84. From the Belwood Bridge looking downstream.

You could say that a river is a channel of largely colorless and tasteless inorganic liquid impelled downhill by gravity until it disappears into a larger body of the same stuff.

But that’s to miss everything that makes a river important. Water is the essential element of all known forms of terrestrial life. Though it may not be literally alive itself, a river both contains and sustains innumerable living creatures, whose survival is dependent on the river’s well-being. A river is in constant motion, reacting to local conditions in ways that that can be disastrous if not anticipated by the humbler entities in its vicinity. Like Time itself, a river is a unidirectional continuum, all parts of which are connected by a remorseless chain of cause and effect. Like Time, a river is unaffected by human wishful thinking.

Early settlers saw the Grand River in utilitarian terms. It turned their mill wheels or carried their logs downstream. When its banks had been clear cut, and when steam engines had replaced water power, the Grand became chiefly a chute for sewage, industrial effluent, and garbage. Those upstream had little thought for the downstream consequences of their actions.

Fortunately, our thinking has changed, though it took years to raise our consciousness in this regard. These days the Grand runs relatively clear … most of the time.

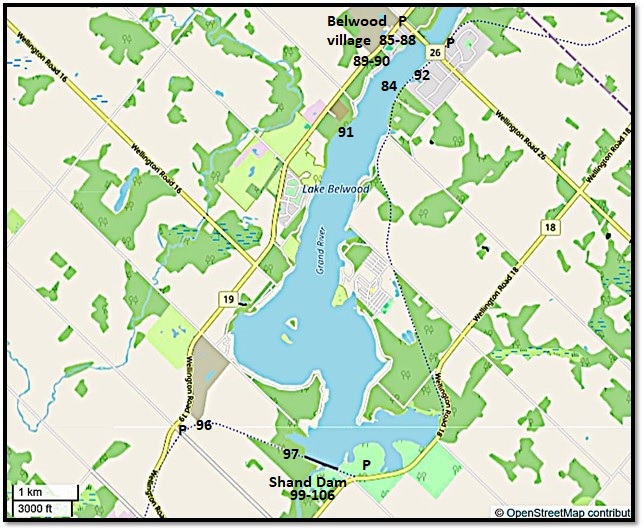

Map 10. Lake Belwood*

Lake Belwood is a reservoir created by damming the Grand River. It’s about 7 km as the wild duck flies from the Belwood Bridge to the Shand Dam. In the summer, the upper Lake south of the Bridge is roughly 500 metres across, while the lower Lake widens to about 2 km in two places. In the off-season, the Lake is allowed to slowly drain away through the Dam.

You can hike or bike the eastern and southern sides of the Lake on the Elora Cataract Trailway (ECT). Or you can hike the western side on the Grand Valley Trail (GVT), though this involves a spell on the side of County Road 19. It’s about 19 km around the whole Lake. If you’re determined to do a circuit, better to do it by bike, using roads on the west side.

You can park (P) your car in the Belwood Lake Conservation Area, where the fee is currently $8.50 per adult for day use if an attendant is present, or $17.00 per vehicle with an ePass if the attendant is absent. Or you can P for free at the roadside in Belwood village or in the few available spots where the ECT meets 2nd Line.

*Lake Belwood or Belwood Lake? According to the Canadian Geographical Names Database, the official name is Lake Belwood, but for unclear reasons the Grand River Conservation Authority prefers Belwood Lake.

85. We’ll start in Belwood village. The tone of the inscription on the plaque is slightly resentful, but this is to be expected. About half the houses and most of the business section of Belwood disappeared under the reservoir that was created as part of the 1939-42 water control measures along the Grand River (see #102 below). Only two houses were moved to higher ground, as most owners chose to sell their houses to the Grand River Conservation Commission (as it was then) and move away. Belwood’s current population is about 470, not much more than in 1885.

Belwood may have been named for an area in Penicuick, Scotland, not far from Edinburgh. The Scottish influence on this area was considerable.

86. You can buy essential supplies including sandwiches to order at the Belwood Country Market, here tricked out for Halloween. Seize the opportunity: the next nearest store is miles away in Fergus.

87. St. John’s United Church (1872-73) on Queen Street in Belwood. This little stone building survived the creation of Lake Belwood.

It was built as a Presbyterian church. Such was the Scottish Low Church tradition, no music was allowed in services. “They thought it was the work of the devil … and so all the singing was done a cappella and they had a cantor to lead the singing, not a choir and they had just a tuning fork,” said Rev. Kate Gregory, the current minister. When an organ was introduced in 1878, many members left in protest.

88. Taking their cue from the Bruce Tail, the Grand Valley Trail Association erected this cairn on George Street by Maple Park in Belwood to mark the northerly terminus of the Grand Valley Trail.

From here, the GVT goes along the western side of Belwood Lake, then joins the Elora Cataract Trailway into Fergus. The whole GVT is about 240 km long and terminates at Port Maitland, near where the Grand River debouches into Lake Erie. As much of the Grand is in private hands, a lot of the GVT is on public roads, so an end-to-end better suits cyclists than hikers. But here in Belwood the GVT has a good start …

89. … though it’s a bit tricky to find. Cross Maple Park and the baseball diamond to the west of it, and look for the Trail’s entrance in the woods behind, where there’s a little boardwalk and a faded sign. Then follow the directional white blazes, also borrowed from the Bruce Trail. The path through the woods is very pleasant for a couple of kilometres. It’s currently well blazed, though your path may be hampered by fallen timber. You can’t really get lost, as you can glimpse the Lake through the trees on your left, and hear traffic on busy County Road 19 on your right.

90. In mid-October the colour is mainly provided by fallen leaves. But a hint of purple drew my attention to this hardy little selfheal (Prunella vulgaris) still in bloom at the edge of the Trail.

91. The Trail will take you past the lakeside cottages, after which you can get down to the water’s edge on an unmarked side trail. You’re likely to find yourself entirely alone. This beach offers a beautiful cloudscape over the south end of the Lake.

As the GVT now gets less interesting, let’s return to Belwood village, cross the Bridge, and sample the ECT on the other side of the Lake.

92. The ECT goes from Elora via Belwood to the Forks of the Credit River. The Belwood section begins at the east end of the Belwood Bridge, where there is a free P on Sideroad 10, and skirts the east and south sides of Lake Belwood. This is another of the rail trails that partly compensate for the loss of train service in the valley of the Grand.

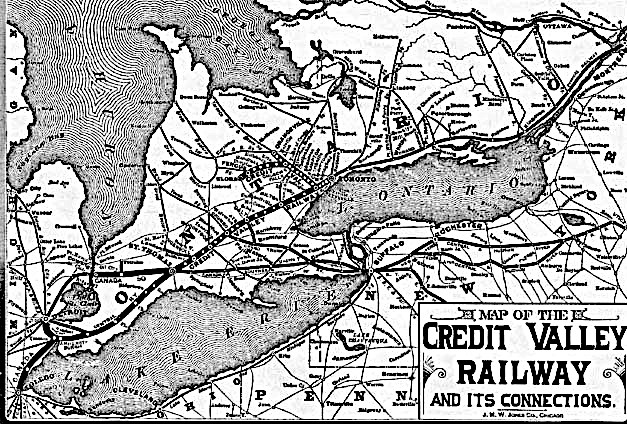

93. Belwood was once connected to Toronto by a train that ran twice a day and took just over three hours. The first train to stop in Belwood did so on 17 December 1879. It was on a 27.5-mile-long branch of the Credit Valley Railway (CVR) that left the Toronto to Orangeville line at Church’s Falls (now called Cataract) and went through Erin, Hillsburgh, Orton, Belwood (then called Douglas) and Fergus, ending at Elora, where there was a turntable so the locomotive could reverse itself. This Elora branch line was never busy or profitable.

The CVR, like the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway (see #52 and #63 above), was taken over by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1884. Passenger trains on this branch line were discontinued in 1968, the line was abandoned in 1988, dismantled in 1993, and it’s now a 47 km rail trail.

For further information, see Will Annand’s chapter on the Branch Line in Credit Valley Railway: A History.

94. A lakeside house with “the works” on the west side of the upper Lake, as viewed from the Trailway. From left to right: a gazebo with mosquito screens, kiddie paddling pools, an SUV, a Tempest fishing boat at the private dock, an array of Muskoka/Adirondack chairs by the firepit and at back for contemplating sunsets on the lakeside lawn, a barbecue with furled protective umbrella on the back deck, an ATV under wraps, inflatable kayaks, a boat trailer carrying a windsurfing catamaran.

Once the Lake is drained in the off-season, the shoreline will recede some distance from here.

95. You’ll definitely want to visit the Shand Dam at the south end of the Lake. The easiest way to do so is to drive to the Belwood Lake Conservation Area on Wellington Road 18 at 3rd Line, pay the entry fee (rather exorbitant given that the Dam can be visited in half an hour), and park right by the Dam.

This Conservation Area is intended for picnics, beach activities, and boat launching. If you hike or bike along the ECT from the Belwood Bridge, you can view the Dam for free, but it’s 8.1 km along the Trailway and you have to return the same way. The charming forested GVT hike along the west side of the Lake that I describe in #89 above soon becomes neither charming nor forested, and it’s over 9 km one way. So…

96. … if you want to visit the Dam for free and get some exercise without totally exhausting yourself, P on 2nd Line at Spier and walk or bike the 2.3 km east along the ECT. It’s an easy and popular ride, so if you’re on foot, keep checking behind you for oncoming cyclists. Some riders are a bit wobbly, others not too respectful of mere pedestrians. You’ll have to retrace your steps when you leave the Dam, so your hike will be about 4.6 km.

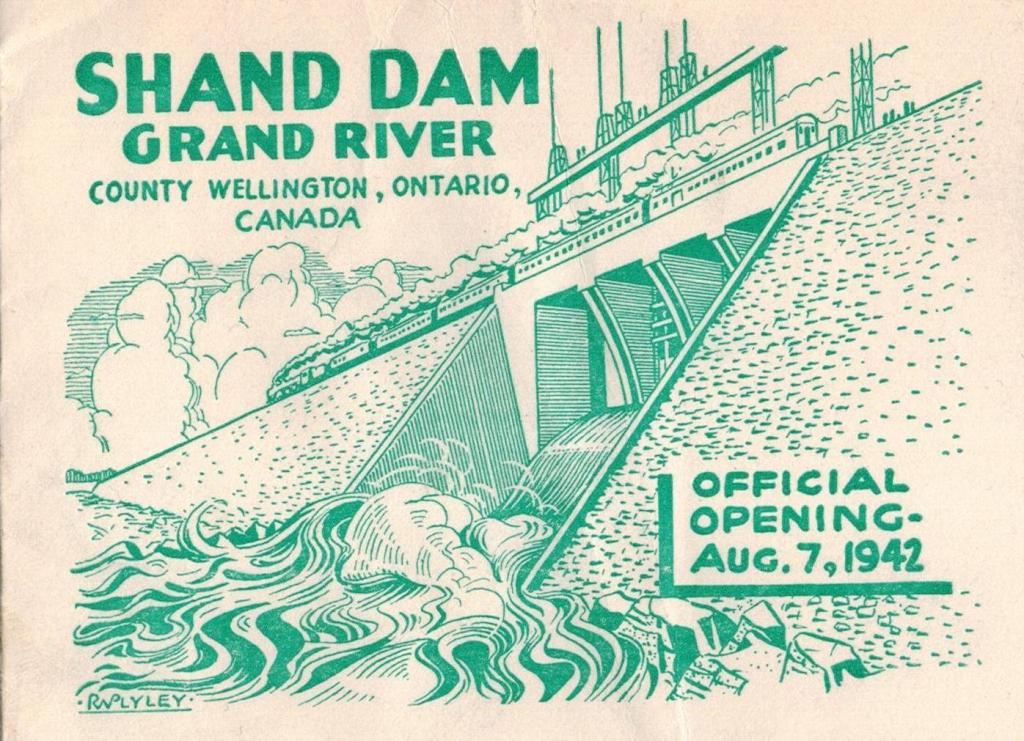

97. We’re approaching the top of the Dam along the ECT from Spier. As this Trail was formerly a rail bed, you’ll realize that trains used to go right over the Dam …

98. … as this image announcing the official opening of the Dam makes dramatically clear!

99. This is the view from the Dam northeast across one of the widest parts of the Lake.

100. You can fish Lake Belwood for northern pike, perch, walleye, carp, and smallmouth bass. Though most of the Lake is shallow most of the time, lifejackets are recommended for boaters, especially if you’re easily distracted by your cell phone or if your tiny inflatable kayak is inherently unstable.

101. From the ECT along the top of the Dam you can descend this long set of steps …

102. … 23 metres down to the riverbank below the Dam.

The Shand Dam has four adjustable gates opened according to the need to regulate flow. The eight tall posts above the dam are screws allowing the gates to be opened and shut.

There are seven dams in the Grand watershed, at Luther (see #29 above), Conestogo, Laurel Creek, Shade’s Mills, Woolwich, Guelph, and here. The Shand Dam is the largest, with a holding capacity of 63.9 million cubic litres and it’s the only one on the Grand River itself. All the rest are on tributaries.

The Shand Dam is primarily a water control structure. It holds back water to reduce flooding downstream during spring thaw and after heavy rain, and in dry summers it releases water gradually from Lake Belwood so that the Grand downstream doesn’t dry up. Before the Dam, the Grand would alternate annually between extremes: a raging torrent causing widespread flooding in spring and fall, and a trickling, stinking sewer in the summer.

The flooding on the Grand is well documented, but the other extreme was almost as bad. In the mid-19th century “the river became a repository for anything that could not be disposed of conveniently by other methods. Distilleries were located on the banks of the river at Elora and Fergus; these fed their spent mash to cattle in adjoining feedlots, and rains then washed the manure into the river. Bakers in Elora and Fergus dumped their stale bread into the water, and butchers used the same method for tainted meat and rancid fat. As well, there were the various by-products of the factories: dyes, chemicals, scrap and garbage. The Irvine River at Elora served for a time as a dump for household garbage, ashes, and even dead livestock. Most of the time, all this refuse quickly floated downstream, but in summer, when the water behind the dams became stagnant, the Grand River became a series of bubbling cesspools.” From Steve Thorning, “Development and the Upper Grand River before 1938,” 19.

103. The view from the top of the Dam looking almost vertically down.

Construction on the Dam began in 1939 and was completed in August 1942. Shand is an earthen embankment dam with a stilling basin. Those baffle blocks in a line at the foot of the Dam cause water to slow down after release. In 1987 a hydroelectric generating turbine was installed in the Dam. It now can generate a maximum of 690 kW, enough to power 500 homes. The turbine has its own outlet at the level of the riverbed.

104. As the Shand Dam releases colder water from the bottom of the reservoir, the Grand immediately downstream from it is an excellent brown trout fishery. You can also fish here in the Shand tailwater for smallmouth bass, pike, bullhead, and walleye.

105. This great blue heron also appreciates the excellent fishing in the turbulent waters by the foot of the Dam.

106. The view from the top of the Dam downstream. Let’s remind ourselves of what the Grand around here looked like before water control:

“In the summer of 1936, the Grand River dried up completely upstream from Fergus. Downstream, virtually the entire flow consisted of sewage effluent. The following February, the river compensated by offering one of the worst floods in its history. The river rose about 12 feet above its normal level in Elora; more than that through the narrow confines of its course through downtown Fergus. The damage of previous floods was repeated, with the worst being felt in the downstream towns. As an encore, the river offered a second, less severe flood in the aftermath of an early June rainstorm…. In June, 1937… Premier Hepburn made a fresh approach to the federal government for aid in getting the Grand River project into active construction. Early in 1938 the Ontario Legislature passed the Grand River Act, creating the Grand River Conservation Commission, and providing a cost sharing formula: one quarter by the municipalities, with the remainder divided equally between the federal and provincial governments.” Thorning, op. cit. at #102 above, 27.

At long last it was acknowledged at the political level that the management of a big river requires continuous collaboration between those communities it connects.

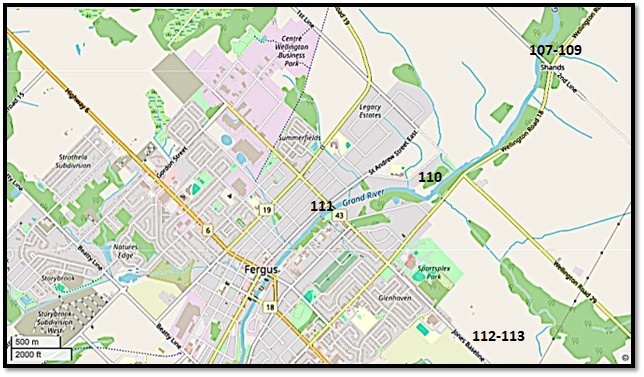

Map 11: Shands to Fergus

This map shows Shands (top right) where 2nd Line crosses the Grand; Pierpoint Park on the edge of Fergus; and Jones Baseline, a.k.a. County Road 43, crossing Fergus from the northwest to the southeast. In central Fergus, Jones Baseline is called Gartshore Street and, farther south, Scotland Street.

107. The next bridge over the Grand, the first vehicular one after Belwood, is on 2nd Line at Shands.

108. Though the riverbank here is on private land, the landowner commendably provides a metal staircase for anglers to access the east bank. A sign from the Friends of the Grand River invites anglers to participate in a fishery survey run by the University of Guelph.

109. The view upstream from the 2nd Line bridge is charming, but be careful when checking it out … there’s no shoulder or sidewalk on the bridge.

110. We’ll head into Fergus via County Road 19 along the north bank of the Grand. We turn down Anderson Street towards the River and then into the small P near the junction with Lamond Street. This is Pierpoint Park, a small overgrown wilderness area (top) that fly fishers must wade through to get to the riverbank.

As the faded information board (bottom) indicates, there’s an interesting history to this bit of land. Richard Pierpoint (ca. 1744–1838), born in French Senegal, West Africa, was kidnapped at the age of 16 and shipped into slavery in the American colonies. He must have escaped from bondage into British North America during the turmoil of the American Revolution, as he fought as an Empire Loyalist – one of only eight Blacks – in Butler’s Rangers during the Revolutionary War. Later, at an advanced age, he helped raise the so-called Coloured Corps that fought on the British side in several key conflicts in the War of 1812. He was rewarded with land in what is now St. Catherines, where there is a park named for him.

In 1821 “Captain Dick,” as he was known, petitioned His Majesty’s Government unsuccessfully for a return passage to Africa. Instead, he was granted this land in what was then Garafraxa Township, where he established a small Black settlement several years before the founding of the town of Fergus. He died with no known heirs, and it’s not known where he was buried, though it could be somewhere on this land.

There’s more information about this remarkable man, who lived into his mid-90s, in part 3 of my Hiking the Welland Canal photo blog.

111. The Rubicon was an obscure stream forming the boundary between Rome and Cisalpine Gaul. After Julius Caesar crossed it in 49 BC, it became proverbial for an irrevocable step demanding full commitment, a decisive move that in Caesar’s case led to civil war and his eventual elevation to Roman Dictator.

This is the Caldwell Bridge on Gartshore Street in Fergus, the easternmost of the bridges over the Grand in the town. Standing here on its west side, anyone writing in any depth about the Grand River has crossed a Rubicon. The fiercely contested history of this river’s settlement can no longer be ignored.

The Rubicon is not the river, but the road across it. Follow Gartshore Street south, and it becomes Scotland Street …

112. … and follow Scotland Street a little farther south and here on the edge of the town, still close enough that you can read the name on the water tower …

113. … and you find that it has changed its name to Jones Baseline. This is the Rubicon. To cross it is to enter willy-nilly a centuries’-long debate over who owns, or owned, the Grand River and its valley.

It’s difficult to summarize the issues without simplifying them, and even harder to keep an objective stance without inadvertently giving offence. But having crossed the Jones Baseline I have to try. A lawsuit 40 years in the making about a situation that began 240 years ago, one that seeks staggering amounts of compensation, is about to come before the Ontario Superior Court. So this issue is soon going to capture public attention. As a way of approaching the subject, here are portraits of three men, none of them born in what is now Canada, whose legacy must be addressed.

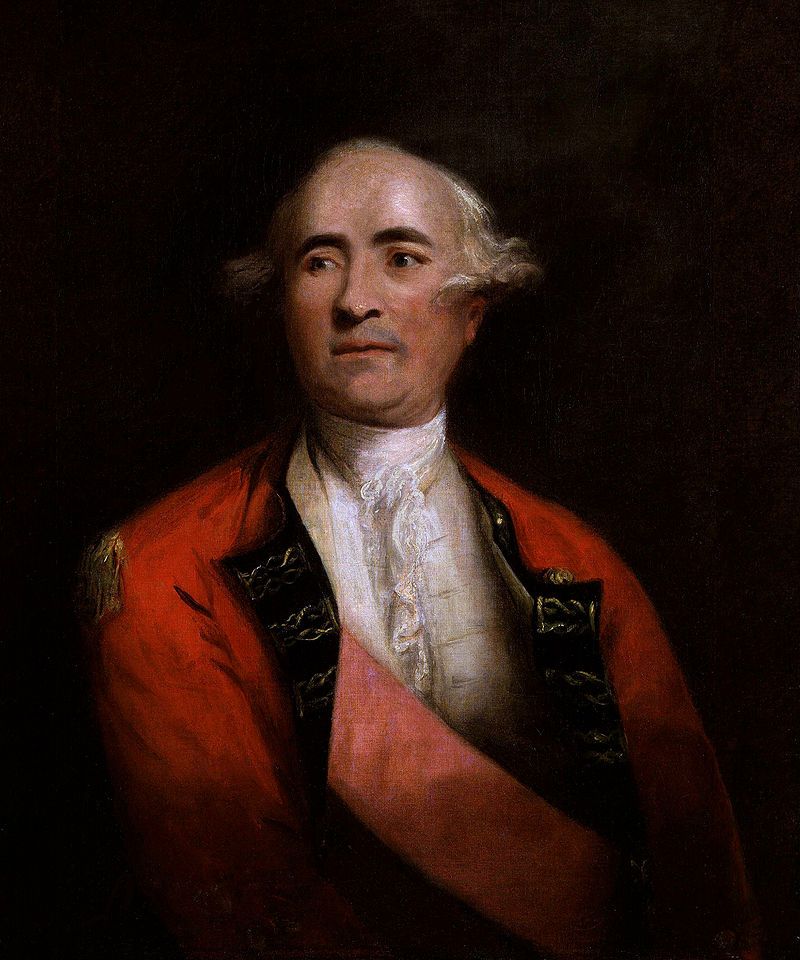

114. Sir Frederick Haldimand (1718-91) was a Swiss-born military officer who served on the losing British side during the American War of Independence. From 1778-86 he was the Governor General of the Province of Quebec, as that part of east-central North America that remained a British colony was then called. (The colony would be divided into Lower Canada, now Québec, and Upper Canada, now Ontario, in December 1791, by which time Haldimand had been dead for six months.)

On 22 May 1784 on behalf of the Crown Haldiman purchased from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation a huge tract of land bounded by Lakes Huron, Erie, and Ontario. The Crown paid the Mississaugas 1,180 pounds 7 shillings 4 pence worth of trade goods for about 3 million acres (12,400 sq. km) of territory that would eventually be the location of such cities as Hamilton, Guelph, Kitchener, Waterloo, Cambridge, Brantford, and St. Catherines. Haldimand believed that the not-yet-surveyed territory would be needed to accommodate the approximately 8,000 white Loyalists pouring into British North America in the aftermath of the American Revolution.

But there were First Nations loyalists too, namely members of the powerful Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy of Six Nations: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. Because the majority of these Nations, whose home territory was on the Mohawk River in upstate New York, had sided with the British during the American Revolution, they were no longer welcome in the USA.

Haldimand understood that, though the Six Nations were not unanimous in their allegiance to the Crown, it was necessary to keep as many of them onside as possible, and not only for the sake of the lucrative fur trade. They were famously fierce warriors that would prove invaluable on the British side in any future disputes with the Americans. (The War of 1812 would prove him entirely correct in this.)

115. Joseph Brant (1743-1807), whose native name was Thayendanegea, was born in the Cuyahoga valley near what is now Akron, Ohio. After his father’s death his mother moved her young family back to traditional territory on the Mohawk River in upstate New York.

Brant’s official title was War Chief of the Mohawk First Nation, thanks to his military exploits on the British side during the Revolutionary War. He won great respect among the colonial administration as an intermediary and interpreter between them and the Six Nations Confederacy. A towering figure in the history of Upper Canada, he will figure frequently in subsequent episodes of “The Grand River of Southern Ontario.”

In post-Revolutionary British North America, it was Joseph Brant who embarrassed Haldimand by continually pointing out that there was no mention of the fate of the Six Nations in the Treaty of Paris (1783) between the Americans and British that concluded the Revolutionary War. It was Brant who detailed for Haldimand the losses the Mohawks had suffered at American hands and why and how they should be specifically compensated for their loyalty to the Crown. It was Brant who first proposed to Haldimand that all the Six Nations be offered land on the Grand River, where they could live together in strength by a river not unlike their lost Mohawk, rather than become dispersed and weak. And it was Brant who, like a latter-day Moses, would lead the Mohawks and their allies to the promised land of the Grand River in 1785.

Moreover, “Brant, appearing from the outset to regard the [Grand River] territory as his own to manage on behalf of the Confederacy, interpreted the [Haldimand] proclamation as tantamount to full national recognition of the Mohawks and their fellow tribesmen” (Charles M. Johnston, ed. The Valley of the Six Nations, xxxviii-xxxix). His determination to sell off or lease (and sometimes give away) land to white settlers was based on this interpretation. While he eventually prevailed in this regard against British intransigence, it can be argued that his land dealings hardly led to a satisfactory result for the Six Nations in the long term.

There is no doubt that Brant is the central figure in the long and thorny relationship between the Six Nations and the Grand River. Without his early interventions, there would have been no relationship at all. The evidence indicates that Brant always acted with the welfare of his people in mind. Yet his legacy is profoundly contested, even among the Six Nations themselves.

Before we get to the third portrait, let’s deal with the result of Brant’s pressure on Haldimand.

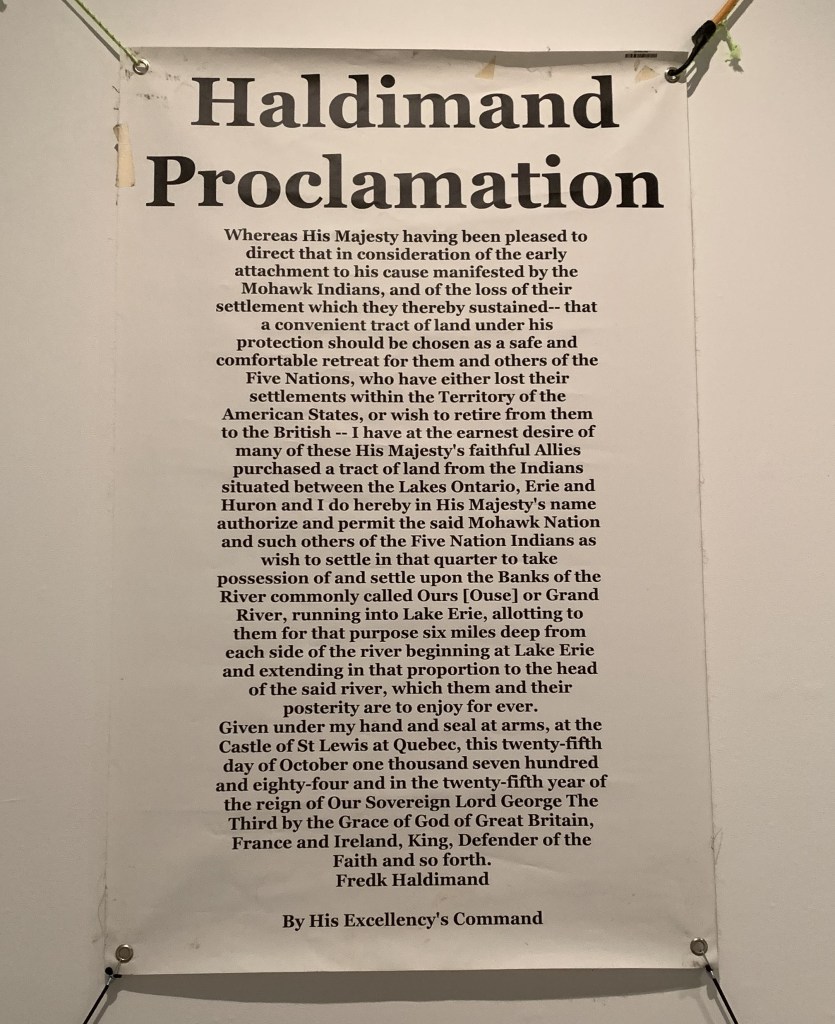

116. On 25 October 1784, Haldimand made the above Proclamation on behalf of the British Crown. It granted a considerable fraction of the land he had purchased to Brant’s Mohawks and their allies. It was practically Haldimand’s last action as Governor General, as he sailed for Britain in November and never returned to North America.

The wording would seem to be quite unambiguous: “I do hereby in His Majesty’s name authorize and permit the said Mohawk Nation and such others of the Five Nation Indians* as wish to settle in that quarter to take possession of and settle upon the Banks of the River commonly called Ours [Ouse] or Grand River, running into Lake Erie, allotting to them for that purpose six miles deep from each side of the river beginning at Lake Erie and extending in that proportion to the head of said river, which them and their posterity are to enjoy forever.”

It was a generous act, but one that very soon raised serious questions.

First, neither Haldimand nor Brant nor the Confederacy were familiar with the Grand River. While they knew it flowed into Lake Erie, they had no clue where its head was. The general ignorance is suggested by the wording, “beginning at Lake Erie,” implying that the Grand begins where it actually ends.

Second, a territory six miles either side of a river produces a serious demarcation problem. The Grand, like all rivers, meanders. Should the eastern and western boundaries of the allotted land meander in concert?

And third, the territory allotted was considerable, later estimated to be “about 674,910 acres,” i.e., 2,731 sq. km. But the Six Nations and their allies who first moved to the Grand River in 1785 had a combined population of only 1,843. Brant understood the Proclamation to record a gift of land in fee simple from one nation to another. He planned to sell off or lease what he considered superfluous portions to white settlers, creating a nest egg for future generations of his people. But the paternalistic British had other ideas. They insisted that the Six Nations had no right to sell any land without their approval. Meanwhile, some Six Nations members did not at all approve of Brant’s plan to sell their land to white settlers.

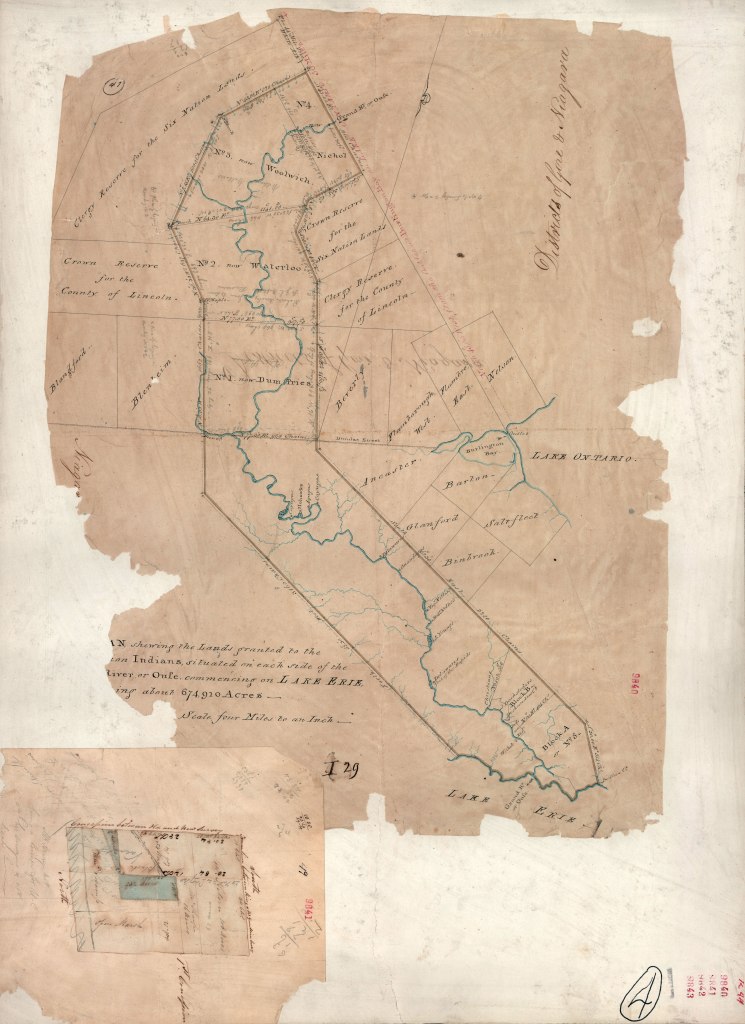

But what land were they arguing about? The Grand River had yet to be surveyed, boundaries marked, maps made, and signatures appended. (That a survey was not done before the Proclamation is only one of the unaccountable elements of this story.) The surveying job was given to this man …

*At the Confederacy’s foundation, there had been Five Nations; the Tuscarora joined somewhat later in 1722.

117. … Augustus Jones (ca. 1757-1836), born in rural New York State into a Loyalist family who left for the Niagara Peninsula in the early 1780s. Jones, a man of inexhaustible energy, did the earliest surveys of much of the Golden Horseshoe, including Dundas Street and Yonge Street, the first major highways in what is now southern Ontario.

In 1792 Jones was asked by John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, to survey the Grand River territory and establish precise boundaries of the tracts bought from the Mississaugas and granted to the Six Nations.

A baseline was drawn on a map extending 45 degrees from Burlington Bay along the eastern side of the territory purchased from the Mississaugas. According to the terms of the purchase, it was supposed to extend northwest as far as what is now the Thames River, but the northernmost source of that river is actually far to the west of the baseline. Jones, establishing the baseline on the ground, realized this error, caused by insufficient knowledge of geography by both parties. But then arriving near the source of the Conestogo River (near the present-day town of Arthur), Jones seemingly mistook it for the head of the Grand itself, and terminated his survey there.

Jones’s error, if such it was, was easily made. As we have seen, much of the Upper Grand is a mere creek, easily confused with other, lesser waterways. The result, however, was that the Six Nations never had title to the head of the Grand River, which as we know extends to Dundalk more than 50 km to the north, and lies outside the area of the 1784 purchase and its ratification as the Between the Lakes No. 3 Treaty.

Jones is a fascinating figure. He scandalized his times by fathering ten children by two wives, one Mississaugan and one Mohawk, spoke both his wives’ Native languages, employed Native assistants on his surveying trips, and was later in life a friend and neighbour of Joseph Brant on the Burlington Beach strip. In this way he served as an intermediary between two worlds that often failed to understand one another. For more information about his surveying, see Steve Thorning, “Augustus Jones and the Jones Baseline,” 53-60.

118. This would seem to be the earliest surviving map (1821) of the Haldimand Grant to the Six Nations. Its northern end is bounded by our Rubicon, the Jones Baseline. And the territory has been rationalized by being given straight edges in parallel 12 miles apart. Apparently an earlier map made by Jones in 1792 and signed off by the Six Nations leadership has been lost. Did the Six Nations agree to abandon their claim to the Upper Grand, and if so, why? A variety of answers offer themselves, but all are speculative. The Proclamation clearly grants Six Nations the land “to the head of said river,” and Joseph Brant, for one, refused to accept its curtailment. This issue remains unresolved today.

119. The present has its claims too, and Time and the Grand flow ever onwards. In future episodes I’ll continue to trace the repercussions of the Haldimand Proclamation. In the meantime, let’s leave the Grand at Fergus, just downstream from the bridge (#111 above) on the Jones Baseline. Old St. Andrews Mill is now a luxury condo development and what is marked at the top of the old map (#118 above) as “Falls 30 ft.” has probably been transformed over the years into the photogenic cascade here at the Wilson Dam. We’ll start the next episode near here.