66. Today’s hike from A to B is roughly 4.5 km from the Humber Bay Arch Bridge along, or in parallel to, a well-defined multiuse pathway as far as Exhibition Place, the vast complex that stages the annual Canadian National Exhibition (CNE). The course of the hike is marked with the usual red dots on the map above. It shouldn’t take you much more than an hour to walk it straight. However, there are a number of side trips of considerable interest, so you might set aside half a day if you want to cover all of them. There is ample (paid) parking at both ends, and there are streetcars along the Queensway and King Street West if you don’t want to have to walk in both directions.

67. The official name of the main trail from this point on the lakeshore eastward is the Martin Goodman Trail. The MGT runs 22 km from the Humber Arch Bridge to Balmy Beach, the latter of which will eventually be my terminus. Signs like the above – very infrequently provided – indicate that the MGT is suitable for jogging, wheelchairs, hiking and cycling. And it’s true that much of this section of the MGT is well paved, broad enough for two-directional use, and segregated from motor vehicles. You can even travel it on Google Street View. But it isn’t true that the MGT is suitable for jogging or hiking. Its chief hazard for people on foot – and it really is a hazard – are cyclists who feel that the MGT west of downtown is designed solely for them and pedestrians should stay out of their way or pay the price. These cyclists will approach you from behind without warning at great speed. Resistance is futile. The sheer number of them at most times of the day makes it dangerous to defy them. It’s much safer and pleasanter to take one of the parallel trails, like the Sunnyside Boardwalk, that are reserved solely for pedestrians.

The MGT commemorates Martin Wise Goodman (above left), editor-in-chief and later president of the Toronto Star, Canada’s largest newspaper, who died of cancer at the age of 46 in 1981. Goodman was known for his journalistic work towards national unity, for which he received the Order of Canada in the year of his premature death.

68. Our first stop is the imposing QEW Monument that stands in a clearing north of the trail. Its 12 metre column (top) is tall enough that, from the Humber Bridge, its crown can be seen poking above the surrounding trees even in summer.

Everyone in the Golden Horseshoe knows that QEW stands for Queen Elizabeth Way, the major highway between Toronto and Fort Erie on the US border. But the monarch referred to is not the one that most people assume. The Queen Elizabeth memorialized by the QEW was the long-lived wife – she died in 2002 aged 101 – of King George VI and the mother of Queen Elizabeth II (who died in 2022 at a mere 96). This Monument originally stood in the median at the Etobicoke end of the QEW when it was opened in 1937 as the first divided highway in North America. It was moved to this secluded location in 1974 after the QEW was widened.

The Monument was designed by William Lyon Somerville (1886-1965) in Art Deco style. He was the architect of most of the original buildings (in a very different Collegiate Gothic style) on the campus of McMaster University in Hamilton. Near the base of the column there is a circular medallion (bottom) with the profiles of Elizabeth and George in relief, and below that stands a lion (middle). It was sculpted in Queenston limestone by Frances Loring (1887-1968), the American-born pioneering female sculptor. The medallion and the upper crown were carved by her life partner Florence Wyle (1881-1968).

The inscription beneath the lion recalls the context of the monument’s dedication. King George and Queen Elizabeth visited Canada and the USA in May-June 1939, on the first ever visit by reigning British monarchs to those countries. The lion’s posture of aroused aggression was intended to represent the British Empire’s defiance as it prepared to confront Nazi Germany. For as WWII loomed, the royal visit took on a special significance, as the inscription under the lion, made in August 1940 after the war had begun, makes clear: “The courage and resolution of Their Majesties in undertaking the royal visit in face of imminent war have inspired the people of this province to complete this work in the Empire’s darkest hour in full confidence of victory and a lasting peace.”

69. Project Bookmark is an initiative designed to promote contemporary Canadian literature. It’s “a permanent series of site-specific literary exhibits using text from imagined stories that take place in real locations.” This Bookmark display board stands on the south side of the Sunnyside Boardwalk. On it you can read an intriguing passage set near this spot from the novel Love Enough (2014) by the Toronto poet and novelist Dionne Brand (b. 1953). You learn the anguished thoughts of a Toronto taxi driver originally from Somalia as he drops a woman who has a rendezvous with a dodgy-looking character at a parking lot off Lake Shore Boulevard West. On the Project Bookmark website there’s a photo of Dionne Brand standing by this Bookmark with the lakeshore behind her.

70. The Trans Canada Trail (TCT) was a brilliant idea hatched in 1992: a network of hiking trails 28,000 km long (bottom) that linked the whole country. The Toronto Waterfront Trail constitutes a tiny fragment of the 5,000 km of the TCT in Ontario. The TCT appealed for donations and got lots of them, both individual and corporate. The pavilion on the north side of the MGT (top) is filled with placards bearing the names of local donors.

Unfortunately, like many grand visionary schemes, the TCT fell short when it came to details. More than two thirds of the TCT is on roads shared with motorized vehicles, while other sections are on waterways requiring a canoe.

In 2016, the Trans Canada Trail was renamed the Great Trail (as this pavilion is branded), but the rebranding didn’t last long; the name reverted to the Trans Canada Trail in 2021. This U-turn suggested that there was some fumbling and stumbling going on backstage.

If there was, Diane Whelan was not deterred. On foot, by bicycle and boat, the 56-year-old filmmaker completed all 28,000 km of the TCT in 2021, taking six years to do so. Asked how she felt at the end of her epic trip, she said: “I was definitely crying, and it wasn’t because my journey was over. It was because of all the kindness of people. When you watch the news sometimes, you’re quite certain that the whole world’s full of sociopaths, and it’s not. I put myself in a very vulnerable position being out there alone for as long as I was. And I met a lot of people. And not once did I not meet kindness on my journey.”

For a further sample of the TCT, check out my photoblog on the 50 km section that runs along the Niagara River.

71. The QEW Monument stands at the western edge of Sir Casimir Gzowski Park. A little farther east, north of the MGT, is a monument to the park’s dedicatee. Gzowski (1813-98) was a Russian-born Polish engineer who moved to Canada in 1841 to work on the Welland Canal. He later became involved in railroad building, on works including the Grand Trunk Railroad from Toronto to Sarnia and the International Railway Bridge linking Fort Erie and Buffalo (opened 1873). One of his many other achievements was to serve as the first chairman of the Niagara Parks Commission. As I pointed out in my blog on the Niagara River Trail, “We … have him to thank that the Niagara riverbank is a long linear park, free to the public, and relatively unsullied by the tawdriness of central Niagara Falls.” Sir Casimir was the great-great-grandfather of the late CBC radio personality Peter Gzowski.

The rather ugly tripodal concrete pavilion (1968) contains now faded information about Gzowski’s many accomplishments, and contains a bronze bust of him (1896) by Frederick Turner Dunbar.

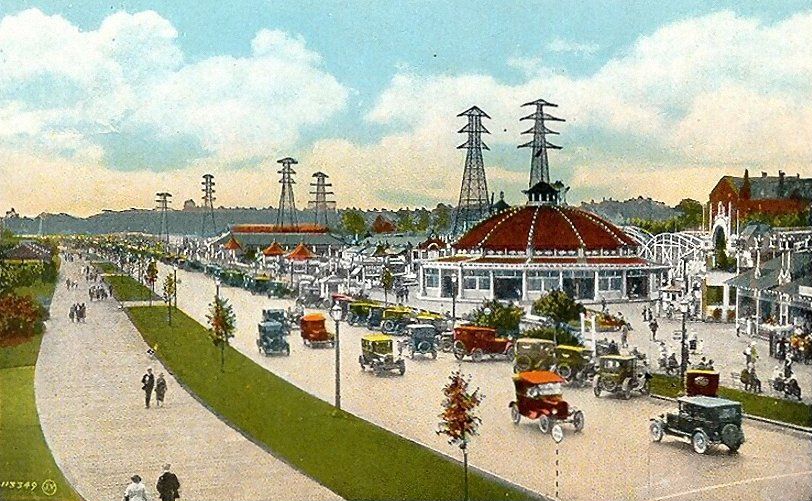

72. Next eastward on the trail are Sunnyside Park and Beach. They were created in a massive reclamation project during and after WWI. Breakwaters were built offshore and shallow areas infilled with dirt trucked in from Pickering and sand dredged from the bottom of the Lake. The transmission towers in the old photo above that once stood at the water’s edge soon found themselves a considerable way inland (see #73 below).

73. Sunnyside has definitely dwindled in importance over the years. This is how the lakeshore area between Parkside Drive and Roncesvalles Avenue looked in 1931. The depicted amusement park began operations in 1922, but was demolished in 1955 to make way for the Gardiner Expressway. Lakeshore Road, the predecessor of today’s Lake Shore Boulevard, cuts diagonally across the scene, and to its left is a broad wooden boardwalk.

74. The Sunnyside Beaches were rather popular back in the day, with the new Bathing Pavilion visible at left.

75. Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion as it is today. It was constructed in 1922 to provide change rooms for lake swimmers. Men changed in the west wing, women in the east. It held 7,700 lockers in all, and admission to the facility cost 25c. However, as Lake Ontario usually proved too cold to swim in, a large open air pool was built next to the Bathing Pavilion in 1925. “The Tank,” as the Sunnyside Outdoor Natatorium was commonly known, could hold up to 2,000 swimmers and at the time was the largest outdoor pool in the world. Sunnyside Pavilion is now a lakeside wedding venue and café. Sunnyside Gus Ryder Pool, the current name of the Outdoor Natatorium, is still operating, at least during the “season.” Gus Ryder was Marilyn Bell’s swimming coach (see #89 below).

76. A series of concrete breakwaters protect the beaches of Sunnyside from the often turbulent waters of the main Lake. Some stretches are often lined with cormorants …

77. … and in the lagoon formed by the breakwaters, I caught one of the cormorants in the act of swallowing a fish, headfirst and whole.

78. Today, a fine day in late September, the beaches of Sunnyside are thinly populated. As we shall see, that’s probably because this section of the waterfront is by no means easy to access …

79. … but this gentleman wearing headphones, catching a few rays, and sinking a cold one on this beach east of the Boulevard Club seems to be enjoying his solitude.

80. The next green space to the east is Budapest Park. This patched-up blue stegosaurus stands forlornly next to a paddling pool east of Sunnyside Gus Ryder Pool. It just couldn’t take the strain of having kids clambering all over it.

81. The Hungarian flag flies over the Freedom for Hungary Monument in Budapest Park. More than 37,500 refugees from the failed 1956 Hungarian Revolution against Soviet domination were accepted into Canada. Designed by the Hungarian-Canadian Victor Tolgesy (1928-80) and entitled “Freedom for Hungary – Freedom for All”, the Monument (1966) commemorated the 10th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution.

82. The Sunnyside Boardwalk, whose western end is near the Humber Arch Bridge and whose eastern end is here near the Palais Royale (a ballroom and wedding venue), is much pleasanter to walk along than the parallel MGT and its speeding cyclists. The original wooden boardwalk depicted in #73 above was replaced in the 1990s by one made of plastic planks, and is reserved for pedestrians only.

83. This is the trailside access near the Palais Royal to the bridge that takes pedestrians and cyclists more than 200 metres over Lake Shore Boulevard West, the Gardiner Expressway, and the GO Train tracks to the intersection of Queen St. West, King St. West, and Roncesvalles Ave. The Roncesvalles Pedestrian Bridge, as it’s called, was decorated (top) with colourful street art (2017) by Justus Roe as part of a cultural exchange between Toronto and Chicago. But Roe’s designs have now been partly overwritten and thoroughly disrespected by taggers (bottom).

Such a bridge is needed …

84. … as two extremely busy highways and train tracks divide this part of Toronto from the lakeshore. And that’s why pedestrian access to the Waterfront Trail and lakeshore around here is so limited.

Viewed from the Roncesvalles Pedestrian Bridge, a GO Train heads east toward Toronto’s Union Station on the Lakeshore West Line that here runs parallel to the Gardiner Expressway. GO Trains operate on seven commuter lines centred on the hub of Union Station. In some ways these trains are dinosaurs, conforming to a design six decades old. This one is comprised of 12 bi-level coaches each seating 162 passengers and pulled by a seriously polluting diesel locomotive.

Ridership on GO Trains was very low during the pandemic, but is now in vigorous recovery. GO Trains, however, though they have a theoretical top speed of 140 km/h, are painfully slow in practice compared to many of their European or Asian equivalents. This train’s 53 km journey from Aldershot to Union Station takes 70 mins, at an average speed of a little over 45 km/h. Time to start electrifying and upgrading the lines!

85. There’s another pedestrian bridge over the Gardiner Expressway and GO tracks at Dowling Avenue. Like much of the elevated section of the Gardiner itself, the concrete supports look in very rough shape. But even if you defy the dereliction and the speeding traffic below to cross the bridge from Parkdale, you still have to traverse at least six lanes of Lake Shore Boulevard at grade to get between the south end of this bridge and the MGT. So, getting to the lakeshore from the city on foot with a baby in a stroller or small child in tow is neither easy nor pleasant …

86. … and as an example of how difficult it is even for adult pedestrians to negotiate a passage between city and lakeshore, observe this young woman (centre) with the yellow bag risking her life to cross five eastbound lanes of Lake Shore Blvd.

87. This map shows clearly how the lakeshore west of Jameson Avenue is cut off from Parkdale by highways and rail lines. East of Jameson the Gardiner and the tracks leave the lakeshore and access becomes a bit easier, though now Exhibition Place has inserted itself between the city and its waterfront.

88. Given the challenges of getting to the waterfront on foot from Parkdale (the nearest west Toronto neighborhood), it’s perhaps not surprising that, aside from the cyclists speeding along the MGT, there’s hardly anyone else about. This is the next piece of greenery to the east, Marilyn Bell Park …

89. … named for the 16-year-old Toronto schoolgirl who performed a truly extraordinary physical feat: in 1954 she was the first person ever to swim across the 51.5 km width of Lake Ontario. The CNE had offered a $10,000 prize for a successful swim across the Lake to the American Florence Chadwick, famous for having recently swum across the English Channel in both directions in record time. Bell, who’d been offered no financial incentive, started her swim at the same time as Chadwick.

Marilyn Bell (b. 1937) began her epic lake crossing at Youngstown, NY at 11:07 pm on 8 September 1954. Chadwick gave up in exhaustion, but Bell swam on for just under 21 hours, ending at the breakwater across from the Boulevard Club. Though the direct route across the Lake was 51.5 km, Bell had to swim a greater distance thanks to waves, currents, primitive tracking equipment, and having to fend off blood-sucking lamprey eels. An enormous crowd greeted her as she arrived at 8:15 pm the next day. Popular sentiment demanded that CNE give Bell the prize intended for Chadwick. And so they did.

90. If one feature above all enlivens the often charmless Toronto urban landscape, it is the presence of striking street art. Here are three examples of decorated storage buildings in the linear parks along this stretch of the Waterfront Trail.

91. Here the MGT with its blue median stripe is segregated from a dedicated pedestrian way along the lakeshore. The view (bottom) is looking west from a bailey bridge (top) that gives pedestrians on the Waterfront Trail access to Exhibition Place. We are now at the eastern end of Humber Bay, and can estimate what distance we have covered from the distant skyline of the condos at Humber Bay Park. Let’s leave the waterfront to check out some interesting sites in Exhibition Place.

92. The Administration Building (1904), a.k.a. Press Building is the oldest building (aside from #97 below) on the Exhibition grounds, and the most appealing one. It’s in Beaux-Arts/Baroque Style and was designed by George Wallace Gouinlock (1861-1932). Love those fanciful details around the clock!

93. The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE), a.k.a. the Ex, runs annually at Exhibition Place for about 18 days, starting in mid-August and ending on Labour Day. It’s Canada’s largest fair and draws in about 1.5M attendees. The rest of the year the huge Exhibition grounds often seem semi-deserted, even though there are smaller exhibitions on offer. This one at the Better Living Centre is on the prog-rock band Pink Floyd, represented by this large inflatable pig.

94. More on the Origin of Toronto’s Name. This column marks a historic spot: the location of Fort Rouillé (established 1751). The blue plaque notes that the Fort “was established by order of the Marquis de La Jonquière, Governor of New France, to help strengthen French control of the Great Lakes and was located here near an important portage to capture the trade of Indians travelling southeast toward the British fur-trading centre at Oswego [now in New York State]. A small frontier post, Fort Rouillé was a palisaded fortification with four bastions and five main buildings. It apparently prospered until hostilities between the French and British increased in the mid-1750s. Following the capitulation of other French posts on Lake Ontario, Fort Rouillé was destroyed by its garrison in July 1759.” The plaque also notes that Fort Rouillé was “more commonly known as Fort Toronto.” However, the first Fort Toronto was a smaller French fort constructed in 1750 near the mouth of the Humber River. Fort Rouillé replaced it, but the alternative name “Toronto” was evidently transferred from the smaller to the larger fort that stood here. In 1834 it would be transferred again to the embryonic metropolis to the east of here.

95. The Shrine Peace Memorial in the rose garden in Exhibition Place. It was presented to the people of Canada in 1930 by the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. That’s the official name of the Shriners, the US-based Masonic brotherhood founded in 1870 whose costume and ritual draws on Middle Eastern themes. This has sometimes led the Shriners to be wrongly identified as a Muslim organization, whereas in fact their creation was fuelled by orientalism, that often patronizing western tendency to essentialize and imitate eastern culture and manners. Toronto hosted the Shriners’ annual Imperial Sessions as early as 1888 and as recently as 2010. The bronze statue “Angel of Peace” by Shriner sculptor Charles Keck (US, 1875-1951) is of an angel holding olive branches and supported by sphinxes. The legend around the base of the statue is PEACE BE ON YOU. ON YOU BE THE PEACE. The installation celebrates the long state of peace between the US and Canada. The fountain was added in 1958.

96. The Angel at the Shrine Peace Memorial may seem a bit kitschy to contemporary eyes, but compared to what’s on display in the rose garden a little to the east, it’s a masterpiece. The Garden of the Greek Gods is a collection of twenty sculptures representing characters from Greek mythology. These lumpen forms were hewn out of massive blocks of limestone. The three female figures (bottom) eyeing the Apple of Discord are Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, the trio of goddesses involved in that primal beauty contest, the Judgement of Paris. Needless to say, the Trojan Prince Paris awarded the Apple to Aphrodite, goddess of love and sex, and the Trojan War was the (indirect) result. As none of these three figures has a trace of beauty, grace, or desirability one might infer that the sculptor was either a satirist or a misogynist. Actually, the evidence of the other sculptures (top) would seem to indicate that he simply lacked a basic grasp of aesthetics. I won’t identify him, except to note that the display board refers to him as someone “widely acknowledged as Canada’s foremost sculptor in stone.” Really?

97. Toronto’s Oldest Building. Toronto was founded as the town of York in 1793. So, what’s its oldest building still standing? The answer is here in Exhibition Place: a log cabin built in 1794 by John Scadding, a government clerk from Devon, England. Scadding was a friend of lieutenant governor John Graves Simcoe, who had chosen York as the “temporary” capital of Upper Canada. The Scadding Cabin originally stood east of the Don River south of Queen Street East, and Scadding lived in it a mere two years before returning to the UK with Simcoe. Somehow the cabin survived, and was moved here in 1879 by the York Pioneers, an early historical society, to mark the founding of the Toronto Industrial Exhibition, ancestor of the CNE. The cabin is only open to visitors during the 18 days of the Ex.

And that’s where we’ll end this hike.