98. Today’s hike is roughly 4.0 km from point A in Exhibition Place to point B near the foot of the CN Tower. However, you’ll want to make several deviations from the Martin Goodman Trail (MGT) to visit nearby sights, and you should at least sample the William G. Davis Trail through Trillium Park. Set aside half a day to get the best out of this hike. It’s costly and difficult to park near the CN Tower. Better to park near point A and then return by public transit if you don’t want to go the whole distance there and back. The extensive Ps at Exhibition Place are $18 per day and those at Ontario Place are $15 per day.

Note: the pedestrian bridge (see #101 below) that I used to get from Exhibition Place to Ontario Place has since been closed. Instead use the bailey bridge to the west (see #91 above).

99. Let’s look at two westward views of the surroundings taken from an upper floor of Hotel X in the Exhibition Grounds. BMO Field (above) is the home of both Toronto FC of Major League Soccer (MLS), and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL). Opened in 2007, the stadium currently holds 31,000 and occupies the centre of Exhibition Place. It’s been chosen as one of only two Canadian venues for the 2026 FIFA World Cup of soccer, when its capacity will be temporarily increased to 45,700. Average attendance at Toronto FC games in 2023 was 25,310, while that at Argonauts games was 15,984. So pro soccer is now a far bigger draw in Toronto than the much older-established Canadian version of American football.

100. This evening panorama shows the area a little to the south of #99 above. The huge parking lots surrounding BMO Field are bordered by Lake Shore Boulevard West. Between it and the Lake sits Ontario Place (more at #103 below). As in #99 above, the skyline on the horizon is that of the Humber Bay Shores condo development.

101. Let’s now return to the waterfront. The pedestrian bridge from Exhibition Place over Lake Shore Blvd. to Ontario Place doesn’t look very inviting, but I’ll take it anyway. Note: this bridge has been closed off for the foreseeable future while reconstruction takes place at Ontario Place. Let’s hope that includes a lick of paint for the bridge’s metalwork.

102. The view to the west from the bridge at #101 above. From left to right: Humber Bay (Lake Ontario); the Martin Goodman Trail; Lake Shore Boulevard West; (at rear) the Humber Bay Shores condo skyline; the ExPlace Wind Turbine; (at right front) the Ontario Drive entry to Exhibition Place.

The solo wind turbine at Exhibition Place has been there since 2002, when it was the first such structure to have been sited in a North American city. It stands 65 metres tall (or 91 m if you include a vertical rotor blade), weighs 120 tonnes, cost $1.6M to construct, and generates 600+ kilowatts in winds of 19 km/h, supplying an average of 1,000 megawatt/hours to the city’s grid, enough to power 108 homes. Two additional turbines planned for Exhibition Place were axed, however. It was found to be more energy efficient to put solar panels on the roofs of Ex buildings.

Do these windmills massacre birds, as reputed? An ornithological survey in 2004 found that avian mortality caused by this particular turbine was insignificant compared to that from the glass curtain walls of nearby tall buildings.

103. A map of Ontario Place as it was before recent reconstruction closed off most of it. The still open Trillium Park (see #104 below) is on the eastern shore of the east island.

In the 1960s, Montreal, then the largest and most dynamic Canadian city, had embraced cutting-edge architecture. Its highly successful World’s Fair, Expo ’67, had showcased such imaginative structures as Moshe Safdie’s Habitat, Buckminster Fuller’s US Pavilion (now the Biosphère), and Rod Robbie’s Canada Pavilion. Much of Expo ‘67 was built on the artificial Île Notre-Dame in middle of the St. Lawrence River.

In 1971, Ontario Place was Toronto’s attempt to match its main urban rival. Five steel and glass multilevel pods were perched on pylons embedded in the Lake, suspended by steel cables, and connected to each other by walkways. These were intended as a permanent home for exhibitions about the province of Ontario, as well as the centre of a theme park occupying three small artificial islands. The Cinesphere, the first theatre specifically built to show the new IMAX films, also opened in 1971. Its design mirrored the geodesic Biosphère. Among other attractions, there was the Forum, an outdoor stage for free concerts, and there was a Children’s Village. Another outdoor concert venue, Echo Beach, was added in 2011.

The more striking Ontario Place buildings, designed by Toronto architects Craig, Zeidler and Strong, won numerous architectural awards. But overall attendance was always below expectation and the facility ran a deficit from the beginning. The Children’s Village lasted only to 2002. In 1994 the Forum was demolished and replaced by the unremarkable Molson Amphitheatre, now the Budweiser Stage, a 16,000 capacity ticketed outdoor music venue. In 1995 the pods were closed to the public and rebranded as Atlantis, a venue available to private renters. But still the facility didn’t thrive and by 2016 only the Molson Amphitheatre, the Cinesphere, and Echo Beach were still operational. The pods and the Cinesphere are currently out of commission for an unspecified period while reconstruction takes place.

It’s hard to foresee the future of Ontario Place. There’s a controversial plan to site a Therme Spa (with admission starting at $40) on the west island. This plan is strongly resisted by those who want all three islands to be freely accessible to the public. There’s also a plan to relocate the Ontario Science Centre in North York to Ontario Place. Contrary to some reports, the Ontario Line, a new subway due to open in 2031, will have its southern terminus at Exhibition Station, not at Ontario Place. The Ontario Line’s northern terminus will be at the current Ontario Science Centre … which may by then have moved to the waterfront!

Trillium Park, meanwhile, is open, accessible, free to enter, and probably the template for how Ontario Place should be developed.

104. Trillium Park occupies the eastern edge of the Ontario Place complex, and is definitely worth a visit. There’s plenty to see on the William G. Davis loop trail through landscaped parkland.

These Anishinaabe moccasins are carved into the granite wall of an artificial ravine. They’re based on the drawings of Indigenous artist Philip Cote of 500-year-old moccasins housed at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto. They’re part of the Moccasin Identifier project envisioned by Carolyn King, former Chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. Her idea was to place representations of moccasins associated with different First Nations in significant locations all over Canada. These would remind people of the original presence of Indigenous peoples and their intimate connection, literal and symbolic, to the land.

105. Indigenous Toronto-based artist Keitha Keeshig-Tobias Biizindam decorated this shipping container with a mural entitled “An Anishinaabe Kwe’s Dream-Catcher,” on temporary display in Trillium Park. On the shorter side (right) titled “Culture Back,” the mother’s hair is shaped like a dream-catcher to stop the nightmares of First Nations’ post-colonial experience from reaching her infant. The longer side, “Land Back,” shows the molecular structures of medically useful substances familiar to First Nations of the Americas before contact with white settlers. They include curare (as an anaesthetic), benzoylmethylecgonine (as a stimulant), quinine (as an anti-malarial), populin (as an anti-inflammatory), theobromine (as a bronchodilator), vitamin C, and salicylic acid (as natural aspirin).

106. From Trillium Park there is a spectacular view of the downtown Toronto skyline over the marina of the National Yacht Club. The white arched structure at centre is the roof of Rogers Centre (see #129 below).

107. There’s also a good view of aircraft movements at Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport (YTZ). This is a small but busy airport named for Canada’s greatest WWI flying ace (1894-1956) and located on the northwestern part of Centre Island. The Island Airport, as it used to be called, has been around since 1939, but business has only taken off, so to speak, in recent years. In 2022 PAX increased an amazing 514% over the previous (pandemic) year, and at 1,732,00 passengers it was the 9th busiest airport in Canada.

YTZ serves about 20 destinations in eastern Canada and the US. It has two runways, the longer one only 1,216 metres, which restricts the size and range of aircraft. Passengers access it by a 240 m pedestrian tunnel under the channel separating the island from the mainland, or, if in a vehicle, by a 90-second ferry ride. It should be noted that YTZ is only 2 km from the CN Tower, while Pearson (YYZ), Toronto’s main airport, is 25.5 km away.

Since 2006 the main carrier at YTZ has been Porter Airlines. It operates a fleet of turboprops, as jet aircraft are banned from YTZ and an 11:00 pm curfew imposed, to cut down on noise for local residents.

[Top] The control tower and a pair of parked floatplanes at Billy Bishop. They’re Cessnas, a 206 and a 208 owned by Cameron Air Service, offering speedy if pricey trips up north to the lakeside cottage.

[Bottom] A De Havilland (formerly Bombardier) Canada Dash 8-400 operated by Porter Airlines lands on the main runway at Billy Bishop.

108. Trillium Park is also a good place to go jogging, watch sunsets, or do both at the same time.

109. Back on the mainland, the Toronto Inukshuk, 9 metres tall, looms over Inukshuk Park. Kellypalik Qimirpik (1948-2017), an Inuit sculptor from Cape Dorset, Nunavut, constructed it from 50 tonnes of Ontario rose granite to commemorate World Youth Day and the visit to Toronto of Pope John Paul II in 2002.

Inuksuit (the plural of inukshuk) are constructions of piled stones made by the Inuit and other Arctic First Nations as navigational signposts. An inukshuk like the one above is properly called an inunnguaq (“imitation of a person”) as it specifically represents the human form, and originally had a more spiritual meaning than a plain inukshuk. Smaller inunnguat are now found everywhere in Canada where there are stones to be piled, reminders of the country’s ancient First Nations heritage.

At Inukshuk Park the Martin Goodman Trail splits into two branches, one running along the north edge of Coronation Park, the other hugging the lakeshore.

110. The northern branch of the MGT takes us to the monumental Princes’ Gate (Strachan Ave. at Lake Shore Blvd. W.) standing at the eastern entrance to Exhibition Place. Constructed in 1927, it was designed by the Toronto architects Chapman and Oxley, also responsible for the Hudson’s Bay department store on Queen Street West and the expansion wing of the Royal Ontario Museum. The statue holding a laurel wreath on top of the central arch was inspired by the 2nd century BC statue of Niké, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, in the Louvre. The male statues surmounting the columns personify Canadian agriculture.

You can’t help noticing the striking contrast between the grandiose gate and what lies through it. As the Toronto Star recently put it, “Entering the imposing and impressive Princes’ Gates archway flanked with colonnades and topped with Roman-style sculptures, the initial impression of the site is promising. Yet, as you venture further into Exhibition Place you’re struck with how desolate it feels: there’s no one walking around, not one shop or café” (26 December 2023).

The current CEO of Exhibition Place wants to avoid this kind of visitor disappointment. He envisions a promenade lined with trees, lighting and benches, designated bicycle lanes to improve public access for pedestrians and cyclists, public art, video boards, and a year-round food hall.

111. The next tract of greenery to the east is Coronation Park. It’s named for the 1937 coronation of King George VI, when 144 saplings were planted here by Canadian WWI veterans to commemorate their sacrifice. The contemporary aerial photo below shows where the trees were planted, with the Princes’ Gates at the west end.

During the visit of George and Elizabeth to Toronto in 1939 (see #68) 123 sugar maples were planted on the curved road near the water’s edge, each representing one of the city’s schools. As the King and Queen were driven down Remembrance Drive, WWI veterans held the young trees steady while students shovelled soil onto their roots.

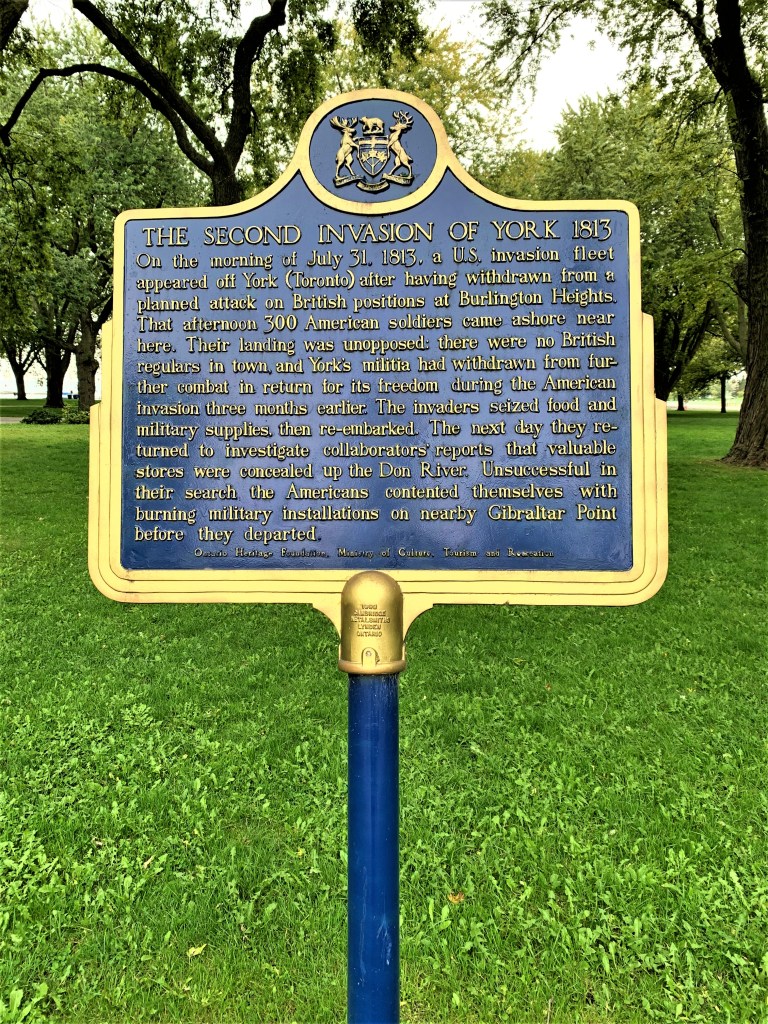

112. The blue historical plaque in Coronation Park (top) gives me an excuse to reproduce Owen Staples’s painting (1914; bottom) of the First Invasion of York by the American fleet on 27 April 1813, three months earlier. This was a much more significant event during the War of 1812, one that resulted in the American capture of York and the explosion of the Fort’s powder magazine that killed many men on both sides. The Americans withdrew on 8 May, as York in those days wasn’t important enough to hold on to. (They withdrew even sooner on the second occasion in July. And they attacked York for a third time in August 1814, but this time the garrison held off the invaders.)

At the centre of the painting, Fort York is where the red flag is flying. (It’s now a National Historic Site due north of Coronation Park.) The town of York, the embryo of Toronto, about 2.5 km to the east of the Fort, is not clearly represented in the painting, though the northern course of Yonge Street and the west-east course of what was then Dundas Street can be seen. The Gibraltar Point referred to on the plaque is where the lighthouse sits offshore on what is now Centre Island.

Note: as the painting shows, the shoreline of Lake Ontario in 1813 was immediately below the rise on which Fort York sat. It’s now about 600 metres as the crow flies from the Fort to the lakeshore at Coronation Park. All the intermediate land, including the course of the MGT between the Humber and Don Rivers, has been artificially reclaimed from the Lake over the years. And likewise much of the northwestern part of Centre Island, where Billy Bishop Airport now sits.

113. The Victory-Peace Monument stands near the shore in Coronation Park. Designed by Toronto artist John McEwan, its installation and dedication in November 1995 marked the 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. There are two pairs of standing curved bronzes (e.g., top) on which are inscribed text, maps, and symbols (middle). The sculptor calls these bronzes “Gates … in the form of a sprit-bow of ship,” one signifying the departure of troops and the other their return. Between them there’s a brass disk on the ground (bottom) on which are inscribed the words for “peace” in several languages and around which there are steps, making a miniature amphitheatre.

Given its history, Coronation Park is a fitting setting for a WWII memorial. However, I mean no disrespect to those who fought and died in that war when I say that this memorial is too abstract and too incoherent. Can an average person recognize these bronzes as “Gates” and understand what they represent without being told? While peace may be universally desired, it sadly does not exist at the heart of war, though the disk seems to suggest the opposite. And victories against tyranny are achieved by dedicated people working together. Shouldn’t a WWII memorial include representative images of Canadians who helped defeat tyranny and restore peace?

114. HMCS York occupies a plot in the eastern part of Coronation Park, opposite the National Yacht Club. The MGT passes it to the east before it turns onto Queens Quay West. H[is] M[ajesty’s] C[anadian] S[hip] York is what’s referred to as a “stone frigate,” namely a shore-based naval training facility. In this case it recruits and trains the part-time sailors of the Canadian Naval Reserve. The building houses about 350 officers and part-time sailors.

115. A worker cleans windows at Tip Top Lofts, a heritage former industrial building on the other side of the MGT from HMCS York. It was once the HQ of Tip Top Tailors, a Toronto menswear retailer, and has some fine Art Deco detailing, thankfully preserved. Six storeys were added to the five of the original 1929 building to make a condominium containing 256 units of varying size. The original neon TIP TOP TAILORS sign remains on the roof. There are still Tip Top Tailors stores across Canada, though they’re now owned by Gordon Brothers of Boston, MA.

116. Little Norway Park is the next green space on the MGT. It was created in 1986 on the site of a WWII Royal Norwegian Air Force training camp. The camp had been established on this site near the Island Airport in 1940, after Norway had been invaded by Nazi Germany. More than 2,000 exiled Norwegian airmen were trained in Canada and sent to the UK to help the Allied war effort. The odd “creature” depicted above is a boulder transported from Norway to this site in 1976, and rather incongruously given pebble “feet.” The only surviving artifact from the camp on site is the base of a flagpole.

117. Little Norway Park contains this installation, “Dreamwork of the Whales,” exquisitely carved from a 40-foot western red cedar. It’s not a totem pole, though it has clearly been influenced by West Coast Indigenous art. Georganna Malloff (1936-2022) of Campbell River, BC, designed this as the second of her 20 “Cosmic Maypoles.” There is no information about it on site, but I was able to find some online. The pole was produced by Ne Chi Zu Works, a group of Toronto-born artists living in Vancouver, who retained Malloff to create the overall design. A 700-year-old tree was trucked from British Columbia to Toronto and transformed by apprentice and mature woodcarvers, some of whom were Indigenous, under Maloff’s supervision. All donated over four unpaid months to shape the pole. It was raised by 300 volunteers on 13 October 1981. The link above includes comments by Malloff about her role as designer.

118. Little Norway Park has been a site for First Nations protest. When I visited, the fence at the back of the park’s baseball diamond displayed this moving unofficial memorial to the First Nations children who suffered and sometimes died at the hands of the self-styled religious authorities administering Canada’s ill-conceived and now notorious Residential School program (1831-1996).

119. Eireann Quay, a road down the east side of Little Norway Park, leads to the modest landside entrance to Billy Bishop Airport.

120. A youthful crew are shooting a video on a lawn in Little Norway Park.

121. The hulking former Canada Malting Company silos on Eireann Quay at the foot of Bathurst Street. The concrete silos were built in 1928 and have been empty since 1987, but as designated heritage buildings they cannot be demolished. There were once plans to turn them into a music or civic history museum, but these fell through. Meanwhile a new park, Bathurst Quay Common, including a sun deck and event plaza, is currently close to completion on the lake side of the silos.

These buildings recall a time when large breweries, the chief clients for malt, dominated Toronto’s downtown. (Malt is cereal, usually barley, that has been water-steeped, germinated, toasted, then smoked. It’s used in brewing beer, making vinegar, and distilling whisky.) Meanwhile, Canada Malting Co., founded in 1902, is still very much in business, owning major malthouses in Calgary, Thunder Bay, and Montreal.

When questioned about the current plans for this silo complex, a City of Toronto spokesperson responded: “Ambient uplighting for the iconic malting silos … will transform these restored, landmark structures into an architectural beacon marking the western entrance to Toronto’s harbour.” The silos are a reminder of central Toronto’s industrial past. But the City’s language reveals just how profoundly post-industrial is its present.

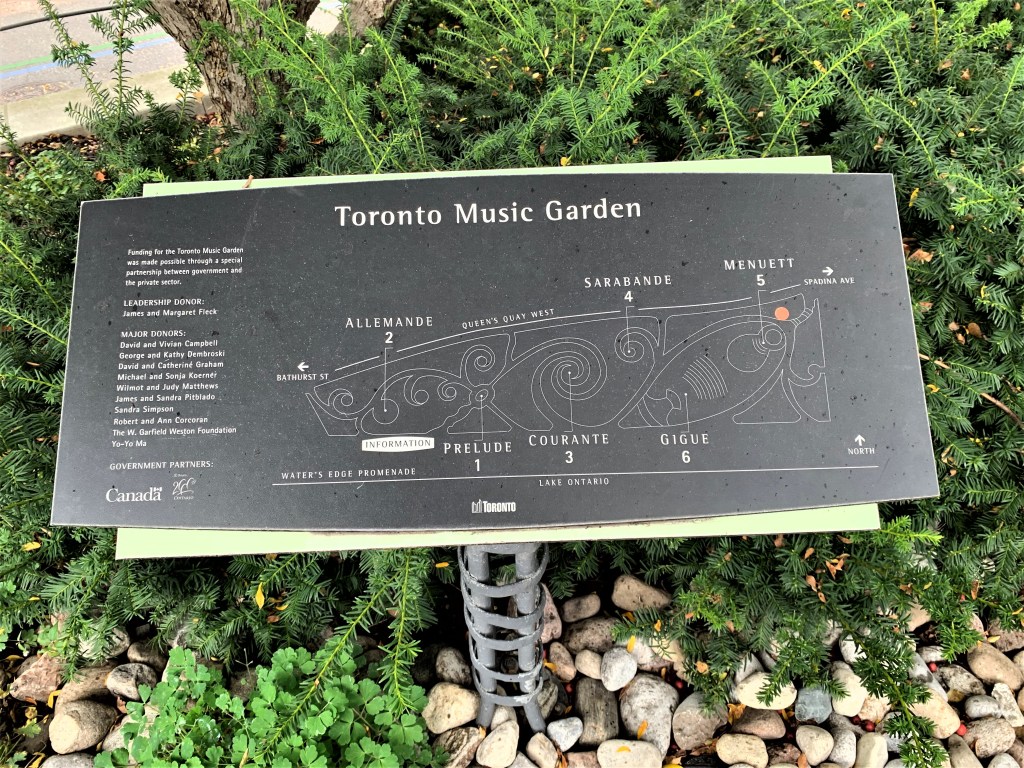

122. The Toronto Music Garden takes up much of the waterfront between Bathurst Quay and the south end of Spadina Avenue. And very lovely it is, especially in the flowering season. The Garden owes its origin to the cellist Yo-Yo Ma (b. 1955). He’d made a series of six films (Inspired by Bach, 1997-98) each based on one of J.S. Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello, of which he is the foremost living interpreter. In the first film, The Music Garden, Ma works with landscape designer Julie Moir Messervy to design a garden based on the 1st Suite in G major (BWV 1007). The city of Boston is chosen as the location to embody the film’s ideas in an actual urban garden, but plans fall through and Toronto takes up the challenge.

As the plaque indicates, the Garden has six areas. Each is named for a movement of the 1st Cello Suite …

123. … so, a wildflower meadow with a metal structure at the centre is the swirling third movement (Courante) …

124. … while the sixth movement (Gigue) is represented by a grassy set of steps that forms an amphitheatre for concerts.

125. In early fall, the beauty of the Music Garden is more in the details than in the overarching structure.

126. The great cellist himself is celebrated in the name of a laneway on the north side of Queens Quay West.

127. To the east of the Music Garden is the Spadina Quay Wetland. This small site is a former lakeside parking lot that began to be naturalized in 1999, after a fisherman discovered northern pike spawning near here. It now harbours a diverse ecosystem including birds, fish, butterflies, and amphibians. But how to incorporate a messy, weed-overgrown marsh into the urban fabric? Paths, a boardwalk, and viewing sites have been thoughtfully laid out, and information boards provided. Birders have spotted 90 different species here over the past five years. The birdhouse above, incorporating miniature versions of the Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion (see #75 above) and other local landmarks, stands in the centre of the marsh.

128. Empire Sandy, the largest tall ship in Canada, is docked at the Spadina Slip. A 740-ton steel-hulled topsail schooner, she’s 61.9 metres long and can carry up to 1,022 square metres of sail on her three 35 metre masts. With room for 275 passengers and a crew of 25, she’s available for public cruises and private charters on the lake.

Hard to imagine, but she was built as a deepsea tugboat in 1943 at a shipyard in northeast England and saw a great deal of active service during WWII. After the war, she was sold to a Canadian firm and, renamed Chris M, spent some years towing timber rafts on Lake Superior. As her steel hull had remained sound, she was converted to a schooner in 1982, given back her original name, and now you’d never know this elegant sailing vessel was once a tugboat.

129. We turn northward up Rees Street, and in less than 5 minutes we’re outside the Rogers Centre, Toronto’s Major League Baseball stadium, home of the Blue Jays of the American League East. Its architect was the same Rod Robbie who designed Ontario Place. Completed in 1989 as the SkyDome, it was renamed in 2005 for the telecom corporation that owns the Blue Jays. It has a retractable roof, a hotel onsite, and can seat 41,500 for baseball games.

130. The CN Tower stands just to the east of Rogers Centre. It’s Toronto’s most recognizable structure and stands at the midway point of our Waterfront hike. We’ll finish this leg at its foot.

The CN Tower is 553.3 metres high (1,815.3 ft), which is roughly the horizontal distance between it and the lakeshore. The architects were Webb Zerafa Menkès Housden of Toronto, also responsible for the Bay-Adelaide Centre and Royal Bank Plaza. When completed in 1976 it was the world’s tallest freestanding structure, though it has since been surpassed by towers in China and Japan, as well as by a few supertall skyscrapers like the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Essentially, it’s a communications tower and very popular visitor attraction. The main pod contains several observation decks and a revolving restaurant at 351 m, the latter being the world’s highest. Visitors can go higher still, to the SkyPod at 447 m. This sits below the 102 m metal spire, an antenna used for broadcasting TV, radio, and cellphone signals. The concrete shaft of the tower is hollow and accommodates six elevators and a staircase.

If you’re not afraid of heights and have a healthy bank balance you can do the EdgeWalk, which involves circling the outside top edge of the main pod at 356 m. For this you wear a special EdgeWalk suit and harness to stop you from falling, and you get a photo and certificate to prove you’ve done it.