I’ll try to summarize the story briefly. Forgive me if I’ve omitted some important details.

The Humber River was known as Kabechenong in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), the language of the Mississauga, the dominant Anishinaabe First Nation in this area when European settlement began. In the late seventeenth century the Mississauga built a seasonal village on the west bank of the Humber which lasted for more than a century. It was well positioned at the southern terminus of an ancient, major First Nations portage route connecting Lake Ontario, the twin Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, and Lake Huron. In other words, it was at one end of a short cut between two of the Great Lakes.

Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the narrows between Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, well over 100 km north of present-day Toronto, there were some fishing weirs. The old photo (right) will give you an idea of what they may have looked like. In Kanyen’kéha, the Iroquoian language of the Mohawks, the word for these places where fish could be trapped and easily caught is tkaronto, literally, “the place where trees [i.e., wooden stakes] are standing in the water.” As there were no Mohawks settled in the vicinity of these weirs, possibly a Mohawk guide gave this name to European explorers. In the 1680s among French voyageurs – fur traders who travelled by canoe – this became Taronto, and Lake Simcoe was called Lac de Taronto on early French maps. Soon thereafter the Humber River became La Rivière de Taronto. The site of the Mnjikaning (the Ojibwe name is now used) Fish Weirs near Orillia is now a National Historic Site of Canada.

The variant spelling Toronto for the lake and river was preferred by early Anglophone map-makers, who referred to the whole portage route as the “Toronto Carrying-Place Trail.” The French had built a trading post, Fort Toronto, near the mouth of the Humber in 1750. After the area became part of British North America, the current city was founded about 8 km east of here in 1793 as “York” by John Graves Simcoe, the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada (now Ontario). Simcoe’s policy was to anglicize placenames. It was he who renamed the Kabechenong/Rivière de Taronto the “Humber River.”

In 1834, when York, now the capital of Upper Canada, was incorporated as a city, the “original name given by the natives of the soil” was preferred – even though Toronto had referred to fishing weirs, a lake, a river, a portage route, and a French fort all some distance away, and never to the site of York itself. Also, the Mohawks, from whose language the name tkaronto derived, had never lived in the Toronto area.

So, the naming of Toronto was based on an escalating series of settler misunderstandings. Still, you have to say, “Toronto” is a catchy sort of name!